Minimizing Cardiovascular Risk in Bipolar Disorder

At the 2017 meeting of the American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, researcher Ben Goldstein gave an overview on cardiovascular risk and bipolar disorder. He noted a study by Nicole Kozloff and colleagues in the Journal of Affective Disorders in 2010 that indicated that onset of cardiovascular disorder occurred an average of 17 years earlier in those with BP I (at age 40-45 years) compared to controls (at age 55-60 years). Several risk factors made onset of cardiovascular disorder more likely, including diabetes, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome (which consists of any three of the five following symptoms: high cholesterol, triglycerides, blood sugar, blood pressure, and waist circumference).

At the 2017 meeting of the American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, researcher Ben Goldstein gave an overview on cardiovascular risk and bipolar disorder. He noted a study by Nicole Kozloff and colleagues in the Journal of Affective Disorders in 2010 that indicated that onset of cardiovascular disorder occurred an average of 17 years earlier in those with BP I (at age 40-45 years) compared to controls (at age 55-60 years). Several risk factors made onset of cardiovascular disorder more likely, including diabetes, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome (which consists of any three of the five following symptoms: high cholesterol, triglycerides, blood sugar, blood pressure, and waist circumference).

Risk factors include pathophysiological and behavioral mechanisms and certain medications. Pathophysiological mechanisms include inflammation, oxidative stress, and autonomic and endothelial dysfunction.

Behavioral mechanisms include poor diet, exercise, sleep, and increases in tobacco and alcohol use.

Medications could also contribute, with the most to least problematic for weight gain including, among atypical antipsychotics: clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone, and lurasidone. Among mood stabilizers, worst to best for avoiding weight gain are: valproate, lithium, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and lamotrigine.

Goldstein has data from retinal vascular photography (RVP), whereby blood vessels can be observed directly. As opposed to in adults, in youth large vessels are more problematic and arteriolar to venous ratio is abnormally higher in bipolar children compared to normal controls. This ratio is lower in bipolar adults, also reflecting increased cardiovascular risk.

Given the huge loss of life expectancy in bipolar disorder, primarily from cardiovascular disorders, Goldstein urges greater and earlier attention to reducing the pathophysiological, behavioral, and pharmacological mechanisms for poor health. These should be pursued in parallel with attempts at mood stabilization. Read more

An Inflammatory State Impedes Treatment for Bipolar Disorder

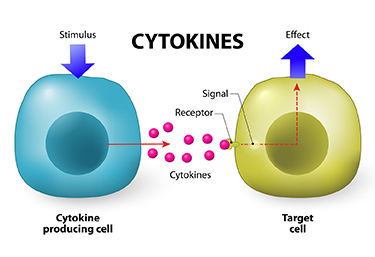

A 2017 study by in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry links inflammation to a poor antidepressant response in bipolar disorder. Many previous studies have found that elevated inflammatory markers are common in mood disorders, and that an inflammatory state seems to prevent response to certain therapies.

A 2017 study by in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry links inflammation to a poor antidepressant response in bipolar disorder. Many previous studies have found that elevated inflammatory markers are common in mood disorders, and that an inflammatory state seems to prevent response to certain therapies.

Researcher Francesco Benedetti and colleagues report that high levels of inflammatory cytokines (a type of small proteins) predicted a worse response to treatment with sleep deprivation and light therapy for bipolar depression. This treatment typically brings about a rapid antidepressant response.

Benedetti and colleagues measured 15 immune-regulating compounds in 37 patients who were experiencing an episode of bipolar depression and 24 healthy volunteers. Among those participants with bipolar disorder, 84% had a history of non-response to medication. Twenty-three of the 37 patients, or 62%, responded to the sleep deprivation/light therapy combination. Those who did not had higher levels of five cytokines: interleukin-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, interferon-gamma, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Body mass index was correlated with cytokine levels and also reduced response to the treatment.

The finding supports a link between the immune system and mood disorders. Evaluating a patient’s level of inflammation may, in the future, allow doctors to predict the patient’s response to a given therapy. Patients with high levels of inflammation might benefit most from treatments that target their immune system.

A Calculator of Risk for Bipolar Disorder in Youth

Daniella Hafeman of the University of Pittsburgh described a risk calculator for predicting an individual’s risk for bipolar disorder, which is available at www.pediatricbipolar.pitt.edu. Possible factors included in the risk calculation include a parent’s early age of onset of bipolar disorder, mood shifts early in life, a child’s anxiety or depression symptoms, later affective mood shifts, and new onset of subthreshold mania.

Editor’s Note: A “poor man’s” assessment of risk can also be of help to a family or clinician. There are four components. The first is genetic. Having one parent with bipolar disorder is a potent risk factor, and can be further magnified if the other parent also has a mood disorder. If three or more first degree relatives or three or more generations of first degree relatives have a mood disorder, this further increases risk four- to six-fold.

Perinatal vulnerability is another factor. Beyond these genetic vulnerabilities, a history of maternal toxoplasmosis or a viral infection during pregnancy, or the infant being noticeably underweight at birth can contribute to bipolar risk.

Childhood adversity also contributes to vulnerability to early onset of bipolar illness. A history of psychosocial stress in the child’s early years, such as abuse or abandonment, can be an added risk factor.

Prodromal or preliminary symptoms are also a risk factor. The development of an anxiety or depressive disorder, a disruptive behavioral disorder, or a bipolar not-otherwise-specified diagnosis (BP-NOS, used to describe manic symptoms of short duration) further increases risk. In studies by David Axelson and Boris Birmaher, 50% of children with an initial diagnosis of BP-NOS developed full-blown bipolar I or II illness upon several years of followup if there was a family history of bipolar disorder. About one-third converted to full bipolar disorder if there was no family history of bipolar disorder.

Thus, if a child has three or all four types of risk factors, their risk would be substantial. In this case, one might consider attempts at prevention. This could include a good diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids, regular exercise, joining a school sports team, developing good sleep habits, playing a musical instrument, and engaging in something akin to family focused therapy. Family focused therapy emphasizes psychoeducation, good communication skills, and problem solving. Attending to and treating parents’ symptoms and building a support system for both parents and the child can also help.

While these endeavors are not a guarantee to prevent the onset of more severe illness, they are all health-promoting in general and have few downsides.