Treatment Approaches to Childhood-Onset Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder

Dear readers interested in the treatment of young children with bipolar disorder and multiple other symptoms: In 2017, BNN Editor Robert M. Post and colleagues published an open access paper in the journal The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders titled “A Multi-Symptomatic Child: How to Track and Sequence Treatment.” The article describes a single case of childhood-onset bipolar disorder shared with us via our Child Network, a research program in which parents can create weekly ratings of their children’s mood and behavioral symptoms, and share the long-term results in graphic form with their children’s physicians.

Here we summarize potential treatment approaches for this child, which may be of use to other children with similar symptoms.

We present a 9-year-old girl whose symptoms of depression, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional behavior, and mania were rated on a weekly basis in the Child Network under a protocol approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. The girl, whose symptoms were rated consistently for almost one year, remained inadequately responsive to lithium, risperidone, and several other medications. We describe a range of other treatment options that could be introduced. The references for the suggestions are available in the full manuscript cited above, and many quotes from the original article are reprinted here directly.

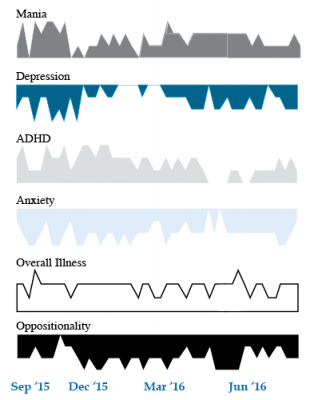

As illustrated in the figure below, after many weeks of severe mania, depression, and ADHD, the child initially appeared to improve with the introduction of 4,800 micrograms per day of lithium orotate (a more potent alternative to lithium carbonate that is marketed as a dietary supplement), in combination with 1 mg per day of guanfacine, and 1 mg per day of melatonin.

Despite continued treatment with lithium orotate (up to 9,800 micrograms twice per day), the patient’s oppositional behavior worsened during the period from November 2015 to March 2016, and moderate depression re-emerged in April 2016. Anxiety was also generally less severe from December 2015 to July 2016, and weekly ratings of overall illness remained in the moderate severity range (not illustrated).

In June 2016, the patient began taking risperidone (maximum dose 1.7 mg/day) instead of lithium, and her mania improved from moderate to mild. There was little change in her moderate but fluctuating depression ratings, but her ADHD symptoms got worse.

The patient had been previously diagnosed with bipolar II disorder and anxiety disorders including school phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Given the six weeks of moderate to severe mania that the patient experienced in October and November 2015, she would meet criteria for a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder.

Targeting Symptoms to Achieve Remission

General treatment goals would include: mood stabilization prior to use of ADHD medications, a drug regimen that maximizes tolerability and safety, targeting of residual symptoms with appropriate medications supplemented with nutraceuticals, recognition that complex combination treatment may be necessary, and combined use of medications, family education, and therapy.

Mood Stabilizers and Atypical Antipsychotics to Maximize Antimanic Effects

None of the treatment options in this section are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in children under 10 years of age, so all of the suggestions are “off label.” Further, they may differ from what other investigators in this area of medicine would suggest, especially since evidence-based medicine’s traditional gold standard of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials is impossible to apply here, given the lack of research in children with bipolar disorder.

As we share in the original article, reintroducing lithium alongside risperidone could be effective, as “combinations were more effective than monotherapy in a study [by] Geller et al. (2012), especially when they involved an atypical antipsychotic such as risperidone. This might include the switch from lithium orotate to lithium carbonate,” the typical treatment for bipolar disorder, on which more research has been done. “Combinations of lithium and valproate were also more effective than either [drug alone]…in the studies of Findling et al. (2006),” and many patients needed stimulants in addition.

“Most children also needed combinations of mood stabilizers (lithium, carbamazepine, valproate) in the study [by] Kowatch et al. (2000).” In a 2017 study by Berk et al. of patients hospitalized for a first mania, randomization to lithium for one year was more effective than quetiapine on almost all outcome measures.

Targeting ADHD

“[The increased] severity of [the child’s] ADHD despite improving mania speaks to the…utility of adding a stimulant to the regimen that already includes…guanfacine,” which is a common non-stimulant treatment for ADHD. “This would be supported by the data of Scheffer et al. (2005) that stimulant augmentation for residual ADHD symptoms does not [worsen] mania, and that the combination of a stimulant and guanfacine may have more favorable effects than stimulants alone.”

However, the consensus in the field is that mood stabilization should be achieved first, before low to moderate (but not high) doses of stimulants are added. “Thus, in the face of an inadequate response to the lithium-risperidone combination in this child, stimulants could be deferred until better mood stabilization was achieved.”

Other Approaches to Mood Stabilization and Anxiety Reduction

“The anticonvulsant mood stabilizers (carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproate) each have considerable mood stabilizing and anti-anxiety effects, at least in adults with bipolar disorder. With inadequate mood stabilization of this patient on lithium and risperidone, we would consider the further addition of lamotrigine.

Lamotrigine appears particularly effective in adults with bipolar disorder who have a personal history and a family history of anxiety (as opposed to mood disorders), and it has positive open data in adolescents with bipolar depression and in a controlled study of maintenance (in teenagers 13–17, but not in preteens 10–12) (Findling et al. 2015). With better mood stabilization, anxiety symptoms usually diminish…, and we would pursue these strategies [instead of using] antidepressants for depression and anxiety in young children with bipolar disorder.”

“Carbamazepine appears to be more effective in adults with bipolar who have [no] family history of mood disorders,” unlike lithium, which seems to work better in people who do have a family history of mood disorders.

“While the overall results of oxcarbazepine in childhood mania were negative, they did exceed placebo in the youngest patients (aged 7–12) as opposed to the older adolescents (13–18) (Wagner et al. 2006).

“There are long-acting preparations of both carbamazepine (Equetro) and oxcarbazepine (Oxtellar) that would allow for all nighttime dosing to help with sleep and reduce daytime side effects and sedation. Although data [on] anti-manic and antidepressant effects in adults are stronger for carbamazepine than oxcarbazepine,” there are good reasons to consider oxcarbazepine. First, there is the finding mentioned above that oxcarbazepine worked best in the youngest children. Second, there is a lower incidence of severe white count suppression on oxcarbazepine. Third, it has less of an effect on liver enzymes than carbamazepine. However, low blood sodium levels are more frequent on oxcarbazepine than carbamazepine.

Other Atypical Antipsychotics That May Improve Depression

“[In a study by Geller et al., the atypical antipsychotic] risperidone had more side effects than lithium or valproate, including more weight gain and prolactin elevations. These findings, along with the fact that risperidone is not FDA-approved for unipolar or bipolar depression in adults, suggests the possibility of switching this child to another atypical [antipsychotic] with better antidepressant and anti-anxiety effects.”

Lurasidone was recently approved for bipolar depression in young people aged 10–17 years old, and does not seem to cause much weight gain or other metabolic side effects.

Ziprasidone has anti-manic effects in adults and children, has the advantage of being relatively weight neutral, and recent data indicate its effectiveness as an adjunctive treatment in adults with mixed depression.

A widely used atypical antipsychotic, quetiapine, is approved for mania and bipolar depression in adults, but not in children. Weight gain on quetiapine is about equal to that of risperidone, but a study of quetiapine in young people with bipolar depression was not successful.

Aripiprazole, a dopamine partial agonist, is another atypical antipsychotic option. In children, weight gain on aripiprazole can range from minimal to substantial, and aripiprazole decreases the hormone prolactin. While aripiprazole failed to show efficacy in bipolar depression in adults, it is FDA-approved for use alongside antidepressants for unipolar depression.

Two new drugs that are also dopamine partial agonists may be of some use. Brexpiprazole was recently approved by the FDA for adults with schizophrenia and as an adjunct to antidepressants in unipolar depression. Cariprazine is FDA-approved for adults with schizophrenia and mania, was superior to placebo in three studies of bipolar depression, and has been successful as an adjunctive treatment for unipolar depression.

Olanzapine and clozapine are less appealing options because they cause more weight gain than most other atypical antipsychotics, and clozapine also requires weekly monitoring of white blood cell count. However, among atypical antipsychotics clozapine has the highest rate of anti-manic response in adults, and has been used successfully in childhood-onset schizophrenia.

It is clear that comparative studies of the efficacy and tolerability of atypical antipsychotics in children with bipolar disorder are sorely needed.

In a patient like the one we’ve discussed, if an excellent mood and anxiety response is achieved using mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics, but substantial residual symptoms of ADHD and oppositional behavior remain, a stimulant could then be added, as noted above.

Nutraceutical Approaches to Depression, Anxiety, and Oppositional Behavior

For children like the one in our case study, who have shown some improvement but still have residual symptoms, we would add a series of adjunctive treatments to the combination of an atypical antipsychotic, lithium, and another mood stabilizer.

An excellent option for residual anxiety and depression is N-acetylcysteine (NAC). In studies in adults, this antioxidant has performed better than placebo at reducing bipolar depression, and it can also improve the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (SSRIs) in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). It can also improve a variety of habit-based behaviors such as addictions.

In children with autism, three placebo-controlled studies found that NAC reduced irritability. (One study looked at NAC by itself, and the other two used the supplement as an adjunct to risperidone.) NAC is sold without a prescription in health food stores, and doses of 500mg twice per day can slowly be increased (on a weekly basis) to 2,000–2,700mg/day.

There is some support for the use of omega-3 fatty acids to target depression and ADHD, and their safety suggests there is little risk in trying them for patients who have symptoms of both.

Many children with serious psychiatric illness have deficiencies in vitamin D3, and open data in 6–17-year-old patients with bipolar disorder suggests that taking vitamn D3 supplements can improve symptoms.

In children who have undergone genetic testing that identified a methyl-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) deficiency, supplementation with l-methylfolate should be used (rather than folate itself) and could also improve depression, as it seems to in adults (when taken alongside SSRIs).

For children with oppositional behavior that persists despite multiple attempts at mood stabilization and stimulant augmentation, there are complex combinations of vitamins and minerals that may have some effect. EMPowerplus is one branded supplement designed to support children’s mental health that has been found to be safe and effective in small open trials with children with bipolar disorder and behavioral dyscontrol. It may have some interactions with other drugs, especially lithium, doses of which would need to be reduced.

Psychotherapeutic approaches

There are several psychotherapeutic approaches that can help children manage their illness, particularly those that involve the family as a whole and focus on illness education, improved communication, mood and behavioral charting, cognitive behavioral therapy, problem solving, and alternatives to punitive discipline. Family-focused therapy, an approach developed by researcher David Miklowitz and colleagues, is one good option.

It may be difficult to find a therapist trained in such techniques, but the efforts are likely worthwhile. Research by Lars Kessing has shown that patients hospitalized for the first time with mania who were randomized to two years of treatment at a specialty clinic fared better than those who received treatment as usual. They had fewer relapses and did better even years after the specialty treatment ended, suggesting that a good initial intervention that includes education may improve the long-term course of illness.

Researcher Lakshmi Latham and colleagues have found that that cognition returns to normal after a first manic episode only if there are no recurrences over the following year, suggesting the importance of initiating intensive treatment that incorporates both medication and therapy aimed at prevention after a first manic episode.

Mood Charting

Since systematic treatment data in children are so lacking, the best guidance for treatment is the individual child’s actual response. Charting the child’s improvement or deterioration after trying a given treatment can facilitate parental and clinical decision-making.

We thus encourage parents to provide this type of input and feedback to physicians in a format such as the one used in our Child Network.