Intranasal Ketamine for Bipolar Disorder

An in-press article due out in January 2018 by Demitri F. Papolos and colleagues in the Journal of Affective Disorders reports that intranasal ketamine delivered every three to four days reduced symptoms of bipolar disorder in 45 teens (aged 16 years on average). The teens treated in one private practice had the ‘fear-of-harm’ subtype, which in addition to bipolar symptoms is characterized by treatment resistance, separation anxiety, aggressive obsessions, disordered sleep, and poor temperature regulation.

An in-press article due out in January 2018 by Demitri F. Papolos and colleagues in the Journal of Affective Disorders reports that intranasal ketamine delivered every three to four days reduced symptoms of bipolar disorder in 45 teens (aged 16 years on average). The teens treated in one private practice had the ‘fear-of-harm’ subtype, which in addition to bipolar symptoms is characterized by treatment resistance, separation anxiety, aggressive obsessions, disordered sleep, and poor temperature regulation.

The repeated administration of ketamine produced long-lasting positive results, improving bipolar symptoms as well as social function and academic performance. Many participants reported via survey that they were much or very much improved after being treated for durations ranging from 3 months to 6.5 years. Side effects were minimal and included sensory problems, urination problems, torso acne, dizziness, and wobbly gait.

The ketamine was delivered to alternating nostrils via 0.1 ml sprays that included 50–200 mg/ml of ketamine in 0.01% benzalkonium chloride. Patients were instructed to increase the dosage just up until it became intolerable and then repeat the last tolerable dose every three to four days. Final doses ranged from 20–360 mg. The mean dose was 165 mg (plus or minus 75 mg) delivered every 3 days.

Papolos and colleagues called for placebo-controlled clinical trials based on the positive results from this open study.

An Overview of Ketamine for Treatment-Resistant Depression

A 2017 series of articles by researcher Chittaranjan Andrade in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry reviews the last 10 years of research on ketamine, the anesthetic drug that in smaller doses (0.5 mg/kg of body weight) can bring about rapid antidepressant effects. Ketamine is typically delivered intravenously (though it can also be delivered via inhaler, injected under the skin or into muscles, and least effectively by mouth). Ketamine can improve depression in less than an hour, but its effects usually fade within 3 to 5 days. Repeating infusions every few days can extend ketamine’s efficacy for weeks or months.

A 2017 series of articles by researcher Chittaranjan Andrade in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry reviews the last 10 years of research on ketamine, the anesthetic drug that in smaller doses (0.5 mg/kg of body weight) can bring about rapid antidepressant effects. Ketamine is typically delivered intravenously (though it can also be delivered via inhaler, injected under the skin or into muscles, and least effectively by mouth). Ketamine can improve depression in less than an hour, but its effects usually fade within 3 to 5 days. Repeating infusions every few days can extend ketamine’s efficacy for weeks or months.

Andrade cited a 2016 meta-analysis of nine ketamine studies by T. Kishimoto and colleagues in the journal Psychological Research. The meta-analysis found that compared to placebo, ketamine improved depression beginning 40 minutes after IV administration. Its effects peaked at day 1 and were gone 10–12 days later. Remission rates were better than placebo starting after 80 minutes and lasting 3–5 days.

Several studies have found that ketamine also reduces suicidality.

Andrade reported that both effectiveness and side effects seem to be dose-dependent within a range from 0.1 mg/kg to 0.75 mg/kg.

Side effects of ketamine are typically mild and transient. A 2015 study by Le-Ben Wan and colleagues (also in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry) that Andrade cited reported that in 205 sessions of ketamine administration, the most common side effects were drowsiness, dizziness, poor coordination, blurred vision, and feelings of strangeness or unreality. The feelings of unreality (dissociative effects) diminish with repeated infusions. Heart and blood pressure may also temporarily increase as a result of ketamine administration.

One study found that ketamine could speed up and add to the effects of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant escitalopram (Lexapro). A meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials found that ketamine did not improve the effects of electroconvulsive therapy.

Ketamine has some history as a recreational club drug (sometimes known as ‘K’ or ‘special K’), and can be misused or abused.

While there have been many studies of ketamine’s antidepressant effects, Andrade concludes that none is of a standard to justify US Food and Drug Administration approval for the drug. It is hoped that larger, more rigorous trials will be completed in the next few years. However, ketamine is already being used widely to treat treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression.

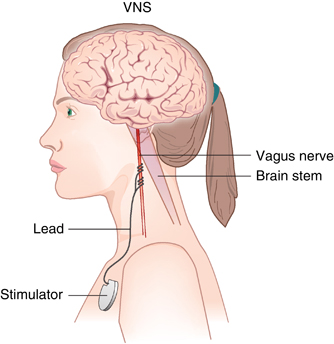

Vagus Nerve Stimulation Improves Depression When Other Treatments Fail

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression since 2005. The treatment consists of a pacemaker-like device implanted under the skin in the chest that delivers regular, mild electrical pulses to the brain via the left vagus nerve.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression since 2005. The treatment consists of a pacemaker-like device implanted under the skin in the chest that delivers regular, mild electrical pulses to the brain via the left vagus nerve.

A 2017 study by Scott T. Aaronson and colleagues in the American Journal of Psychiatry reports that over a 5-year period, people with treatment-resistant depression who received VNS did better than those who received treatment as usual. The 795 participants at 61 US sites had either a depressive episode that had lasted for at least two years or had had three or more depressive episodes and had failed to respond to at least four treatments, including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Over five years, those who received VNS had higher response rates (67.6% versus 40.9%) and higher remission rates (43.3% versus 25.7%) compared to those who received treatment as usual.

While the study by Aaronson and colleagues was non-blind and non-randomized, it suggests that VNS could be helpful in the long-term management of treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression.

Editor’s Note: VNS was FDA-approved for treatment-resistant seizures in patients aged 12 and older in 1997 and for children 4 years and older in 2017. It was also approved for cluster headaches in 2017. Insurance coverage and reimbursement for VNS is typically available for these neurological conditions, but not for the treatment of depression. This is an unfortunate example of the stigmatization of psychiatric illness—when an FDA-approved device can be kept from people in need of treatment.

One Night of Sleep Deprivation Can Rapidly Improve Depression

One night of sleep deprivation can bring about rapid improvement in depression symptoms the following day. A 2017 meta-analysis by Elaine M. Boland and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry summarizes the findings from 66 studies of sleep deprivation for unipolar and bipolar depression and finds that the technique produced a response rate of 45% in randomized controlled studies.

One night of sleep deprivation can bring about rapid improvement in depression symptoms the following day. A 2017 meta-analysis by Elaine M. Boland and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry summarizes the findings from 66 studies of sleep deprivation for unipolar and bipolar depression and finds that the technique produced a response rate of 45% in randomized controlled studies.

It did not seem to matter whether patients experienced full or partial sleep deprivation, whether they had unipolar or bipolar depression, or whether or not they were taking medication at the time. Age and gender also did not affect the results of the sleep deprivation.

Extending the Effects

While sleep deprivation can rapidly improve depression, the patient often relapses after the next full night of sleep. There are a few things that can prevent relapse or extend the efficacy of the sleep deprivation. The first is lithium, which has extended the antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation in people with bipolar disorder.

The second strategy to prevent relapse is a phase change. This means going to sleep early in the evening the day after sleep deprivation and gradually shifting the sleep schedule back to normal. For example, after an effective night of sleep deprivation, one might go to sleep at 6pm and set their alarm for 2am. Then the next night, they would aim to sleep from 7pm to 3am, the following night 8pm to 4am, etc. until the sleep wake cycle returns to a normal schedule.

A 2002 article by P. Eichhammer and colleagues in the journal Life Sciences suggested that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), electromagnetic stimulation of the scalp over the prefrontal cortex, could help maintain improvement in depression following a night of partial sleep deprivation for up to four days.

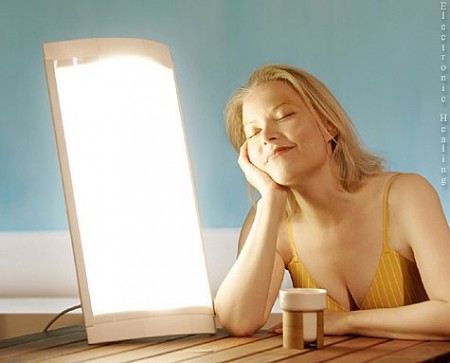

Bright light therapy may also help. Read more

Inflammation Predicts Poor Response to Sleep Deprivation with Light Therapy

A 2017 article by Francesco Benedetti and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry reports that people with bipolar depression who have higher levels of certain inflammatory markers may have a poor antidepressant response to the combination of sleep deprivation and light therapy, compared to those with lower levels of inflammation.

The study included 37 participants with bipolar disorder who were in the midst of a major depressive episode. Of those, 31 participants (84%) had a history of poor response to antidepressant medication. The patients were treated with three cycles of total sleep deprivation and light therapy within one week, a combination that can often bring about a rapid improvement in depression.

Depression improved in a total of 23 patients (62%) following the therapy. Blood analysis showed that compared to those who had a good response, the non-responders had higher levels of five intercorrelated inflammatory markers: IL-8, MCP-1, IFN-gamma, IL-6, and TNF-alpha. Those with higher body mass index had more inflammation, indirectly decreasing response to the therapy.

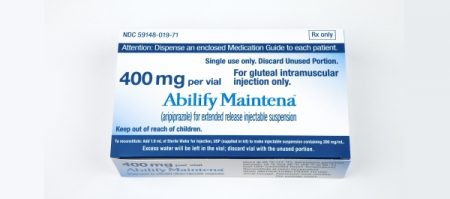

FDA Approves Extended-Release Aripiprazole Injected Monthly to Prevent Manic and Mixed Episodes in Bipolar I

In 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration approved a monthly injectable form of the atypical antipsychotic drug aripiprazole, Abilify Maintena, for the prevention of manic and mixed episodes in bipolar I disorder. The intramuscular injections are available for monotherapy in preparations of 300 mg or 400 mg. Maintena did not prevent depressive episodes.

Maintena is already FDA-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia and Tourette’s syndrome in adults.

The approval for bipolar I disorder follows a 52-week phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Participants were experiencing a manic episode during screening for the study, met the criteria for bipolar I disorder, and had had at least one prior manic or mixed episode severe enough to require treatment.

Compared to placebo, Maintena in once-a-month injections delayed the recurrence of any mood episode following the initial manic episode at screening. When the researchers separated their analysis based on type of episode, Maintena reduced manic and mixed episodes compared to placebo, but did not do a better job than placebo at preventing depressive episodes.

An oral antipsychotic must be administered for 14 days following the first injection of Maintena. The extended-release injection is available as 300 mg– or 400 mg–strength powder that may be reconstituted, or as prefilled syringes.

Editor’s Note: Because Maintena is delivered as a once-a-month injection, it may be helpful for patients who struggle to take daily oral medications.

Midday Bright Light Therapy Improved Bipolar Depression

A study by Dorothy K. Sit and colleagues published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2017 found that delivering bright white light therapy to patients with bipolar depression between the hours of noon and 2:30pm improved their depression compared to delivering inactive dim light, and did not cause mood switches into mania. The study included 46 patients with moderate bipolar depression, no hypomania and no psychosis.

The active therapy group was exposed to broad-spectrum bright white fluorescent light at 7,000 Lux while the inactive group received dim red light at 50 Lux. Both groups were instructed to sit 12 inches from the light and face it without looking directly at it. The therapy began with 15-minute afternoon sessions and increased to 60 minutes per day by 4 weeks. Participants were assessed weekly. Remission rates increased dramatically in the active group beginning in the fourth week. At weeks 4 through 6, the remission rate for those in the active bright light group was 68.2% compared to only 22.2% in the dim light group.

Mean depression scores were better in the treated group, as were global functioning and response rates.

Some participants were taking antidepressants concurrently, and these participants were evenly distributed across the two study groups.

An earlier pilot study by the same researchers had found that bright light therapy delivered in the morning was followed by some hypomanic reactions or bipolar cycling. The midday sessions did not cause any mood switching.

Bright light therapy is often used to treat seasonal affective disorder (SAD) using a 10,000 Lux light box. This study took place mostly during the fall and winter months.

Editor’s Note: Bright light therapy is generally safe and boasts a high remission rate. Light boxes can be acquired without a prescription and are portable and easy to use. Midday light may have the best results and the least risk of provoking a mood switch into mania.

Study Suggests Magnesium Could Improve Mild to Moderate Depression as Much as SSRIs

Researcher Emily Tarleton and colleagues report in a 2017 article in the journal PLoS One that over-the-counter magnesium may improve mild to moderate unipolar depression with efficacy similar to that of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants. Magnesium is a mineral that can fight inflammation.

The 126 participants in the open study had an average age of 52. Compared to not taking magnesium, taking 248 mg/day of magnesium produced statistically significant improvement in depression and anxiety symptoms after only two weeks.

The magnesium was well-tolerated by participants. Tarleton and colleagues hope to replicate their findings with a larger and more diverse population.

Making Lithium Treatment More Tolerable For Patients

In a slideshow at Psychiatric Times, Chris Aiken describes seven ways to improve lithium’s tolerability. Since many researchers, including BNN Editor-in-Chief Robert M. Post, have suggested that lithium should be used more often as a treatment for bipolar disorder, ways of making its side effects more manageable are of great interest. Here we summarize Dr. Aiken’s seven points and add a few perspectives of our own.

In a slideshow at Psychiatric Times, Chris Aiken describes seven ways to improve lithium’s tolerability. Since many researchers, including BNN Editor-in-Chief Robert M. Post, have suggested that lithium should be used more often as a treatment for bipolar disorder, ways of making its side effects more manageable are of great interest. Here we summarize Dr. Aiken’s seven points and add a few perspectives of our own.

Aiken writes that “when it comes to the side effects that matter most to patients—sedation, weight gain, and cognition—lithium’s tolerability ranks right behind lamotrigine.” In fact, lithium plus lamotrigine is an excellent combination, as lithium excels at preventing manias while lamotrigine excels at depression prevention.

Post’s philosophy is that many of lithium’s side effects can be avoided in the first place through judicious dose titration. He suggests gradually increasing dosage, and stopping before side effects become difficult, or reducing a dosage that has already become a problem. The idea is to avoid lithium side effects even if blood levels of lithium remain below clinically therapeutic levels. Post suggests using lithium at whatever dose is not associated with side effects.

Many of lithium’s positive therapeutic effects emerge at low doses, and if this improvement is insufficient, the rest of the needed efficacy can be achieved by adding other medications. As noted above, lamotrigine is a good option for break-through depression, as is lurasidone. For breakthrough mania, the mood stabilizers valproate and carbamazepine or an atypical antipsychotic can be added to lithium.

A little-appreciated option for enhancing lithium’s mood stabilizing effects is nimodipine, a dihydropyridine calcium blocker. It has both antimanic and antidepressant efficacy without lithium’s side effects. Research showed that a year on the combination of lithium and nimodipine was more effective than a year of either drug alone.

If a patient taking lithium experiences a tremor at a dose that is not fully effective, nimodipine can be added in order to lower the lithium dose enough to eliminate the tremor.

Nimodipine specifically blocks the calcium influx gene CACNA1C that has been repeatedly been associated with the vulnerability to bipolar disorder and depression.

If side effects do occur on lithium, they can often be managed. The following suggestions are adapted from Aiken’s article with input from Post. Read more

The New News About Lithium

Robert M. Post, Editor-in-Chief of the BNN, recently published an open access article in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, “The New News About Lithium: An Underutilized Treatment in the United States.” Here we summarize the main points of the publication, including: the multiple benefits of lithium, its relative safety, predictors of lithium responsiveness, and principles for treatment.

Benefits of lithium

Lithium prevents both depressions and manias in bipolar disorder, and also prevents depressions in unipolar disorder and can augment antidepressant effects acutely. In addition to these mood benefits, lithium has anti-suicide effects. Lithium also enhances the efficacy of atypical antipsychotics and other mood stabilizers when used in combination with them.

Lithium is good for the brain. It has been shown to reduce the incidence of dementia. Lithium increases the volume of the hippocampus and cortex, and can increase the production of new neurons and glia. It also protects neurons. In animals, lithium has been shown to reduce lesion size in neurological syndromes that are models for human disorders such as AIDS-related neurotoxicity, ischemic/hemorrhagic stroke, traumatic brain/spinal cord injury, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease), fragile X syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, retinal degeneration, multiple sclerosis, alcohol-induced degeneration, Down’s syndrome, spinocerebellar ataxia-1, and irradiation.

Lithium’s benefits include more general ones as well. It can increase the length of telomeres, bits of DNA on the ends of chromosomes that protect them during replication. Short telomeres have been linked to various illnesses and the aging process. Lithium also decreases the incidence of several medical illnesses and enhances survival.

Side Effects Are Often Benign, Treatable

Lithium side effects are more benign than many people think. Even low levels of lithium may be therapeutically sufficient. Read more