Participation in Sports May Mitigate Genetic Risk for ADHD in School-Aged Children

At the 2021 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, researcher Keiko Kunitoki and colleagues reported that participation in sports decreased behavior abnormalities in 9- and 10-year-old children at genetic risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Sports were associated with greater hippocampal volume, which was associated with fewer behavioral abnormalities. Kunitoki and colleagues concluded that “participation in team sports mitigated genomic risk for psychopathology at age 9–10 in part through increased hippocampal volume.”

Editor’s Note: These data are consistent with a program called the Vermont Family-Based Approach developed by researcher James Hudziak, who heads the Vermont Center for Children, Youth and Families at the University of Vermont. The program encourages families to practice different domains of wellness, such as music, mindfulness, exercise, and nutrition, among others. The idea is to support emotional and behavioral health, and to do so intensively in families where children show signs of mood and behavioral difficulties or are at risk for these difficulties.

Hudziak analyzed brain scans of 232 children aged 6 to 18 and reported that “practicing an instrument such as the piano or violin increased working memory, gray matter volume in the brain, and the ability to screen out irrelevant noise. Practicing mindfulness increased white matter volume and reduced anxiety and depression. Exercise also increased brain volume and neuropsychological abilities.”

In 2015, researcher Benjamin I. Goldstein reported that 20 minutes of vigorous exercise on a bike improved cognition and decreased hyperactivity in the medial prefrontal cortex in adolescents with and without bipolar disorder, and researcher Danella M. Hafeman reported that offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who exercised more had lower levels of anxiety.

To summarize, engaging in exercise, team sports, music, and meditation/mindfulness are beneficial for all children, and can be especially helpful for those at risk for depression or bipolar disorder. Children who are already symptomatic should additionally be offered something like family focused therapy (FFT), a multi-faceted approach developed by researcher David Miklowitz, in which families of young people at risk for bipolar disorder take part in therapy, learning together about the illness and practicing strategies for communication and coping.

ADHD Common in People with Mood Disorders

In a meta-analysis published in the journal Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica in 2021, researcher Andrea Sandstrom and colleagues reported that people with mood disorders had a three times higher incidence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than people without mood disorders. ADHD was also more likely to occur in people with bipolar disorder than in people with major depression. The comorbidity is most common in childhood, less so in adolescence, and lowest in adulthood.

Based on 92 studies including a total of 17,089 individuals, the prevalence of ADHD in people with bipolar disorder is 73% in childhood, 43% in adolescence, and 17% in adulthood. Data from 52 studies with 16,897 individuals indicated that prevalence of ADHD in major depressive disorder is 28% in childhood, 17% in adolescence, and 7% in adulthood.

Editor’s Note: A key implication of this research is that there is a huge overlap of bipolar disorder and ADHD in childhood, and that physicians need to specifically look for bipolar symptoms that are not common in ADHD to make a correct diagnosis. These include: brief or extended periods of mood elevation and decreased need for sleep in the youngest children; suicidal or homicidal thoughts and threats in slightly older children; hyper-sexual interests and actions; and hallucinations and delusions. When these are present, even when there are also clear-cut ADHD symptoms, a clinician must consider a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and treat the child with mood stabilizers prior to using stimulants or other traditional ADHD medications.

Conversely, physicians should be aware of the much lower incidence of ADHD in adolescents and adults with bipolar disorder. Here one should first make sure that the apparent ADHD symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, poor concentration, etc. do not result from inadequately treated mania and depression, and if they do, treat these symptoms to remission prior to using traditional ADHD medications.

Study Examines Comorbidity of ADHD and Bipolar Disorder

In a 2021 review and meta-analysis in the journal Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, researcher Carmen Schiweck and colleagues described the comorbidity of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and bipolar disorder in adults. This was the first review and meta-analysis to quantify the comorbidity of the two fairly prevalent disorders. The meta-analysis included 71 studies with a combined total of 646,766 participants from 18 countries.

The review found that among people with ADHD, about 1 in 13 also have bipolar disorder, while among people with bipolar disorder, 1 in 6 have comorbid ADHD. The prevalence differed depending on the continent where patients lived and the diagnostic systems used there, with greater prevalence of both disorders in the US, where the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is used, than in Europe, where the International Classification of Diseases is typically used. (Other parts of the world were less represented in the meta-analysis.) Schiweck and colleagues found that bipolar disorder had an onset about 4 years earlier in patients who had comorbid ADHD.

Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders Impair Response to Psychosocial Treatment in Adolescents with Bipolar Disorder

At the 2019 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, researcher Marc J. Weintraub and colleagues followed 145 adolescents with bipolar disorder over a period of two years. The adolescents with comorbid disorders (compared to those with bipolar disorder alone) fared more poorly in response to psychosocial treatment.

Weintraub and colleagues found that the adolescents who had anxiety disorders in addition to their bipolar disorder spent more weeks depressed, had more severe symptoms of (hypo)mania, and had more family conflict over the course of the study than those adolescents who had bipolar disorder alone.

Participants who had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in addition to their bipolar disorder had more weeks with (hypo)manic symptoms, had more severe (hypo)manic symptoms, and greater family conflict than those with bipolar disorder alone.

Those participants with comorbid oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conflict disorder in addition to their bipolar disorder had more depressive symptoms and family conflict throughout the study.

Editor’s Note: How to better approach treatment in these diagnostically complex young people is an urgent unmet need, as most research excludes participants with more than one psychiatric disorder. Clinicians treating young people with bipolar disorder and comorbidities such as anxiety disorder, ADHD, and ODD must generally rely on inferences from children with these illnesses, using their own intuition about best treatment approaches rather than having evidence from systematic studies about how best to treat these children. It appears that both psychosocial and pharmacological treatments must be tailored to these more complicated presentations.

Treatment Approaches to Childhood-Onset Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder

Dear readers interested in the treatment of young children with bipolar disorder and multiple other symptoms: In 2017, BNN Editor Robert M. Post and colleagues published an open access paper in the journal The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders titled “A Multi-Symptomatic Child: How to Track and Sequence Treatment.” The article describes a single case of childhood-onset bipolar disorder shared with us via our Child Network, a research program in which parents can create weekly ratings of their children’s mood and behavioral symptoms, and share the long-term results in graphic form with their children’s physicians.

Here we summarize potential treatment approaches for this child, which may be of use to other children with similar symptoms.

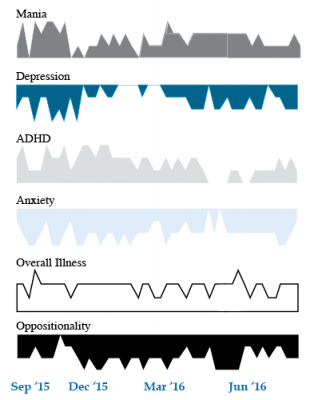

We present a 9-year-old girl whose symptoms of depression, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional behavior, and mania were rated on a weekly basis in the Child Network under a protocol approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. The girl, whose symptoms were rated consistently for almost one year, remained inadequately responsive to lithium, risperidone, and several other medications. We describe a range of other treatment options that could be introduced. The references for the suggestions are available in the full manuscript cited above, and many quotes from the original article are reprinted here directly.

As illustrated in the figure below, after many weeks of severe mania, depression, and ADHD, the child initially appeared to improve with the introduction of 4,800 micrograms per day of lithium orotate (a more potent alternative to lithium carbonate that is marketed as a dietary supplement), in combination with 1 mg per day of guanfacine, and 1 mg per day of melatonin.

Despite continued treatment with lithium orotate (up to 9,800 micrograms twice per day), the patient’s oppositional behavior worsened during the period from November 2015 to March 2016, and moderate depression re-emerged in April 2016. Anxiety was also generally less severe from December 2015 to July 2016, and weekly ratings of overall illness remained in the moderate severity range (not illustrated).

In June 2016, the patient began taking risperidone (maximum dose 1.7 mg/day) instead of lithium, and her mania improved from moderate to mild. There was little change in her moderate but fluctuating depression ratings, but her ADHD symptoms got worse.

The patient had been previously diagnosed with bipolar II disorder and anxiety disorders including school phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Given the six weeks of moderate to severe mania that the patient experienced in October and November 2015, she would meet criteria for a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder.

Targeting Symptoms to Achieve Remission

General treatment goals would include: mood stabilization prior to use of ADHD medications, a drug regimen that maximizes tolerability and safety, targeting of residual symptoms with appropriate medications supplemented with nutraceuticals, recognition that complex combination treatment may be necessary, and combined use of medications, family education, and therapy.

Mood Stabilizers and Atypical Antipsychotics to Maximize Antimanic Effects

None of the treatment options in this section are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in children under 10 years of age, so all of the suggestions are “off label.” Further, they may differ from what other investigators in this area of medicine would suggest, especially since evidence-based medicine’s traditional gold standard of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials is impossible to apply here, given the lack of research in children with bipolar disorder.

As we share in the original article, reintroducing lithium alongside risperidone could be effective, as “combinations were more effective than monotherapy in a study [by] Geller et al. (2012), especially when they involved an atypical antipsychotic such as risperidone. This might include the switch from lithium orotate to lithium carbonate,” the typical treatment for bipolar disorder, on which more research has been done. “Combinations of lithium and valproate were also more effective than either [drug alone]…in the studies of Findling et al. (2006),” and many patients needed stimulants in addition.

“Most children also needed combinations of mood stabilizers (lithium, carbamazepine, valproate) in the study [by] Kowatch et al. (2000).” In a 2017 study by Berk et al. of patients hospitalized for a first mania, randomization to lithium for one year was more effective than quetiapine on almost all outcome measures.

Targeting ADHD

“[The increased] severity of [the child’s] ADHD despite improving mania speaks to the…utility of adding a stimulant to the regimen that already includes…guanfacine,” which is a common non-stimulant treatment for ADHD. “This would be supported by the data of Scheffer et al. (2005) that stimulant augmentation for residual ADHD symptoms does not [worsen] mania, and that the combination of a stimulant and guanfacine may have more favorable effects than stimulants alone.”

However, the consensus in the field is that mood stabilization should be achieved first, before low to moderate (but not high) doses of stimulants are added. “Thus, in the face of an inadequate response to the lithium-risperidone combination in this child, stimulants could be deferred until better mood stabilization was achieved.”

Other Approaches to Mood Stabilization and Anxiety Reduction

“The anticonvulsant mood stabilizers (carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproate) each have considerable mood stabilizing and anti-anxiety effects, at least in adults with bipolar disorder. With inadequate mood stabilization of this patient on lithium and risperidone, we would consider the further addition of lamotrigine.

Lamotrigine appears particularly effective in adults with bipolar disorder who have a personal history and a family history of anxiety (as opposed to mood disorders), and it has positive open data in adolescents with bipolar depression and in a controlled study of maintenance (in teenagers 13–17, but not in preteens 10–12) (Findling et al. 2015). With better mood stabilization, anxiety symptoms usually diminish…, and we would pursue these strategies [instead of using] antidepressants for depression and anxiety in young children with bipolar disorder.”

“Carbamazepine appears to be more effective in adults with bipolar who have [no] family history of mood disorders,” unlike lithium, which seems to work better in people who do have a family history of mood disorders.

“While the overall results of oxcarbazepine in childhood mania were negative, they did exceed placebo in the youngest patients (aged 7–12) as opposed to the older adolescents (13–18) (Wagner et al. 2006).

“There are long-acting preparations of both carbamazepine (Equetro) and oxcarbazepine (Oxtellar) that would allow for all nighttime dosing to help with sleep and reduce daytime side effects and sedation. Although data [on] anti-manic and antidepressant effects in adults are stronger for carbamazepine than oxcarbazepine,” there are good reasons to consider oxcarbazepine. First, there is the finding mentioned above that oxcarbazepine worked best in the youngest children. Second, there is a lower incidence of severe white count suppression on oxcarbazepine. Third, it has less of an effect on liver enzymes than carbamazepine. However, low blood sodium levels are more frequent on oxcarbazepine than carbamazepine.

Other Atypical Antipsychotics That May Improve Depression

Omega-3 Fatty Acids Improve ADHD

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis found that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation improves symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. The article by Jane Pei-Chen Chang and colleagues in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology identified seven randomized controlled trials in which omega-3 fatty acids improved clinical symptoms of ADHD, and three trials in which omega-3s improved cognitive measures associated with attention.

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis found that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation improves symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. The article by Jane Pei-Chen Chang and colleagues in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology identified seven randomized controlled trials in which omega-3 fatty acids improved clinical symptoms of ADHD, and three trials in which omega-3s improved cognitive measures associated with attention.

The meta-analysis also found that children and adolescents with ADHD have lower than normal levels of the omega-3s DHA and EPA, in addition to lower total levels of omega-3s measured in blood and cheek tissues.

Chang and colleagues suggest that omega-3 fatty acid supplementation is a potentially helpful and largely risk-free treatment option for ADHD in children and adolescents.

Systematic Review Finds Bupropion is Effective for ADHD in Young People

A 2016 systematic review by Qin Xiang Ng in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology found that the antidepressant bupropion (Wellbutrin) can improve attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents.

A 2016 systematic review by Qin Xiang Ng in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology found that the antidepressant bupropion (Wellbutrin) can improve attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents.

The review identified 25,455 studies of bupropion for ADHD, but only six included children. All six studies showed that bupropion improved ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents. Head-to-head trials of bupropion and methylphenidate (one of the most common medications to treat ADHD, which most people know by the name Ritalin) found the drugs had similar efficacy rates, although a large double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study found that bupropion had a smaller effect size than methylphenidate.

In terms of side effects, methylphenidate was more likely to cause headaches than bupropion, but otherwise the drugs were similar.

Ng suggests that bupropion should be considered for the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents, but more large trials of the drug are needed. Bupropion may also help children whose ADHD appears alongside conduct, substance abuse, or depressive disorders.

Methylphenidate Does Not Cause Mania When Taken with a Mood Stabilizer

Methylphenidate is an effective treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ritalin may be the most commonly recognized trade name for methylphenidate, but it is also sold under the names Concerta, Daytrana, Methylin, and Aptensio. A 2016 article in the American Journal of Psychiatry reports that methylphenidate can safely be taken by people with bipolar disorder and comorbid ADHD as long as it is paired with mood-stabilizing treatment.

Methylphenidate is an effective treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ritalin may be the most commonly recognized trade name for methylphenidate, but it is also sold under the names Concerta, Daytrana, Methylin, and Aptensio. A 2016 article in the American Journal of Psychiatry reports that methylphenidate can safely be taken by people with bipolar disorder and comorbid ADHD as long as it is paired with mood-stabilizing treatment.

The study was based on data from a Swedish national registry. Researchers led by Alexander Viktorin identified 2,307 adults with bipolar disorder who began taking methylphenidate between 2006 and 2014. Of these, 1,103 were taking mood stabilizers including antipsychotic medications, lithium, or valproate, while 718 were not taking any mood stabilizing medications.

Among those who began taking methylphenidate without mood stabilizers, manic episodes increased over the next six months. In contrast, patients taking mood stabilizers had their risk of mania decrease after beginning treatment with methylphenidate.

Viktorin and colleagues suggest that 20% of patients with bipolar disorder may also have ADHD, so it is not surprising that 8% of patients with bipolar disorder in Sweden receive a methylphenidate prescription.

Mood-stabilizing drugs can worsen attention and concentration, so methylphenidate treatment can be helpful if it can be done without increasing manic episodes. However, Viktorin and colleagues suggest that due to the risk of increasing mania, anyone given a prescription for methylphenidate monotherapy should be carefully screened to rule out bipolar disorder.

The researchers confirmed that taking methylphenidate for ADHD while taking a mood stabilizer for bipolar disorder is a safe combination.

TDCS May Improve ADHD Symptoms

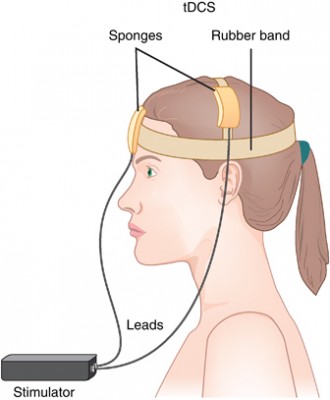

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a therapy in which electrodes placed on the skull deliver a steady, low level current to the brain, changing its threshold for electrical activity. Anodal tDCS to the prefrontal cortex can improve working memory. In a small 2017 study in the Journal of Neural Transmission, Cornelia Soff and colleagues found for the first time that tDCS may improve symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a therapy in which electrodes placed on the skull deliver a steady, low level current to the brain, changing its threshold for electrical activity. Anodal tDCS to the prefrontal cortex can improve working memory. In a small 2017 study in the Journal of Neural Transmission, Cornelia Soff and colleagues found for the first time that tDCS may improve symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

People with ADHD tend to have underactivation of the prefrontal cortex and deficits in working memory. The study randomized 15 young people aged 12–16 (three girls and twelve boys) to receive either real tDCS or a sham stimulation. The anodal tDCS was delivered at 1 mA targeting the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for 5 days. Those participants who received tDCS showed a reduction in inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity compared to those who received the sham stimulation. The effects were more pronounced 7 days after the stimulation, suggesting that tDCS’ effects may be long-term. Larger, more definitive trials are needed to clarify the effects of tDCS on ADHD, but these preliminary findings are promising.

Schizophrenia Drug May Treat ADHD with Impulsive Aggression

The atypical antipsychotic drug molindone was used to treat schizophrenia for decades before it was pulled from the market in 2010 for business reasons. Now Supernus Pharmaceuticals is studying whether a reformulation of the drug may be used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) that is accompanied by impulsive aggression.

Supernus tested an extended-release form of the drug in 118 children aged 6–12 with ADHD and impulsive aggression. They received either placebo or between 12mg and 54mg per day of molindone for 39 days. Those children who received between 12mg and 36mg per day of molindone showed fewer symptoms of impulsive aggression that those who received placebo. Side effects included headache, sedation, and increased appetite. Clinical trials of molindone will continue.