Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) Induces Gray-Matter Increases in Depression

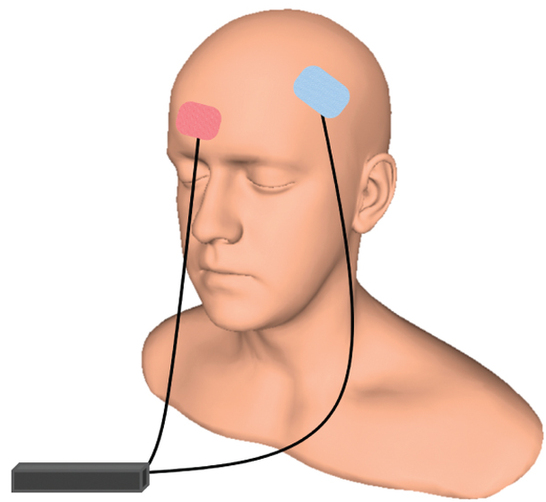

At the 2021 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry (SOBP), researcher Mayank Jog and colleagues described a study of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in 59 patients with moderate depression. The patients received either tDCS sessions that delivered electrical current at 2mA for 20 minutes or a same-length sham stimulation delivered using a double-blind stimulator, for a total of 12 sessions over 12 consecutive working days. Jog and colleagues found that compared to the sham stimulation, tDCS induced increases in gray matter volume in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) target area, with a statistically large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.3). The researchers plan to follow up this study that found structural changes to the brain after tDCS with more research on the antidepressant effects of the treatment.

Surface Area of Cortex Is Reduced After Multiple Manic Episodes

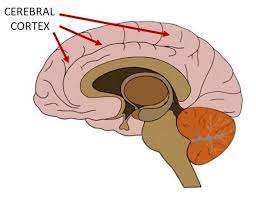

In a 2020 article in the journal Psychiatric Research: Neuroimaging, researcher Rashmin Achalia and colleagues described a study of structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that compared 30 people with bipolar I disorder who had had one or several episodes of mania to healthy volunteers. Compared to the healthy volunteers, people with bipolar disorder had “significantly lower surface area in bilateral cuneus, right postcentral gyrus, and rostral middle frontal gyri; and lower cortical volume in the left middle temporal gyrus, right postcentral gyrus, and right cuneus.”

The surface area of the cortex in patients with bipolar I disorder who had had a single episode of mania resembled that of the healthy volunteers, while those who had had multiple manic episodes had less cortical surface area.

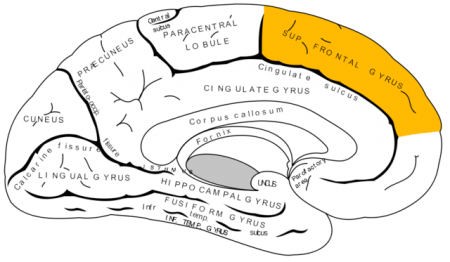

The data suggest that compared to healthy volunteers, people with bipolar disorder have major losses in brain surface area after multiple episodes that are not seen in first episode patients. In addition, the researchers found that both the number of episodes and the duration of illness was correlated with the degree of deficit in the thickness in the left superior frontal gyrus. These decreases in brain measures occurred after an average of only 5.6 years of illness.

Editor’s Note: These data once again emphasize the importance of preventing illness recurrence from the outset, meaning after the first episode. Preventing episodes may prevent the loss of brain surface and thickness.

Clinical data has also shown that multiple episodes are associated with personal pain and distress, dysfunction, social and economic losses, cognitive deficits, treatment resistance, and multiple medical and psychiatric comorbidities. These and other data indicate that treatment after a first episode must be more intensive, multimodal, and continuous and include expert psychopharmacological and psychosocial support, as well as family education and support. Intensive treatment like this can be life-saving. The current study also supports the mantra we have espoused: prevent episodes, protect the brain and the person.

Inflammation Predicts Lower Frontal and Temporal White Matter Volumes in Early-Stage Bipolar Disorder

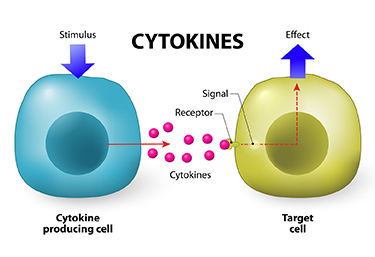

At the 2019 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, researcher David Bond found that seven inflammatory cytokines predicted lower white matter volumes in the left frontal and bilateral temporal lobes, as well as in the cingulate and inferior frontal gyri. Cytokines are secreted by some immune cells and send signals that can produce an effect in other cells.

At the 2019 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, researcher David Bond found that seven inflammatory cytokines predicted lower white matter volumes in the left frontal and bilateral temporal lobes, as well as in the cingulate and inferior frontal gyri. Cytokines are secreted by some immune cells and send signals that can produce an effect in other cells.

Bond noted that greater inflammation did not predict lower parietal or occipital white matter volumes, suggesting that inflammation had a greater effect on white matter volume in those parts of the brain most closely linked to mood disorders.

Different Types of Trauma Affect Brain Volume Differently

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been associated with decreased volume of gray matter in the cortex. Research by Linghui Meng and colleagues has revealed that the specific types of trauma that precede PTSD affect gray matter volume differently.

At the 2016 meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, Meng reported that PTSD from accidents, natural disasters, and combat led to different patterns of gray matter loss. PTSD from accidents was associated with gray matter reductions in the bilateral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). PTSD from natural disasters was linked to gray matter reductions in the mPFC and ACC, plus the amygdala and left hippocampus. PTSD from combat reduced gray matter volume in the left striatum, the left insula, and the left middle temporal gyrus.

Meng and colleagues also found that severity of PTSD was linked to the severity of gray matter reductions in the bilateral ACC and the mPFC.

In a 2016 article in the journal Scientific Reports, Meng and colleagues reported that single-incident traumas were associated with gray matter loss in the bilateral mPFC, the ACC, insula, striatum, left hippocampus, and the amygdala, while prolonged or recurrent traumas were linked to gray matter loss in the left insula, striatum, amygdala, and middle temporal gyrus.

Marker of Heart Failure May Predict Brain Deterioration

A protein released into the blood in response to heart failure may be able to predict brain deterioration before clinical symptoms appear. The protein, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), is released when cardiac walls are under stress. High levels of NT-proBNP in the blood are a sign of heart disease. A 2016 Dutch study indicated that high levels of NT-proBNP in the blood are also linked to smaller brain volume, particularly small gray matter volume, and to poorer organization of the brain’s white matter. The study by researcher Hazel I. Zonneveld and colleagues, published in the journal Neuroradiology, assessed heart and brain health in 2,397 middle-aged and elderly people with no diagnosed heart or cognitive problems.

A protein released into the blood in response to heart failure may be able to predict brain deterioration before clinical symptoms appear. The protein, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), is released when cardiac walls are under stress. High levels of NT-proBNP in the blood are a sign of heart disease. A 2016 Dutch study indicated that high levels of NT-proBNP in the blood are also linked to smaller brain volume, particularly small gray matter volume, and to poorer organization of the brain’s white matter. The study by researcher Hazel I. Zonneveld and colleagues, published in the journal Neuroradiology, assessed heart and brain health in 2,397 middle-aged and elderly people with no diagnosed heart or cognitive problems.

Researchers are working to clarify the relationship between cardiac dysfunction and preliminary brain disease, but researcher Meike Vernooij says it is likely cardiac dysfunction comes first and leads to brain damage. Measuring biomarkers such as NT-proBNP may help identify brain diseases such as stroke and dementia earlier and allow for earlier treatment and lifestyle changes that can slow or reverse the course of disease.

Bipolar Disorder and Diabetes Linked

A systematic literature review in 2016 showed a definitive link between bipolar disorder and diabetes. Bipolar disorder almost doubles the risk of diabetes while diabetes more than triples the risk of bipolar disorder. The article by Ellen F. Charles and colleagues was published in the International Journal of Bipolar Disorders.

A systematic literature review in 2016 showed a definitive link between bipolar disorder and diabetes. Bipolar disorder almost doubles the risk of diabetes while diabetes more than triples the risk of bipolar disorder. The article by Ellen F. Charles and colleagues was published in the International Journal of Bipolar Disorders.

The review included seven large cohort studies. The studies, based on elderly populations only, examined bipolar disorder and diabetes rates. Charles and colleagues suggested that shared mechanisms could cause both illnesses. New disease models that explain the link between bipolar disorder and diabetes could lead to better treatments.

The review also reported that both bipolar disorder and diabetes were independently associated with risk of cognitive decline and dementia in these elderly individuals. People with diabetes had more brain atrophy on average than others who share their age and gender but did not have diabetes. People with bipolar disorder who also had diabetes and either insulin resistance or glucose intolerance had neurochemical changes in the prefrontal cortex that indicated poor neuronal health. In some cases, these patients also had reduced brain volume in the hippocampus and cortex.

Kynurenine Pathway Suggests How Inflammation is Linked to Schizophrenia

The kynurenine pathway describes the steps that turn the amino acid tryptophan (the ingredient in turkey that might make you sleepy) into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. This pathway might be a connection between the immune system and neurotransmitters involved in schizophrenia.

A recent autopsy study by researcher Thomas Weickert and colleagues explored this link by determining that in the brains of people with schizophrenia and high levels of inflammation, messenger RNA for Kynurenine Aminotransferase II (KATII, a step on the kynurenine pathway) was elevated in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex compared to the brains of people who died healthy and those with schizophrenia but low levels of inflammation.

The KATII mRNA levels also correlated with mRNA levels of inflammatory markers such as glial fibrillary acidic protein and interleukin-6.

Blood measures related to the kynurenine pathway also differentiated people with schizophrenia from healthy controls. People with schizophrenia had lower levels of tryptophan, kynurenine, and kynurenic acid in their blood. The low levels of kynurenic acid in the blood were correlated with deficits in working memory and smaller volume of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Weickert and colleagues suggest that blood levels of kynurenic acid might provide a measurable indicator of the degree to which people with schizophrenia are experiencing problems with executive functioning (planning and decision-making) and loss of brain volume.

Brain Volumes Affected by Type and Timing of Childhood Abuse

Maltreatment during childhood has been linked to brain changes and mental illness. In a study by researcher Carl M. Anderson and colleagues that was presented at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, maltreatment at particular ages was statistically linked to deficits in the size of certain brain areas in young adulthood.

The brain areas under examination are critical for the regulation of emotion and behavior, and this research suggests that early experiences can stunt their development, perhaps through altered production of synapses or via the synaptic pruning process that occurs during preadolescence. The details, summarized below, are perhaps less important than the overall finding that maltreatment in childhood affects brain volume, and this effect varies based on the timing and type of maltreatment. Abuse and neglect earlier in life affected the left side of the brain, while later maltreatment affected the right side.

Severity of physical abuse at age 3 affected the volume of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in women. Physical abuse at ages 3 and 8 in men affected left ventromedial prefrontal cortical volume, while later abuse at ages 7 and 12 predicted volume of the right side.

In women, dorsal anterior cingulate area on the left was predicted by physical abuse at age 5 and by emotional neglect at ages 7 and 11. Later emotional neglect at ages 15 and 16 and physical abuse by a peer at age 10 was associated with smaller right dorsal anterior cingulate. In men, smaller left dorsal anterior cingulate area was predicted by physical neglect at age 2 and emotional abuse by a peer and witnessing abuse of a sibling at ages 5 and 10, and right area by physical neglect at age 12.

Lithium Increases Cortical Thickness in People with Bipolar Disorder

Recent studies have indicated that bipolar disorder is associated with changes to brain volume, including thinning of the cortex. In research presented at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, researcher Noha Abdel Gawad reported that four weeks of lithium treatment increased cortical thickness in the left superior frontal gyrus. This is the third replication of this finding.

Recent studies have indicated that bipolar disorder is associated with changes to brain volume, including thinning of the cortex. In research presented at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, researcher Noha Abdel Gawad reported that four weeks of lithium treatment increased cortical thickness in the left superior frontal gyrus. This is the third replication of this finding.

Other research has established that lithium treatment also increases the volume of the hippocampus in people with bipolar disorder. Together the findings provide strong evidence that lithium treatment protects neurons and can reverse brain changes associated with bipolar disorder.

Bad Habits May Reduce Brain Volumes, May Cause Dementia

Smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and diabetes aren’t just harmful to the body. They may actually lead to dementia.

Behavioral risk factors for cardiovascular disease like those listed above have been linked to reduced volume in the brain as a whole and several brain regions, including the hippocampus, precuneous, and posterior cingulate cortex. A 2015 study by researcher Kevin King and colleagues found that these reduced brain volumes are early indicators of cognitive decline.

King and colleagues analyzed data on 1,629 participants in the long-term Dallas Heart Study. Their cardiovascular risk factors were assessed when they began the study, and their brain volume and cognitive function were measured seven years later.

Alcohol use and diabetes were associated with lower total brain volumes, while smoking and obesity were linked to low volumes in the posterior cingulate cortex.

Low hippocampal volume was linked to past alcohol use and smoking, while lower precuneous volume was linked to alcohol use, obesity, and blood glucose levels.King and colleagues suggested that subtle differences in brain volumes in midlife are the first sign of developing dementia in participants who were still younger than 50 years of age.