Family History of Alcohol Dependence Predicts Antidepressant Response to an NMDA Antagonist

LE Phelps reported in Biol. Psy (2009) that subjects with a family history of alcohol dependence showed significantly greater improvement in MADRS scores compared with subjects who had no family history of alcohol dependence.

They concluded that a family history of alcohol dependence appears to predict a rapid initial antidepressant response to the NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine.

Bipolar Disorder Patients Respond to Ketamine, Esketamine Treatment

(Reposted from the Yale School of Medicine blog)

A small sample of patients with bipolar disorder displayed noteworthy improvement in their depressive symptoms after being treated with the rapid-acting antidepressant intravenous ketamine and the nasal spray esketamine, according to a new Yale led-study.

The study, published October 2 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, also found that patients were not at higher risk of suffering a manic episode during the acute phase of treatment.

Intramuscular versus Intravenous Ketamine for the Management of Treatment-Resistant Depression and Suicidal Ideation

Cristina Albott of the University of Minnesota Medical School reported relatively similar efficacy of intramuscular versus intravenous ketamine for the management of treatment-resistant depression and suicidal ideation in outpatient settings.

“Intramuscular (IM) delivery represents an underexplored and promising route of administration given its high bioavailability and low cost….Sixty-six patients underwent a series of 7 to 9 IV (n=35) or IM (n=31) administrations of 0.5mg/kg ketamine during a 21-28 day period. Both IV and IM showed similar magnitudes of improvement in depression, but surprisingly only the IM route was associated in a significant improvement in suicidal ideation in a within subjects change.”

“No adverse events occurred throughout the treatment series for either administration route…. This clinical case series provides preliminary support for the effectiveness and safety of IM compared to IV ketamine in TRD. “

NEW DATA ON EXTENDING THE EFFFECTS OF IV KETAMINE: Implications for countering the effects of stigma.

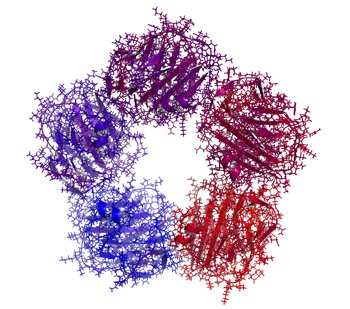

John Krystal of Yale U. in an article in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sci. (2023) gave new information about the anatomical and physiological effects of ketamine and about how to extend its effects. Ketamine in animals acutely (in a matter of hours) increases spines, synapses, and dendrites and physiological connectivity in neurons in the prefrontal cortex. Data now support these findings in humans with depression, but AD effects of ketamine tend to dissipate over a period of 3 to 5 days and require repeated infusions to maintain the improvement. Synaptic density can be measured with SV2A and this can be enhanced with a Navitor Pharmaceuticals drug acting on mTORC1. Surprisingly low doses of rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR1, extends the duration of AD effects of ketamine, increasing the response rate at 2 weeks of 13% to 41%. Ketamine restores only the spines that have been reduced in depression and rapamycin is thought to extend the duration of the restored spines. It may do this by increasing the neurotropic effects of microglia. The tripartite synapse of pre and post synaptic neurons and astrocytes, may now be better described as the tetrapartite synapse with the inclusion of microglial.

Adding psychotherapy to the effects of ketamine in PTSD increases and extends efficacy.

AD effects of ketamine can be extended with cognitive behavioral therapy. Thus, ketamine increases synaptic efficacy, synaptic density, glutamate homeostasis, and experience-dependent neuroplasticity. Extending the persistence of these effects by various chemical and psychotherapeutic mechanisms may give new ways of enhancing and prolonging the therapeutic effects of this rapidly acting agent.

Interestingly, Kaye at Yale U. reports that in contrast to transient effects of ketamine, the AD effects of therapy-assisted psilocybin appear to be very long lasting and the associated increases in spines persist for longer than 37 days. Another psychedelic MDMA that is effective in PTSD causes large increases in spines, although they are less persistent and are gone by 34 days.

Editors Note: As we have previously highlighted in the BNN, these data on ketamine and other psychedelics reversing the anatomical and physiological deficits in prefrontal neurons of depressed animals and humans (spines, dendrites, synapses and intercellular communication), give a new view of the real, reliable, and replicable neurological defects accompanying depression. The rapid correction of these neural abnormalities in conjunction with the rapid induction of antidepressant effects are not only paradigm shifting from a treatment perspective, but have major implications for the assertion that there is a neurobiological basis of depression and its treatment.

As such, these data should do much to counter the continuing stigma too often accompanying the term “mental” illness that it is somehow not as real as other medical and neurological conditions, and as it is often asserted that “it is just all in one’s head.” This picks up on the unfortunate associations and definitions of “mental” as imaginary, all in the mind, and evanescent and that mental illness can readily be countered with effort and will power such as “pulling oneself up by the bootstraps,” (the latter of which is in itself a logical impossibility.)Intravenous Arketamine As Adjunctive Treatment for Bipolar Depression

Highlights from Posters Presented at the Society of Biological Psychiatry Meeting, April 27-29, 2023 in San Diego

I.D. Bandeira of Stanford University reported on the feasibility and safety of the (R)-enantiomer of ketamine (arketamine) in treating six patients with bipolar depression: “Subjects received two intravenous infusions of arketamine of 0.5mg/kg, followed by 1mg/kg one week later.” Patients improved after the first dose and after “1mg/kg dose, the mean MADRS [Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale] total score before the second infusion was 32.0, which dropped to 17.66 after 24h (p<0.001).” All individuals tolerated both doses, exhibiting no dissociative or manic symptoms.

Effectiveness of Repeated Ketamine Infusions for Treatment Resistant Bipolar Depression

Highlights from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Conference Posters and Presentations, Chicago, June 22-25, 2023

Farhan Fancy, of the University of Toronto, gave 66 highly treatment resistant (unselected) bipolar I or II patients four sub-anesthetic doses of IV ketamine (0.5-0.75mg/kg) over a two-week period. They saw significant reductions in depression, anxiety, suicidality, and disability. Response rates were 35% and remission rate was 20%. “Infusions were generally well tolerated with treatment-emergent hypomania observed in only three patients (4.5%) with zero cases of mania or psychosis.”

“Pharmacotherapy of Bipolar Depression”

Roger McIntyre gave a talk on the “Pharmacotherapy of Bipolar Depression” at the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Conference in Chicago, June 22-25, 2023

He pointed out that, contrary to the many approved agents for mania, there were few FDA-approved drugs for depression in patients with Bipolar Disorders. These approved drugs included: cariprazine (Vraylar); lumateperone (Caplyta); lurasidone (Latuda); quetiapine (Seroquel); and the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination (Symbyax). Other non-approved agents include: lithium, lamotrigine, antidepressants, MAOIs, pramipexole, carbamazepine, ketamine, bupropion+dextromethorphan, amantadine, memantine, and possibly minocycline and celecoxib. Surprisingly, more than 3,000 bipolar depressed patients have been reported to be taking ketamine and that this was not associated with the induction of hypomania or mania.

McIntyre reported on the antidepressant (AD) effects of intra-nasal (i.n.) insulin. The insulin receptor sensitizer metformin had AD effects, but only in those who converted to insulin sensitivity.

McIntyre reported on the mixed effects of the GLP-1 agonists in the prevention of depression (Cooper et al J. Psychiatric Res, 2023). This is of interest in relationship to the bidirectional relationship of diabetes mellitus and depression.

Liraglutide appeared to have an anti-anhedonia effect. Semaglutide had AD and antianxiety effects in animal models of depression.

Recent studies have explored the antidepressant effect of psilocybin. Small studies have indicated that it has rapid onset of AD effects, and, in contrast to ketamine where rapid onset AD and anti-suicidal effects are short lived, the AD effect of psilocybin may be more prolonged.

Ketamine repairs structure and function of prefrontal cortical neurons via glutamate NMDA receptor blocking action, while psilocybin and other psychedelics act via stimulating 5HT2A receptors. One single case study suggested that blocking 5HT2A receptors with trazodone could achieve a rapid onset of AD effects of psilocybin without the psychedelic effects, a very interesting finding that requires replication.

Higher Brain Temperature in Youth Bipolar Disorder Using a Novel Magnetic Resonance Imaging Approach

Highlights from Posters Presented at the Society of Biological Psychiatry Meeting, April 27-29, 2023 in San Diego

Ben Goldstein of the University of Toronto reported that “Brain temperature was significantly higher in BD (bipolar youth) compared to CG (control group) in the precuneus. Higher ratio of brain temperature-to-CBF [cerebral blood flow] was significantly associated with greater depression symptom severity in both the ACC [anterior cingulate cortex] and precuneus within BD.”

These finding are of particular interest in light of the Unspecified Bipolar Disorder subtype called Temperature and Sleep Dysregulation Disorder (TSDD), where patients are over heated and respond to clonidine and other cooling techniques along with lithium and repeated intranasal ketamine insufflations.

Childhood Physical Abuse Predicts Response to IV Ketamine

At a recent scientific meeting, researcher Alan Swann reported the results of a study of intravenous ketamine in people with treatment-resistant depression. The 385 participants, who received four infusions of IV ketamine at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg, could be grouped into three based on their type of response to the treatment.

One group had moderate depression at baseline and showed little change. A second group with severe baseline depression also showed minimal improvement. A third group who also had severe baseline depression had a rapid and robust antidepressant response to the treatment. This group had high scores relating to physical abuse on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), but did not differ on other clinical variables. Swann and colleagues concluded, “Our outcomes show that IV ketamine should be considered as a primary treatment option for adults presenting with severe, treatment resistant depression and a self-reported history of childhood physical abuse. IV ketamine may not be as effective for moderately depressed individuals irrespective of childhood maltreatment.”

Baseline Levels of CRP Could Help Predict Clinical Response to Different Treatments

C-reactive protein, or CRP, is a marker or inflammation that has been linked to depression and other illnesses. People with high levels of CRP respond differently to medications than people with lower CRP, so assessing CRP levels may help determine which medications are best to treat a given patient.

High baseline levels of CRP (3–5pg/ml) predict a poor response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (SSRIs) and to psychotherapy, and are associated with increased risk of recurrent depression, heart attack, and stroke.

However, high baseline CRP predicts a better response to the antidepressants nortriptyline and bupropion. High CRP is also associated with better antidepressant response to infliximab (a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the inflammatory cytokine TNF alpha), while low levels of CRP predict worsening depression upon taking infliximab.

High baseline CRP also predicts good antidepressant response to intravenous ketamine (which works rapidly to improve treatment-resistant depression), minocycline (an anti-inflammatory antibiotic that decreases microglial activation), L-methylfolate (a supplement that can treat folate deficiency), N-acetylcysteine (an antioxidant that can improve depression, pathological habits, and addictions), and omega-3 fatty acids (except in people with low levels of DHA).

High baseline CRP also predicts a good response to the antipsychotic drug lurasidone (marketed under the trade name Latuda) in bipolar depression. In people with high baseline CRP, lurasidone’s positive results have a huge effect size of 0.85, while in people with low CRP (<3pg/ml) the improvement on lurasidone has a smaller effect size (0.35).

In personal communications with this editor (Robert M. Post) in 2018, experts in the field (Charles L. Raison and Vladimir Maletic) agreed that assessing baseline CRP levels in a given patient could help determine optimal strategies to treat their depression and predict the patient’s responsiveness to different treatment approaches.

At a 2018 scientific meeting, researchers Cynthia Shannon, Thomas Weickert, and colleagues reported that high baseline levels of CRP were associated with symptom improvement in patients with schizophrenia when they were treated with the drug canakinumab (marketed under the trade name Ilaris). Canakinumab is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 beta (Il-1b). Il-1b is elevated in a subgroup of patients with depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia, and CRP levels are an indication of the associated inflammation.