Carbamazepine Extended Release Has Mixed Effects in Bipolar Children

In a poster presentation at the Pediatric Bipolar Conference in Cambridge, Massachusetts in March, Gagin Joshi from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) presented positive data from a study on the use of carbamazepine extended release (Equetro) in 27 children ages 6 to 12 with childhood-onset bipolar illness. These data were published this year in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology.

Joshi found substantial overall improvement using an average dose of 788 mg/day, achieving blood levels averaging 6.6 mcg/l. Surprisingly, antidepressant effects were as robust as antimanic effects.

Major side effects included headache in 23% of participants, gastrointestinal upset in 18%, sedation in 15%, and dizziness in 8%. However, eleven children dropped out of the study prematurely (two for rash, three for mania, three for lack of efficacy, and three who did not participate in follow up). Joshi felt that carbamazepine extended release was a useful backup strategy, but he was not overly impressed with its overall profile in children, in part because of the high dropout rate.

Treatments Studies for Childhood Onset Bipolar Illness Are Inadequately Funded

It was remarkable that at the Pediatric Bipolar Conference hosted by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the Ryan Licht Sang Bipolar Foundation this past March in Cambridge, Massachusetts, none of the plenary talks, although they were excellent and given by leaders in the field of child psychiatry, dealt directly with the topic of the conference–childhood-onset bipolar disorder. There were also no reports of systematic placebo-controlled clinical trials evaluating treatment approaches in any of the subsequent presentations or posters. A number of open and uncontrolled studies examined new treatment possibilities.

It is notable that the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) no longer sponsors this conference, as it did for many years. Moreover, STEP-BD, an NIMH-sponsored research program on the course and treatment of adult-onset bipolar disorder, is now defunct, and the head of STEP-BD and one of the most productive researchers in bipolar illness, Andrew Nierenberg from the MGH, has been forced to search for other funding opportunities.

These developments highlight the ongoing deficient funding and study of both childhood-onset and adult-onset bipolar disorder despite the enormous public health impact, extraordinary morbidity, and early mortality from suicide and medical illnesses like cardiovascular disease that are associated with these disorders.

Revisions of the DSM-V Related to Bipolar Disorder in Children

The Pediatric Bipolar conference in March ended with a discussion led by Ellen Leibenluft and Danny Pine of the NIMH about possible changes in the diagnostic criteria for childhood onset bipolar disorder being considered for the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), which will be finalized in the next few years. There has been an increase in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children in the past decade, and many have attributed this to over-diagnosis. Controversy about the precise symptoms and thresholds for diagnosis has been prominent in the literature and in the popular press.

The Pediatric Bipolar conference in March ended with a discussion led by Ellen Leibenluft and Danny Pine of the NIMH about possible changes in the diagnostic criteria for childhood onset bipolar disorder being considered for the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), which will be finalized in the next few years. There has been an increase in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children in the past decade, and many have attributed this to over-diagnosis. Controversy about the precise symptoms and thresholds for diagnosis has been prominent in the literature and in the popular press.

The major change proposed was that the syndrome of severe mood dysregulation (SMD) described by Leibenluft et al. in 2003, may be called Temper Dysregulation Disorder (TDD), and would not be considered part of the bipolar spectrum. This is in part because SMD is not associated with an increased incidence of a positive family history of bipolar illness. Part of the motivation for separating TDD from bipolar illness is to cut down on what some consider the over-diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children.

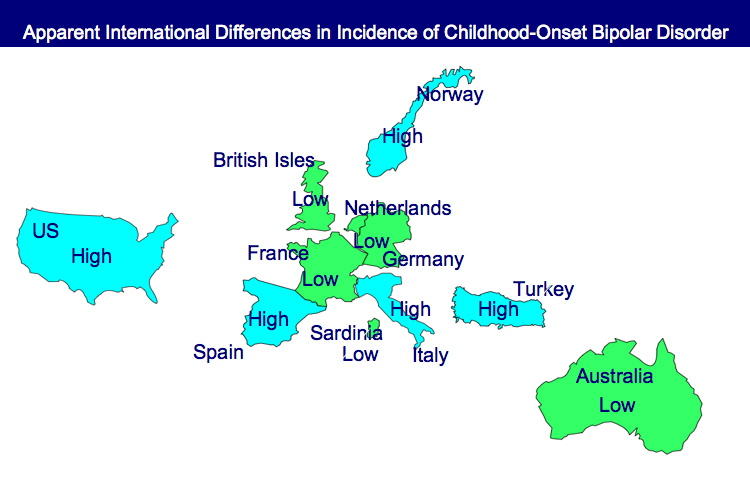

Incidence of Childhood Onset Bipolar Disorder Varies Geographically: More in US than Europe

A poster by Aditya Sharma of Newcastle University and colleagues at the Pediatric Bipolar Conference assessed the incidence of childhood-onset bipolar illness based on monthly letters sent to approximately 750 consultants in child and adolescent psychiatry in the British Isles. Only five confirmed cases were reported, with the youngest child being 11 years old.

EDITOR’S NOTE: These data are of particular interest in relationship to earlier data indicating that childhood-onset bipolar disorder may be relatively rare in some European countries, including the British Isles, France, the Netherlands, and Germany, as well as in Australia, South Korea, and New Zealand.

In contrast, childhood-onset bipolar illness with an onset prior to age 13 appears to be prevalent in the US, with one-fifth to one-quarter of adult outpatients reporting onsets of either depression with dysfunction or mania prior to age 13. Another substantial group of patients report onsets in adolescence, indicating that some 50-66% of bipolar illness in the US begins in either childhood or adolescence.

Similarly higher amounts of childhood-onset bipolar illness are reported in Italy, Turkey, and Norway, indicating some heterogeneity of vulnerability factors and course of illness outcomes among different European countries.

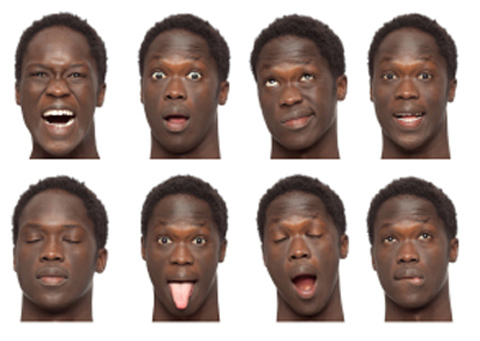

Consistent Deficits In Facial Emotion Recognition Found in Non-Ill Children of Parents with Bipolar Disorder

Children with bipolar parents may have difficulty identifying the emotions they see on another person’s face. Aditya Sharma of Newcastle University presented a poster at the Pediatric Bipolar Conference in Cambridge, Massachusetts in March, which indicated that children without bipolar disorder but at risk because a parent has the illness showed deficits in facial emotion recognition. Similar results were reported by Brotman et al. in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2008. Since children of bipolar parents are at increased risk of developing the disease, this deficit in labeling facial emotion may be a marker of early bipolar disorder or a risk factor for its onset.

Editor’s Note: These types of deficits in facial emotion recognition have been consistently observed in adults and children diagnosed with bipolar disorder, so assessing whether children can successfully identify others’ facial emotions could become part of the assessment of risk for bipolar disorder. This deficit could also be targeted for psychosocial intervention and rehabilitative training to enhance emotion recognition skills. Such an approach could improve interpersonal communication and lessen hypersensitive responses to perceived emotional threats and negative emotional experiences.

Help the Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation win $250,000!

The Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation (CABF) has launched a campaign for votes to win the Pepsi Refresh Project and a $250,000 grant to aid families and children living with bipolar disorder and depression. CABF has been chosen to compete for the top grant during the month of November. Winners are decided by total votes cast via Internet and text messages throughout the month.

If selected by popular vote, CABF will use an innovative

social media awareness effort to:

- Elevate awareness about bipolar disorder & depression in children;

- Educate parents & the public about the symptoms;

- Explain the best treatment options & ways to reduce teen suicide;

- Expand the number of children receiving treatment;

- Eliminate the stigma associated with mental illness;

- Extend hope to families struggling with mental illnesses.

Supporters can vote for CABF 3 times a day, once from

each of the following sources:

1. Pepsi Refresh website

2. Facebook

3. Texting – Text 104174 to PEPSI (73774) (Normal text

rates apply).

5 Myths About Unipolar Depression

Early this year, news stories such as Newsweek’s “The Depressing News About Antidepressants” and “Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity” in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) created an inadequate picture of the seriousness of clinical depression, and the importance of preventing recurrent episodes with long-term antidepressant treatment. (For a rebuttal, see Psychiatric Times.)

Early this year, news stories such as Newsweek’s “The Depressing News About Antidepressants” and “Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity” in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) created an inadequate picture of the seriousness of clinical depression, and the importance of preventing recurrent episodes with long-term antidepressant treatment. (For a rebuttal, see Psychiatric Times.)

The consequences of this distorted depiction of depression and its treatment are potentially dire for individuals’ health. Some of the popular myths about depression deserve critical review so that patients can make more informed decisions about their own treatment.

Myth 1: Depression is all in your mind

Myth 2: Depression is over-treated

Myth 3: Antidepressant efficacy barely exceeds that of placebo

Myth 4: Antidepressants should be stopped as soon as possible

Myth 5: Depression is a minor medical problem

Myth 1: Depression is all in your mind

This might seem valid, since depression is classified as a mental illness. But depression is not abstract, imaginary, or lacking a solid physical foundation. There is now overwhelming evidence that depression coincides with disturbances in multiple brain and body systems.