ADHD Common in People with Mood Disorders

In a meta-analysis published in the journal Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica in 2021, researcher Andrea Sandstrom and colleagues reported that people with mood disorders had a three times higher incidence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than people without mood disorders. ADHD was also more likely to occur in people with bipolar disorder than in people with major depression. The comorbidity is most common in childhood, less so in adolescence, and lowest in adulthood.

Based on 92 studies including a total of 17,089 individuals, the prevalence of ADHD in people with bipolar disorder is 73% in childhood, 43% in adolescence, and 17% in adulthood. Data from 52 studies with 16,897 individuals indicated that prevalence of ADHD in major depressive disorder is 28% in childhood, 17% in adolescence, and 7% in adulthood.

Editor’s Note: A key implication of this research is that there is a huge overlap of bipolar disorder and ADHD in childhood, and that physicians need to specifically look for bipolar symptoms that are not common in ADHD to make a correct diagnosis. These include: brief or extended periods of mood elevation and decreased need for sleep in the youngest children; suicidal or homicidal thoughts and threats in slightly older children; hyper-sexual interests and actions; and hallucinations and delusions. When these are present, even when there are also clear-cut ADHD symptoms, a clinician must consider a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and treat the child with mood stabilizers prior to using stimulants or other traditional ADHD medications.

Conversely, physicians should be aware of the much lower incidence of ADHD in adolescents and adults with bipolar disorder. Here one should first make sure that the apparent ADHD symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, poor concentration, etc. do not result from inadequately treated mania and depression, and if they do, treat these symptoms to remission prior to using traditional ADHD medications.

Clinical Risk Prediction in Youth at Risk for Bipolar Spectrum Disorder and Relapse

Researchers from two 15-year studies of bipolar youth, COBY (The Coarse and Outcome of Bipolar Youth Study) and BIOS (Bipolar Offspring Family Study), have used the longitudinal data from their studies in order to create a risk calculator that can predict an individual’s likelihood of illness.

At the 2020 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, researcher Danella Hafeman presented research on a risk calculator that predicts the 5-year risk for onset of a bipolar disorder spectrum diagnosis (BPSD) in young people at high risk and can reasonably distinguish those who will receive a diagnosis from those who will not.

Some of the factors used in the risk calculator include dimensional measures of mania, depression, anxiety, and mood lability; psychosocial functioning; and the age at which parents were diagnosed with a mood disorder.

Hafeman reported that there was a 25% risk that offspring of a bipolar parent would develop a bipolar disorder spectrum diagnosis. In a population ranging in age from 6 to 18 years, Hafeman and colleagues found that anxiety and depression symptoms were a sign of vulnerability to a bipolar spectrum disorder, while subthreshold manic symptoms indicated that a bipolar spectrum disorder could soon emerge. Sudden or exaggerated changes in mood were also an important predictor of BPSD.

Hafeman and colleauges noted that even in children as young as 2 to 5 years old, there were already signs of anxiety, aggression, attention problems, depression, and sudden mood changes in those who would go on to receive a diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorder.

The researchers were also able to predict which patients with BPSD would have a relapse. According to Hafeman and colleagues, “The most influential recurrence risk factors were shorter recovery lengths, younger age at assessment, earlier mood onset, and more severe prior depression.”

Editor’s Note: Offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder are at high risk for anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder, and bipolar disorder. Parents should be alert for the symptoms of these illnesses and seek evaluation and treatment for their children as necessary. Parents should also be aware of the risk factors above that contributed to the risk calculator.

Parents can aid physicians in their evaluation by joining our Child Network and keeping weekly ratings of their children’s symptoms of depression, anxiety, ADHD, oppositional behavior, and mania.

Schizophrenia: The Importance of Catching It Early

By the time psychosis appears in someone with schizophrenia, biological changes associated with the illness may have already been present for years. A 2015 article by R.S. Kahn and I.E. Sommer in the journal Molecular Psychiatry describes some of these abnormalities and how treatments might better target them.

One such change is in brain volume. At the time of diagnosis, schizophrenia patients have a lower intracranial volume on average than healthy people. Brain growth stops around age 13, suggesting that reduced brain growth in people with schizophrenia occurs before that age.

At diagnosis, patients with schizophrenia show decrements in both white and grey matter in the brain. Grey matter volume tends to decrease further in these patients over time, while white matter volume remains stable or can even increase.

Overproduction of dopamine in the striatum is another abnormality seen in the brains of schizophrenia patients at the time of diagnosis.

Possibly years before the dopamine abnormalities are observed, underfunctioning of the NMDA receptor and low-grade brain inflammation occur. These may be linked to cognitive impairment and negative symptoms of schizophrenia such as social withdrawal or apathy, suggesting that there is an at-risk period before psychosis appears when these symptoms can be identified and addressed. Psychosocial treatments such as individual, group, or family psychotherapy and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation have both been shown to decrease the rate of conversion from early symptoms to full-blown psychosis.

Using antipsychotic drugs to treat the dopamine abnormalities is generally successful in patients in their first episode of schizophrenia. Use of atypical antipsychotics is associated with less brain volume loss than use of the older typical antipsychotics. Treatments to correct the NMDA receptor abnormalities and brain inflammation, however, are only modestly effective. (Though there are data to support the effectiveness of the antioxidant n-acetylcysteine (NAC) on negative symptoms compared to placebo.) Kahn and Sommer suggest that applying treatments when cognitive and social function begin to be impaired (rather than waiting until psychosis appears) could make them more effective.

The authors also suggest that more postmortem brain analyses, neuroimaging studies, animal studies, and studies of treatments’ effects on brain abnormalities are all needed to clarify the causes of the early brain changes that occur in schizophrenia and identify ways of treating and preventing them.

Offspring of Parents with Psychiatric Disorders At Increased Risk for Disorders of Their Own

At a symposium at the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorder, researcher Rudolph Uher discussed FORBOW, his study of families at high risk for mood disorders. Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and severe depression are at higher risk for a variety of illnesses than offspring of healthy parents.

Uher’s data came from a 2014 meta-analysis by Daniel Rasic and colleagues (including Uher) that was published in the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin. The article described the risks of developing mental illnesses for 3,863 offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression compared to offspring of parents without such disorders.

Previous literature had indicated that offspring of parents with severe mental illness had a 1-in-10 likelihood of developing a severe mental illness of their own by adulthood. Rasic and colleagues suggested that the risk may actually be higher—1-in-3 for the risk of developing a psychotic or major mood disorder, and 1-in-2 for the risk of developing any mental disorder. An adult child may end up being diagnosed with a different illness than his or her parents.

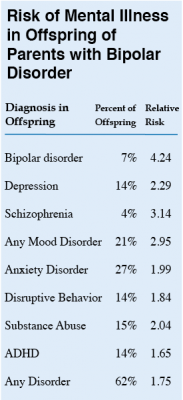

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

Editor’s Note: These data emphasize the importance of vigilance for problems in children who are at increased risk for mental disorders because they have a family history of mental disorders. One way for parents to better track mood and behavioral symptoms is to join our Child Network.

Brain Activity Differentiates Youth with Bipolar Disorder from Youth with Unipolar Depression

Both bipolar disorder and unipolar depression often begin in childhood or adolescence, but it can be difficult to distinguish the two using symptoms only. People with bipolar illness may go a decade without receiving a correct diagnosis. Researcher Jorge Almeida and colleagues recently performed a meta-analysis of previous studies to determine what neural activity is typical of children with bipolar disorder versus children with unipolar depression while processing images of facial emotion. They found that youth with bipolar disorder were more likely to show limbic hyperactivity and cortical hypoactivity during emotional face processing than youth with unipolar depression. Almeida and colleagues hope that this type of data may eventually be used to diagnose these disorders or to measure whether treatment has been successful.

Differentiating ADHD and Bipolar Disorder

Three articles in the September 2014 issue of the journal Psychiatric Annals (Volume 44 Issue 9) discussed differentiating pediatric bipolar disorder from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The first article, by Regina Sala et al., said that reasons to suspect bipolar disorder in a child with ADHD include:

- The ADHD symptoms appear for the first time after age 12.

- The ADHD symptoms appear abruptly in an otherwise healthy child.

- The ADHD symptoms initially responded to stimulnts and then did not.

- The ADHD symptoms come and go and occur with mood changes.

- A child with ADHD begins to have periods of exaggerated elation, grandiosity, depression, decreased need for sleep, or inappropriate sexual behaviors.

- A child with ADHD has recurring severe mood swings, temper outbursts, or rages.

- A child with ADHD has hallucinations or delusions.

- A child with ADHD has a strong family history of bipolar disorder in his or her family, particularly if the child does not respond to appropriate ADHD treatments.

The second article, by this editor Robert Post, Robert Findling, and David Luckenbaugh, emphasized the greater severity and number of symptoms in childhood onset bipolar disorder versus ADHD. Children who would later develop bipolar disorder had brief and extended periods of mood elevation and decreased sleep in the early years of their lives. These, along with pressured speech, racing thoughts, bizarre behavior, and grandiose or delusional symptoms emerged differentially from age three onward. In contrast, the typical symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, and decreased attention were equal in both diagnoses.

In the third article, Mai Uchida et al. emphasized the utility of a family history of bipolar disorder as a risk factor. Moreover, a child with depression plus ADHD is at increased risk for a switch into mania on antidepressants if there is a family history of mood disorders, emotional and behavioral dysregulation, subthreshold mania symptoms, or psychosis.

The differential diagnosis of ADHD versus bipolar disorder (with or without comorbid ADHD) is critical, as drug treatment of these disorders is completely different.

Bipolar disorder is treated with atypical antipyschotics; anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, such as valproate, carbamazepine, or lamotrigine; and lithium. Only once mood is stabilized should small doses of stimulants be added to treat residual ADHD symptoms.

ADHD, conversely, is treated with short- or long-acting stimulants such as amphetamine or methylphenidate from the onset, and these may be augmented by the noradrenergic alpha-2 agonists guanfacine or clonidine. The selective noradrenergic re-uptake inhibitor atomoxetine is also approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of ADHD. The dopamine-active drug bupropion and the anti-narcolepsy drugs modafinil and armodafinil have mild anti-ADHD effects but have not been FDA-approved for that purpose.

Differentiating Bipolar Disorder and ADHD in Childhood

At the 2014 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, researcher B.N. Kim discussed symptoms that could distinguish between bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in childhood. Both disorders are characterized by decreased attention, concentration, and frustration tolerance, and increased activity, impulsiveness, and irritability.

Kim shared several differential symptoms that are more indicative of a bipolar diagnosis and that are inconsistent with a simple ADHD diagnosis (and this editor Robert Post has added several more). Signs and symptoms that suggest bipolar disorder and not ADHD include: decreased need for sleep, brief and extended periods of euphoria, hypersexuality, delusions, hallucinations, suicidal or homicidal impulses and/or actions, extreme aggression, and multiple areas of extreme behavioral dyscontrol. ADHD, on the other hand, is characterized by more difficulty focusing attention, and by less extreme symptoms in general.

Long Delays to First Treatment Are Crippling Many with Bipolar Disorder: What You Can Do

An article published by N. Drancourt et al. in the journal Acta Psychiatra Scandinavica this year examined the duration of the period between a first mood episode and treatment with a mood stabilizer among 501 patients with bipolar disorder. The time between a first episode of depression, mania, or hypomania and first treatment averaged 9.7 years. The authors conclude that more screening, better recognition of the early stages of the illness, and greater awareness are needed to decrease this long delay.

Editor’s Note: The article by Dancourt et al. replicates earlier findings of an average treatment delay of 10 years among bipolar patients from the treatment network in which this editor (Robert Post) is an investigator (formerly the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network, now called the Bipolar Collaborative Network). The duration of the untreated interval (DUP) for patients with bipolar disorder is unacceptably long and carries a heavy price.

Those with the earliest age of onset experience the longest delay to first treatment. Early onset is associated with poor outcome compared to adult onset bipolar disorder, and the duration of time untreated adds a separate, independent risk of a worse outcome in adulthood, especially more frequent and severe depression, more episodes, and less time well.

What patients and doctors can do to shorten this interval to first treatment: Know the risk factors for early onset bipolar disorder so you can seek evaluation and advise treatment as appropriate. Read more

Biomarker Panel May Help Diagnose Major Depressive Disorder

It is hoped that measuring biochemical substances in blood will help in the diagnosis of mood disorders and help direct patients to the most effective therapeutic regimens. J.L. Billbielo reported at the 51st Annual Meeting of the National Institute of Mental Health’s New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (NCDEU) in 2011 that investigators from Ridge Diagnostics in North Carolina were using this type of biomarker panel in an attempt to provide a predictive algorithm for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. The panel of 10 assays was derived from a larger screening set and included: alpha 1 antitrypsin (Alpha 1AT), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), cortisol, epidermal growth factor (EGF), resistin, and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor II (sTNFR2). The research group found that this optimized algorithm distinguished depressed subjects from normal controls with a sensitivity of approximately 90% and a sensitivity of 84%.

Editor’s note: This assay is available commercially and appears to represent an interesting panel of potential neurobiological markers of depression, including neurotrophic factors, endocrine stress hormones, and inflammatory markers. While its diagnostic utility is somewhat doubtful and must be further demonstrated, this editor hopes that similar panels could ultimately predict individual clinical response to a given treatment. For example, patients with high levels of inflammatory markers might respond better to treatments aimed at suppressing inflammation. Read more

Childhood Bipolar Disorder Still Poorly Treated

Kathleen Merikangas of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) gave a plenary presentation on developmental manifestations of the bipolar spectrum at the 2011 Pediatric Bipolar Disorder Conference in Cambridge, Massachusetts this past March, which was sponsored by Massachusetts General Hospital and the Ryan Licht Sang Foundation. There were several striking take-away messages from her epidemiological research. She found that:

- Rates of bipolar disorder in childhood were relatively similar to rates among adults

- Only 22% of youth with bipolar spectrum diagnoses actually obtained mental health treatment for their conditions

- There was no evidence that these children were being over-medicated, as some non-epidemiological reports had suggested

She also reported that those with subthreshold bipolar spectrum disorders, i.e. those not meeting strict criteria for BP-I (including full-blown mania) or BP-II (including hypomania for four or more days) still were very ill and had considerable disability and dysfunction.

Merikangas reported on interviews of 10,123 youth aging from 13 to 18 found in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), and found rates of illness among the youth similar to those seen in adults. However, these children with bipolar spectrum disorders were more than ten times more likely to be on antidepressants than mood stabilizers, and more than four times more likely to be on antidepressants than atypical antipsychotics, again suggesting these children were not receiving the treatments recommended by consensus guidelines.