Short Telomeres Associated with Family Risk of Bipolar Disorder

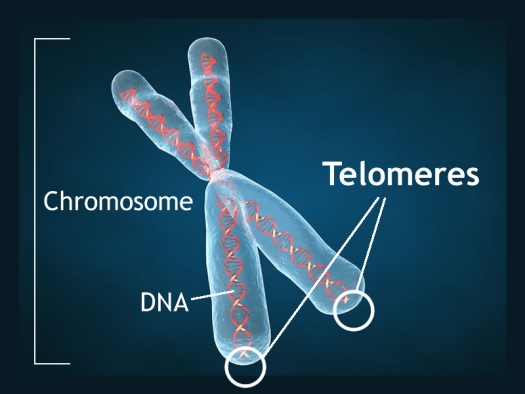

Telomeres are bits of genetic material at the end of each strand of DNA that protect chromosomes as they replicate. Short telomeres have been linked to aging and a variety of medical and psychiatric diseases. Stress and depressive episodes can shorten telomeres, while treatment with lithium can lengthen them.

Telomere length is a heritable trait, and a 2017 study by researcher Timothy R. Powell and colleagues suggests that shorter telomeres are a familial risk factor for bipolar disorder.

The study, published in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, compared the telomere lengths of 63 people with bipolar disorder, 74 of their immediate relatives (49 of whom had no lifetime psychiatric illness, while the other 25 had a different mood disorder), and 80 unrelated people with no psychiatric illness. The well relatives of the people with bipolar disorder had shorter telomeres than the unrelated healthy volunteers.

Relatives (both well and not) and people with bipolar disorder who were not being treated with lithium both had shorter telomeres than people with bipolar disorder who were being treated with lithium.

Another finding was that longer telomeres were linked to greater volume of the left and right hippocampus, and improved verbal memory on a test of delayed recall. This study provides more evidence that taking lithium increases the volume of the hippocampus and has neuroprotective benefits for people with bipolar disorder.

More News About Genetic Risk for Bipolar Disorder

In a 2017 article in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, researcher Paul E. Croarkin and colleagues describe findings from their study of genetic risk factors for early-onset bipolar disorder. The researchers focused on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which are variations in a single base pair of a DNA sequence. SNPs are normal variations or copying errors that occur when DNA is replicated. Croarkin and colleagues tracked 8 SNPs that had been linked to bipolar disorder in previous studies. They examined 69 patients from a study of early-onset mania, 732 adult patients with bipolar disorder (including 192 with early-onset illness), and 776 healthy controls. The researchers compared patients with early-onset illness to controls, and also looked for connections between specific SNPs and early-onset illness.

The SNPs analyzed in the study map to three genes that have repeatedly been associated with the risk for bipolar disorder in other studies. These include CACNA1C (one of several genes that create calcium channels), ANK3, and ODZ4. Croarkin and colleagues determined that the presence of these SNPs, particularly the ones that involved the CACNA1C gene, were associated with early-onset bipolar disorder.

Editor’s Note: These findings may lead to better treatment for early-onset bipolar disorder. The CACNA1C calcium influx gene that has repeatedly been connected to bipolar illness can be blocked by the calcium channel blocker nimodipine. Nimodipine has lithium-like effects in mania and depression in adults. One case report by Pablo A. Davanzo in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology described success using nimodipine and the thyroid medication levothyroxine to treat a 13-year-old boy with very rapid cycling bipolar disorder that had previously failed to respond to multiple medications.

Nimodipine deserves further study in children showing symptoms of bipolar disorder. The company Genomind provides testing for the CACNA1C gene. We hope it will soon be determined whether the presence of this SNP predicts a good response to nimodipine.

Being able to predict who will get bipolar disorder is a long way off. However, there are some clear risk factors. Young people from families that have had several generations of bipolar disorder or related disorders are at increased risk for bipolar disorder. This risk increases for children who experience adversity in childhood, such as abuse or neglect. The presence of early mild symptoms of mania, depression, or disruptive behavior further increase this risk.

For doctors, a patient’s clinical history of these three types of risk factors can help identify whether they are at increased risk of developing bipolar disorder. Patients with several risk factors should be observed closely and treated with psychotherapy or medication as needed.

Parents of children between the ages of 2 and 12 who have shown some signs of mood or behavioral symptoms are encouraged to join our Child Network. We provide a secure online platform where parents record their children’s symptoms of anxiety, depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional behavior, and mania on a weekly basis. Symptoms are charted over time in a graphical depiction that can be shared with the child’s doctor. For more information, see page 11 of this issue. To join, visit our website bipolarnews.org and click on the tab for the Child Network.

Parents’ History of Mood and Anxiety Disorders Increases Risk of These Disorders in Offspring

A 2016 article by researcher Petra J. Havinga and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry suggests that offspring of a parent with a mood or anxiety disorder are at higher risk for these disorders than offspring from non-ill parents. Havinga and colleagues studied 523 offspring of parents with one of these disorders. Among these offspring, 38.0% had had a mood or anxiety disorder by age 20, and 64.7% had had such a disorder by age 35. (Rates of these disorders in the general population are closer to 10%.)

The risk of offspring developing one of these disorders was even higher when both parents had a history of a mood or anxiety disorder, when a parent had an early onset of one of these illnesses, and when the offspring was female. The good news is that balanced family functioning had a protective effect, reducing the likelihood that the offspring would develop a mood or anxiety disorder.

Researcher David Axelson reported in a 2015 study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry that approximately 74% of the offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder went on to have a major psychiatric diagnosis over 6.7 years of followup. Similarly, researcher Myrna Weissman and colleagues reported in 2006 that the same high incidence of psychiatric diagnoses was true of the offspring of a parent with unipolar depression over 20 years of followup.

Editor’s Note: It is important to be vigilant for mood or behavioral disorders that may emerge in the offspring of a parent with a mood or anxiety disorder. Children at high risk should maintain a healthy diet and good sleep hygiene, exercise regularly, and perhaps try practicing mindfulness and meditation, as recommended by researcher Jim Hudziak. Family-focused therapy (developed by researcher David Miklowitz) can help when early symptoms appear in the offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder.

Another option is joining our Child Network, a secure online program that allows parents to track their children’s symptoms of anxiety, depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional behavior, and mania. This may facilitate earlier recognition and treatment of dysfunctional symptoms, which can be treated with psychotherapy and medication.

Recent Birth Cohorts May Have More Depression and Bipolar Disorder

In medicine, the ‘cohort effect’ describes the idea that more recent birth cohorts have an increased incidence and younger age of onset of their illness. A 2016 article by this editor (Robert M. Post) and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry presented evidence that younger patients with bipolar disorder have an earlier age of onset of bipolar disorder and more relatives with mood disorders than older patients with bipolar disorder.

The research was carried out by the Bipolar Collaborative Network in four US cities (Dallas, Cincinatti, Los Angeles, and Bethesda) and three northern European ones (Utrecht, Freiburg, and Munich). On both continents, patients born more recently had an earlier age of onset of their bipolar disorder. Younger patients also had parents and grandparents with a greater incidence of depression, bipolar disorder, and alcohol and substance abuse compared to older patients.

Editor’s Note: Other researchers have found evidence of a cohort effect for unipolar depression, substance abuse, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The data indicate that childhood onset of psychiatric illnesses may be becoming more common. Research aimed at earlier detection and treatment is needed to reverse these trends.

In Rats, Mother’s Exercise Habits Affect Those of Offspring

A recent study suggests that when a mother rat exercises during pregnancy, her offspring will exercise more too.

A recent study suggests that when a mother rat exercises during pregnancy, her offspring will exercise more too.

In the study, published by Jesse D. Eclarinel and colleagues in The FASEB Journal, pregnant mother rats were placed in cages that each contained an exercise wheel. One group had access to a working wheel on which they could run. The other group had the same wheel, but it was locked so that they couldn’t use it for running. Daughters of the rats who ran during pregnancy ran more in adulthood (both at 60 days and 300 days after birth) than daughters of the rats who couldn’t run during pregnancy.

While it is a mystery why this occurs, it is consistent with other data about the ways that a parent’s experiences can influence the next generation, even when the offspring don’t grow up with the parents.

For example, father rats conditioned to associate a specific smell with fear of an electric shock have offspring that also fear that smell (but not other smells).

Drug use is another example. Father rats given access to cocaine have offspring that are less interested in cocaine. Interestingly, father rats exposed to marijuana have offspring that are more interested in opiates.

Experiences with drugs or stress are thought to affect the next generation via ‘epigenetic’ marks on ova or sperm. These marks change the way DNA is packaged, with long-lasting effects on behavior and chemistry. Most marks from a mother’s or father’s experiences are erased at the time of conception, but some persist and affect the next generation.

The nature versus nurture debate is getting more and more complicated. Parents can influence offspring in a number of ways: 1) genetics; 2) epigenetics in the absence of contact between parent and offspring after birth; 3) epigenetic effects of behavioral contact—that is, parents’ caring and warmth versus abuse and neglect can affect offspring’s DNA expression too. All these are in addition to any purely behavioral influence a parent may have on their offspring via discipline, teaching, being a role model, etc.

Editor’s Note: The moral of the story is, choose your parents wisely, or behave wisely if you yourself become a parent.

Father’s Age, Behavior Linked to Birth Defects

For decades, researchers have known that a pregnant mother’s diet, hormone levels, and psychological state can affect her offspring’s development, altering organ structure, cellular response, and gene expression. It is now becoming clear that a father’s age and lifestyle at the time of conception can also shape health outcomes for his offspring.

Older fathers have offspring with more psychiatric disorders, possibly because of increased incidence of mutations in sperm.

A 2016 article by Joanna Kitlinska and colleagues in the American Journal of Stem Cells reviewed findings from human and animal studies about the links between fathers’ behaviors and their offspring’s development.

Father’s behavior can shape gene expression through a phenomenon described as epigenetics. Epigenetics refers to environmental influences on the way genes are transcribed. While a father’s behavior is not registered in his DNA sequences, it can influence the structure of his DNA or the way in which it is packaged.

Kitlinska suggests that these types of findings should eventually be organized into recommendations for prospective parents. More research is also needed into how maternal and paternal influences interact with each other.

Some findings from the article:

- A newborn can have fetal alcohol spectrum disorder even if the mother doesn’t drink. “Up to 75% of children with [the disorder] have biological fathers who are alcoholics,” says Kitlinska.

- Father’s alcohol use is linked to low birth weight, reduced brain size, and impaired cognition.

- Dad’s obesity is linked to enlarged fat cells, diabetes, obesity, and brain cancer in offspring.

- A limited diet in a father’s early life may reduce his children and grandchildren’s risk of death from cardiovascular causes.

- Dad’s advanced age is correlated with higher rates of schizophrenia, autism, and birth defects in his children.

- Psychosocial stress on dads can affect their children’s behavioral traits.

Inflammation Linked to Bipolar Illness in Young People

The Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study, or COBY, has been collecting information on young people with bipolar disorder and tracking their symptoms into adulthood since 2000. A 2015 study by Benjamin I. Golstein in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry analyzed COBY data, identifying links between higher than average levels of inflammatory markers measured in the blood and participants’ histories of illness and familial risk factors.

The Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study, or COBY, has been collecting information on young people with bipolar disorder and tracking their symptoms into adulthood since 2000. A 2015 study by Benjamin I. Golstein in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry analyzed COBY data, identifying links between higher than average levels of inflammatory markers measured in the blood and participants’ histories of illness and familial risk factors.

High levels of the inflammatory marker hsCRP were associated with longer duration of illness, substance use disorder, and family history of suicide attempts or completed suicides. High levels of TNF-alpha were linked to suicide attempts, self-injury behaviors, and family history of substance use disorders. IL-6 was also linked to family history of substance use disorders.

There were also links between inflammatory markers and participants’ symptoms over the 6 months leading up to the blood tests. Levels of the inflammatory marker TNF-alpha were linked to the percentage of weeks patients had psychotic symptoms. Levels of IL-6 were associated with percentage of weeks with subthreshold mood symptoms and also with any suicide attempt. Levels of HsCRP were linked to maximum severity of depressive symptoms.

It is possible that targeting the elevated levels of inflammatory markers with anti-inflammatory treatments could improve patients’ response to treatments, but this topic requires further study.

Guanfacine Improves ADHD Symptoms and Academic and Social Functioning in Children

A study by researcher J.H. Newcorn and colleagues published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in 2013 found that eight weeks of treatment with the drug guanfacine (extended release) improved symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in North American children compared to placebo. A 2015 study by M.A. Stein and colleagues in the journal CNS Drugs extended this research, determining that guanfacine also improved academic and social functioning, including family dynamics, in the same group of children.

Children aged 6–12 who had been diagnosed with ADHD received either placebo or 1 to 4 mg of guanfacine extended release either in the morning or evening. The children in both guanfacine groups showed improvements in family interactions, learning and school, social behavior, and risky behavior compared to those taking placebo. No improvements were seen in life skills or self-concept. The improvements in functioning were linked to the drug’s effectiveness in improving ADHD symptoms. Those children whose ADHD symptoms improved on guanfacine were also more likely to see improvements in academic and social functioning.

Stimulants Linked to Psychotic Symptoms in Offspring of Parents with Psychiatric Illness

Stimulants are one of the most common medications prescribed to children and adolescents, typically for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In children of parents with major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia, stimulant use may come with a risk of psychotic symptoms. A 2016 study by L.E. MacKenzie and colleagues in the journal Pediatrics reported that among children and youth whose parents had one of these psychiatric illnesses, 62.5% of those who had taken stimulants had current psychotic symptoms, compared to only 27.4% of those who had not taken stimulants. The participants with psychotic symptoms tended to have hallucinations that occurred while they were taking stimulants. Doctors may want to consider whether parents have a history of psychiatric illness when deciding whether to prescribe stimulants to children and adolescents with ADHD. Activation is a common side effect of antidepressants in children who have a parent with bipolar disorder. Young people taking stimulants for ADHD should be monitored for psychotic symptoms, particularly if they have a parent with a history of depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia.

Offspring of Parents with Psychiatric Disorders At Increased Risk for Disorders of Their Own

At a symposium at the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorder, researcher Rudolph Uher discussed FORBOW, his study of families at high risk for mood disorders. Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and severe depression are at higher risk for a variety of illnesses than offspring of healthy parents.

Uher’s data came from a 2014 meta-analysis by Daniel Rasic and colleagues (including Uher) that was published in the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin. The article described the risks of developing mental illnesses for 3,863 offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression compared to offspring of parents without such disorders.

Previous literature had indicated that offspring of parents with severe mental illness had a 1-in-10 likelihood of developing a severe mental illness of their own by adulthood. Rasic and colleagues suggested that the risk may actually be higher—1-in-3 for the risk of developing a psychotic or major mood disorder, and 1-in-2 for the risk of developing any mental disorder. An adult child may end up being diagnosed with a different illness than his or her parents.

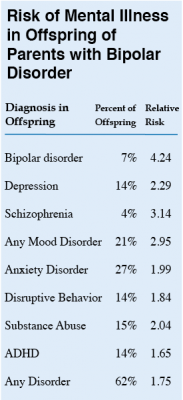

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

Editor’s Note: These data emphasize the importance of vigilance for problems in children who are at increased risk for mental disorders because they have a family history of mental disorders. One way for parents to better track mood and behavioral symptoms is to join our Child Network.