Clinical Risk Prediction in Youth at Risk for Bipolar Spectrum Disorder and Relapse

Researchers from two 15-year studies of bipolar youth, COBY (The Coarse and Outcome of Bipolar Youth Study) and BIOS (Bipolar Offspring Family Study), have used the longitudinal data from their studies in order to create a risk calculator that can predict an individual’s likelihood of illness.

At the 2020 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, researcher Danella Hafeman presented research on a risk calculator that predicts the 5-year risk for onset of a bipolar disorder spectrum diagnosis (BPSD) in young people at high risk and can reasonably distinguish those who will receive a diagnosis from those who will not.

Some of the factors used in the risk calculator include dimensional measures of mania, depression, anxiety, and mood lability; psychosocial functioning; and the age at which parents were diagnosed with a mood disorder.

Hafeman reported that there was a 25% risk that offspring of a bipolar parent would develop a bipolar disorder spectrum diagnosis. In a population ranging in age from 6 to 18 years, Hafeman and colleagues found that anxiety and depression symptoms were a sign of vulnerability to a bipolar spectrum disorder, while subthreshold manic symptoms indicated that a bipolar spectrum disorder could soon emerge. Sudden or exaggerated changes in mood were also an important predictor of BPSD.

Hafeman and colleauges noted that even in children as young as 2 to 5 years old, there were already signs of anxiety, aggression, attention problems, depression, and sudden mood changes in those who would go on to receive a diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorder.

The researchers were also able to predict which patients with BPSD would have a relapse. According to Hafeman and colleagues, “The most influential recurrence risk factors were shorter recovery lengths, younger age at assessment, earlier mood onset, and more severe prior depression.”

Editor’s Note: Offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder are at high risk for anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder, and bipolar disorder. Parents should be alert for the symptoms of these illnesses and seek evaluation and treatment for their children as necessary. Parents should also be aware of the risk factors above that contributed to the risk calculator.

Parents can aid physicians in their evaluation by joining our Child Network and keeping weekly ratings of their children’s symptoms of depression, anxiety, ADHD, oppositional behavior, and mania.

Predicting Onset of Bipolar Disorder in Children at High Risk: Part I

At the 2019 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, one symposium was devoted to new research on predicting onset of bipolar disorder in children who have a family history of the disorder. Below are some of the findings that were reported.

At the 2019 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, one symposium was devoted to new research on predicting onset of bipolar disorder in children who have a family history of the disorder. Below are some of the findings that were reported.

Symptom Progression

In offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, researcher Anne Cecilia Duffy found that symptoms in the children tended to progress in a typical sequence. Childhood sleep and anxiety disorders were first to appear, then depressive symptoms, then bipolar disorder.

Different Types of Illness May Respond Best to Different Medications

Duffy’s research also suggested links between illness features and a good response to specific medications. Those offspring who developed a psychotic spectrum disorder responded best to atypical antipsychotic medication. Those with classical episodic bipolar I disorder responded well to lithium, especially if there was a family history of lithium responsiveness. Those offspring with bipolar II (and anxiety and substance abuse) responded well to anticonvulsant medications.

If parents with bipolar disorder had experienced early onset of their illness, their children were more likely to receive a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

The offspring of lithium-responsive parents tended to be gifted students, while those from lithium non-responders tended to be poorer students.

Comparing Risk Factors for Bipolar Disorder and Unipolar Depression

Researcher Martin Preisig and colleagues also showed that parental early onset of bipolar disorder (before age 21) was a risk factor for the offspring receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Parental oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) was also a risk factor for bipolar disorder in the offspring. The emergence of depression, conduct disorder, drug use, and sub-syndromal hypomanic symptoms also predicted the onset of mania during childhood.

Conversely, sexual abuse and witnessing violence were strong risk factors associated with a diagnosis of major (unipolar) depressive disorder. Being female and experiencing separation anxiety were also factors that predicted unipolar depression.

Predicting Conversion to Mania

Researcher Danella M. Hafeman reported that mood swings (referred to in the literature as “affective lability”), depression/anxiety, and having a parent who had an early onset of bipolar disorder were linked to later diagnoses of mania. Immediate risk factors that predicted an imminent onset of mania included affective lability, substance abuse, and the presence of sub-threshold manic symptoms.

Hormone Replacement With Estrogen/Progestogen Combo Increases Breast Cancer Risk More Than Once Thought

A 2016 article in the British Journal of Cancer suggests that previous studies underestimated breast cancer risk in women who received hormone replacement therapy with the combination of estrogen and progestogen. The article by researcher Michael E. Jones and colleagues reported that combined hormone replacement therapy could increase the risk of breast cancer by more than three times, depending on how long a woman is exposed to the therapy. The longer the duration of use, the greater the risk of breast cancer. In the study, women who used other types of hormone replacement therapy, such as estrogen only or tibolone, did not have drastically higher rates of breast cancer than had been reported before.

Jones and colleagues suggest that previous studies did not use long enough follow-up periods to track whether women developed breast cancer while using hormone replacement. Their own study is based on a United Kingdom dataset known as the Breakthrough Generations Study. Study participants completed questionnaires at 2.5 years after recruitment, again at around 6 years, and again around 9.5 years. At the time of recruitment, women using combination hormone replacement therapy had been doing so for a median of 5.5 years.

Women who used combination hormone replacement therapy for 5.4 years were 2.74 times likelier to have breast cancer than those who didn’t receive hormone replacement. Using the combined therapy for more than 15 years increased risk 3.27 times compared to non-users.

The study also reported that as body mass index increased, breast cancer risk increased, regardless of hormone use.

While the study by Jones and colleagues was large (39,183 participants), the number of women who took combined hormone replacement and developed breast cancer was still fairly small (52). Seven of the 52 had taken the combined pill for more than 15 years. One limitation of this study is that these seven women may have skewed the risk assessments somewhat.

Experts suggest that women balance the possible risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy. The therapy can be helpful in reducing symptoms of menopause, particularly hot flashes.

Using the lowest effective dose for the shortest time possible may be the best option. The increased risk of breast cancer drops after a woman stops using hormone replacement.

Women with History of Depression 20 Times More Likely To Have Postpartum Depression

A study of almost all women who gave birth in Sweden between 1997 and 2008 reports that women with a history of depression are 21.03 times more likely to suffer from postpartum depression than those without such a history. The 2017 article by Michael E. Silverman and colleagues in the journal Depression and Anxiety reports that advanced age and gestational diabetes also increased the likelihood of postpartum depression.

A study of almost all women who gave birth in Sweden between 1997 and 2008 reports that women with a history of depression are 21.03 times more likely to suffer from postpartum depression than those without such a history. The 2017 article by Michael E. Silverman and colleagues in the journal Depression and Anxiety reports that advanced age and gestational diabetes also increased the likelihood of postpartum depression.

Whether a woman had gone through a depression in the past also affected her other risk factors for postpartum depression. Among women who had been depressed before, having diabetes before pregnancy and having a “mild” pre-term delivery were risk factors for postpartum depression. In contrast, among women with no history of depression, young age, having an instrument-assisted or caesarean delivery, and “moderate” pre-term delivery were risk factors for postpartum depression.

Rates of postpartum depression decreased one month after delivery.

Editor’s Note: About one in five women in the general population experience postpartum depression. All new mothers should be screened for postpartum depression, but especially those with a history of depression. Instituting supportive measures may help prevent an episode.

SSRI Use During Pregnancy Linked to Adolescent Depression in Offspring

A 2016 article by Heli Malm and colleagues in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry suggests that in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants may increase the risk of depression in adolescence. However, the study included potentially confounding factors. It is possible that women who took SSRIs during pregnancy had more severe depression than those who went unmedicated during pregnancy. The mothers in the study who took SSRIs also had more comorbid conditions such as substance abuse.

Editor’s Note: Women should balance the risks and benefits of antidepressant use during pregnancy, since depression itself can have adverse effects on both mother and fetus. It has recently been established that SSRI use during pregnancy does not cause birth defects, so women with depression that has not responded to non-pharmaceutical interventions such as psychotherapy, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, exercise, mindfulness, and repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) may still want to consider SSRIs.

Offspring of Parents with Psychiatric Disorders At Increased Risk for Disorders of Their Own

At a symposium at the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorder, researcher Rudolph Uher discussed FORBOW, his study of families at high risk for mood disorders. Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and severe depression are at higher risk for a variety of illnesses than offspring of healthy parents.

Uher’s data came from a 2014 meta-analysis by Daniel Rasic and colleagues (including Uher) that was published in the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin. The article described the risks of developing mental illnesses for 3,863 offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression compared to offspring of parents without such disorders.

Previous literature had indicated that offspring of parents with severe mental illness had a 1-in-10 likelihood of developing a severe mental illness of their own by adulthood. Rasic and colleagues suggested that the risk may actually be higher—1-in-3 for the risk of developing a psychotic or major mood disorder, and 1-in-2 for the risk of developing any mental disorder. An adult child may end up being diagnosed with a different illness than his or her parents.

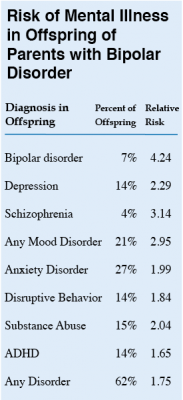

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

Editor’s Note: These data emphasize the importance of vigilance for problems in children who are at increased risk for mental disorders because they have a family history of mental disorders. One way for parents to better track mood and behavioral symptoms is to join our Child Network.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids Improve Mood and Limbic Hyperactivity in Youth with Bipolar Depression

Children who have a parent with bipolar disorder are at risk for bipolar illness, but it may first present as depression. Treating these children with antidepressants has the risk of bringing on manic episodes. Researchers are looking for treatment options for youth at risk for bipolar disorder.

Robert McNamara and colleagues found that 12 weeks of omega-3 fatty acids (2,100 mg/day) significantly improved response rates in medication-free youth ages 9–20 years compared to placebo (64% versus 36%). Omega-3 fatty acids but not placebo also reduced the activation of limbic structures in the brain (the left parahippocampal gyrus) in response to emotional stimuli.

Editor’s Note: These data add to the literature on the positive effects of 1–2 grams of omega-3 fatty acids in depression. Given the safety of omega-3 fatty acids and the ambiguous effects of antidepressants in bipolar depression, omega-3 fatty acids would appear to a good alternative, especially since the FDA-approved atypical antipsychotics (quetiapine and lurasidone) are not approved for bipolar depression in people under age 18.