Parents’ History of Mood and Anxiety Disorders Increases Risk of These Disorders in Offspring

A 2016 article by researcher Petra J. Havinga and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry suggests that offspring of a parent with a mood or anxiety disorder are at higher risk for these disorders than offspring from non-ill parents. Havinga and colleagues studied 523 offspring of parents with one of these disorders. Among these offspring, 38.0% had had a mood or anxiety disorder by age 20, and 64.7% had had such a disorder by age 35. (Rates of these disorders in the general population are closer to 10%.)

The risk of offspring developing one of these disorders was even higher when both parents had a history of a mood or anxiety disorder, when a parent had an early onset of one of these illnesses, and when the offspring was female. The good news is that balanced family functioning had a protective effect, reducing the likelihood that the offspring would develop a mood or anxiety disorder.

Researcher David Axelson reported in a 2015 study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry that approximately 74% of the offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder went on to have a major psychiatric diagnosis over 6.7 years of followup. Similarly, researcher Myrna Weissman and colleagues reported in 2006 that the same high incidence of psychiatric diagnoses was true of the offspring of a parent with unipolar depression over 20 years of followup.

Editor’s Note: It is important to be vigilant for mood or behavioral disorders that may emerge in the offspring of a parent with a mood or anxiety disorder. Children at high risk should maintain a healthy diet and good sleep hygiene, exercise regularly, and perhaps try practicing mindfulness and meditation, as recommended by researcher Jim Hudziak. Family-focused therapy (developed by researcher David Miklowitz) can help when early symptoms appear in the offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder.

Another option is joining our Child Network, a secure online program that allows parents to track their children’s symptoms of anxiety, depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional behavior, and mania. This may facilitate earlier recognition and treatment of dysfunctional symptoms, which can be treated with psychotherapy and medication.

Offspring of Parents with Psychiatric Disorders At Increased Risk for Disorders of Their Own

At a symposium at the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorder, researcher Rudolph Uher discussed FORBOW, his study of families at high risk for mood disorders. Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and severe depression are at higher risk for a variety of illnesses than offspring of healthy parents.

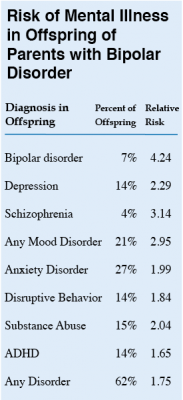

Uher’s data came from a 2014 meta-analysis by Daniel Rasic and colleagues (including Uher) that was published in the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin. The article described the risks of developing mental illnesses for 3,863 offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression compared to offspring of parents without such disorders.

Previous literature had indicated that offspring of parents with severe mental illness had a 1-in-10 likelihood of developing a severe mental illness of their own by adulthood. Rasic and colleagues suggested that the risk may actually be higher—1-in-3 for the risk of developing a psychotic or major mood disorder, and 1-in-2 for the risk of developing any mental disorder. An adult child may end up being diagnosed with a different illness than his or her parents.

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

Editor’s Note: These data emphasize the importance of vigilance for problems in children who are at increased risk for mental disorders because they have a family history of mental disorders. One way for parents to better track mood and behavioral symptoms is to join our Child Network.

Children of Bipolar Parents Are At Risk for Depression and Bipolar Disorder

The Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study, led by Boris Birmaher of the University of Pittsburgh, investigated risk of illness in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. The study included 233 parents with bipolar disorder and 143 controls. In addition to bipolar disorder, parents in the study had many other disorders, including anxiety (70%), panic (40%), a disruptive behavior disorder (35%), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD (25%), and substance use disorder (35%).

The offspring averaged age 12 at entry in the study. Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder had more illness than those of control parents, including bipolar spectrum disorders (10.6% versus 0.8%), depression (10.6% versus 3.6%), anxiety disorder (25.8% versus 10.8%), oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder (19.1% versus 8.0%), and ADHD (24.5% versus 6.7%). Of these differences, only bipolar spectrum disorders and anxiety were statistically significant after correcting for differences in the parents’ other diagnoses.

Two factors predicted bipolar spectrum disorders in the offspring: younger age of a parent at birth of child and bipolar disorder in both parents. Older children and those with diagnoses of anxiety or oppositional defiant disorder were more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

On long-term follow-up that continued on average until the offspring reached age 20, 23% of those participants who had a parent with bipolar disorder developed any type of bipolar disorder, versus only 1.2% of the children of controls. Of these 23%, about two-thirds had a depressive episode prior to the onset of their bipolar disorder.

Of the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who developed a bipolar spectrum illness, 12.3% developed bipolar I or II disorders, while 10.7% were diagnosed with bipolar not otherwise specified (NOS). Of those with bipolar NOS, which some consider to be sub-threshold bipolar disorder, about 45% converted to a bipolar I or II diagnosis after several years of prospective follow-up. These data, along with the finding that children with bipolar NOS are highly impaired and take more than a year on average to remit, stress the importance of vigorously treating this subtype, even if it does not meet the full threshold for bipolar I or bipolar II.

Birmaher indicated that although about 50% of the offspring of a bipolar patient had no diagnosis, the high incidence of multiple psychiatric difficulties developing over childhood and adolescence spoke to the importance of attempts at early intervention and prevention. Studies of effective treatment and prevention strategies are desperately needed. So far only family focused therapy (FFT), an intervention developed by researcher David Miklowitz, has shown significant benefits over standard treatment in children with a positive family history of bipolar disorder who already have a diagnosis of anxiety, depression, or bipolar not otherwise specified.