Three-Minute ‘Theta Burst’ Treatment as Effective as 37-Minute RTMS

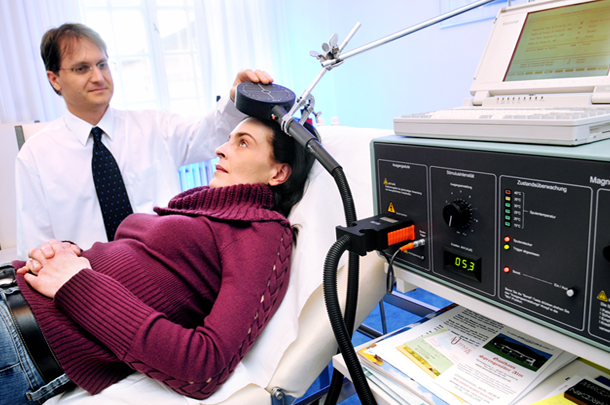

A variation on repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) called intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS) may be able to deliver the same benefits in a tenth of the time. RTMS is a non-invasive treatment in which a magnetic coil placed near the skull transmits electrical signals to the brain. It is effective in depression and has been shown to improve aspects of schizophrenia, autism, and addictions as well.

A typical rTMS session lasts for 37.5 minutes and consists of high frequency (10 Hz) stimulation. Access to the treatment remains somewhat limited, so the newer form of iTBS treatment may help more people access treatment by allowing clinicians to treat more patients in a day.

The 2018 study, published by Daniel Blumberger and colleagues in the journal The Lancet, compared iTBS to standard rTMS and evaluated the effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of the new treatment compared to the old. 414 patients aged 18–65 with major depression that had persisted despite treatment with several antidepressant options were randomized to receive either iTBS or rTMS delivered to their left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. They received the given treatment five days/week for four to six weeks.

Patients who received iTBS showed a nearly identical level of improvement in depression to those who received rTMS. Self-reports of pain intensity were worse among those who received iTBS, but the dropout rate was not higher for that group. Headaches were the most common side effect reported, and rates were similar across both groups. The authors judged iTBS to be a comparable, non-inferior alternative to rTMS for people with major depression.

Among participants who received iTBS, depression improved significantly, with 32 percent reporting a remission of depression symptoms. Those who received standard rTMS had a remission rate of 27 percent.

Psychoeducation Is a Must for Bipolar Disorder

In 2018, researcher S.A. Soo and colleagues published a systematic review in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry that analyzed findings from 40 randomized studies of psychoeducation for the management of bipolar disorder and compared the results for different types of psychoeducation: group, family, individual, and internet-based. Most of the randomized controlled trials (28 of 40 studies, 70.0%) assessed group or family psychoeducation, which had many benefits, while studies of individual or internet-based psychoeducation tended to be inconsistent.

The findings: “Group psychoeducation was associated with reduced illness recurrences, decreased number and duration of hospitalizations, increased time to illness relapse, better treatment adherence, higher therapeutic lithium levels, and reduced stigma. Family psychoeducation was associated with reductions in illness recurrence, hospitalization rates, and better illness trajectory as well as increased caregiver knowledge, skills, support, and sense of well-being and reduced caregiver burden.”

Editor’s Note: Given these results, it appears that group or family psychoeducation is a critical component to good care. Soo and colleagues suggest that future studies should directly compare different types of psychoeducation to each other to evaluate whether specific benefits are useful at various stages of illness.

Poll Finds 87% of US Adults Think Children Need More Mental Health Support

In a poll of 2,014 adults in the US, 87% believed that children need more mental health support. For over a decade, the editors of the BNN have been emphasizing the great need for earlier recognition and treatment of children with bipolar and related mood and behavioral disorders. With so many Americans in agreement, now could be the time to direct public health and research funds to the better support of children’s mental health. Sadly this does not yet seem to be the case, but this is an election year. We need stand-up leaders in Congress to marshal the resources to increase the well-being of current and future generations.

Vortioxetine Improves Processing Speed in Depression

In May 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a label change for the antidepressant vortioxetine (Trintellix), reflecting new data that show the drug can improve processing speed, an aspect of cognitive function that is often impaired in people with depression. Vortioxetine was first approved by the FDA for the treatment of depression in 2013.

In May 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a label change for the antidepressant vortioxetine (Trintellix), reflecting new data that show the drug can improve processing speed, an aspect of cognitive function that is often impaired in people with depression. Vortioxetine was first approved by the FDA for the treatment of depression in 2013.

The approval followed eight-week double-blind placebo-controlled studies of vortioxetine’s effects on cognitive function in adults aged 18–65 who have depression. The studies were known as FOCUS and CONNECT. Patients received either 10mg/day, 20mg/day, or placebo. Those who took vortioxetine showed improvement on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, a measure of processing speed, in addition to improvement in their depression.

Editor’s Note: This is the first time the FDA has approved labeling that describes an antidepressant as improving aspects of cognition in depression. Cognition is impaired in many patients with depression, such that this component of the drug’s effects could be of clinical importance. Among the 5 serotonin (5HT) receptor effects of the drug (in addition to the traditional blockade of serotonin reuptake shared by all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (SSRIs)), it is likely that vortioxetine’s effects in blocking 5HT-3 and 5HT-7 receptors are important to the drug’s effects on processing speed.

The Gold Standard in Bipolar Disorder Treatment

Last year our Editor-in-Chief Robert M. Post participated in a symposium at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association on the best treatments for bipolar disorder. An article in Psychology Today describes some of the conclusions of the expert panel.

Treatment Approaches to Childhood-Onset Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder

Dear readers interested in the treatment of young children with bipolar disorder and multiple other symptoms: In 2017, BNN Editor Robert M. Post and colleagues published an open access paper in the journal The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders titled “A Multi-Symptomatic Child: How to Track and Sequence Treatment.” The article describes a single case of childhood-onset bipolar disorder shared with us via our Child Network, a research program in which parents can create weekly ratings of their children’s mood and behavioral symptoms, and share the long-term results in graphic form with their children’s physicians.

Here we summarize potential treatment approaches for this child, which may be of use to other children with similar symptoms.

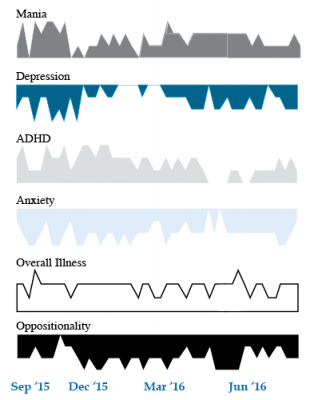

We present a 9-year-old girl whose symptoms of depression, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional behavior, and mania were rated on a weekly basis in the Child Network under a protocol approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. The girl, whose symptoms were rated consistently for almost one year, remained inadequately responsive to lithium, risperidone, and several other medications. We describe a range of other treatment options that could be introduced. The references for the suggestions are available in the full manuscript cited above, and many quotes from the original article are reprinted here directly.

As illustrated in the figure below, after many weeks of severe mania, depression, and ADHD, the child initially appeared to improve with the introduction of 4,800 micrograms per day of lithium orotate (a more potent alternative to lithium carbonate that is marketed as a dietary supplement), in combination with 1 mg per day of guanfacine, and 1 mg per day of melatonin.

Despite continued treatment with lithium orotate (up to 9,800 micrograms twice per day), the patient’s oppositional behavior worsened during the period from November 2015 to March 2016, and moderate depression re-emerged in April 2016. Anxiety was also generally less severe from December 2015 to July 2016, and weekly ratings of overall illness remained in the moderate severity range (not illustrated).

In June 2016, the patient began taking risperidone (maximum dose 1.7 mg/day) instead of lithium, and her mania improved from moderate to mild. There was little change in her moderate but fluctuating depression ratings, but her ADHD symptoms got worse.

The patient had been previously diagnosed with bipolar II disorder and anxiety disorders including school phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Given the six weeks of moderate to severe mania that the patient experienced in October and November 2015, she would meet criteria for a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder.

Targeting Symptoms to Achieve Remission

General treatment goals would include: mood stabilization prior to use of ADHD medications, a drug regimen that maximizes tolerability and safety, targeting of residual symptoms with appropriate medications supplemented with nutraceuticals, recognition that complex combination treatment may be necessary, and combined use of medications, family education, and therapy.

Mood Stabilizers and Atypical Antipsychotics to Maximize Antimanic Effects

None of the treatment options in this section are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in children under 10 years of age, so all of the suggestions are “off label.” Further, they may differ from what other investigators in this area of medicine would suggest, especially since evidence-based medicine’s traditional gold standard of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials is impossible to apply here, given the lack of research in children with bipolar disorder.

As we share in the original article, reintroducing lithium alongside risperidone could be effective, as “combinations were more effective than monotherapy in a study [by] Geller et al. (2012), especially when they involved an atypical antipsychotic such as risperidone. This might include the switch from lithium orotate to lithium carbonate,” the typical treatment for bipolar disorder, on which more research has been done. “Combinations of lithium and valproate were also more effective than either [drug alone]…in the studies of Findling et al. (2006),” and many patients needed stimulants in addition.

“Most children also needed combinations of mood stabilizers (lithium, carbamazepine, valproate) in the study [by] Kowatch et al. (2000).” In a 2017 study by Berk et al. of patients hospitalized for a first mania, randomization to lithium for one year was more effective than quetiapine on almost all outcome measures.

Targeting ADHD

“[The increased] severity of [the child’s] ADHD despite improving mania speaks to the…utility of adding a stimulant to the regimen that already includes…guanfacine,” which is a common non-stimulant treatment for ADHD. “This would be supported by the data of Scheffer et al. (2005) that stimulant augmentation for residual ADHD symptoms does not [worsen] mania, and that the combination of a stimulant and guanfacine may have more favorable effects than stimulants alone.”

However, the consensus in the field is that mood stabilization should be achieved first, before low to moderate (but not high) doses of stimulants are added. “Thus, in the face of an inadequate response to the lithium-risperidone combination in this child, stimulants could be deferred until better mood stabilization was achieved.”

Other Approaches to Mood Stabilization and Anxiety Reduction

“The anticonvulsant mood stabilizers (carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproate) each have considerable mood stabilizing and anti-anxiety effects, at least in adults with bipolar disorder. With inadequate mood stabilization of this patient on lithium and risperidone, we would consider the further addition of lamotrigine.

Lamotrigine appears particularly effective in adults with bipolar disorder who have a personal history and a family history of anxiety (as opposed to mood disorders), and it has positive open data in adolescents with bipolar depression and in a controlled study of maintenance (in teenagers 13–17, but not in preteens 10–12) (Findling et al. 2015). With better mood stabilization, anxiety symptoms usually diminish…, and we would pursue these strategies [instead of using] antidepressants for depression and anxiety in young children with bipolar disorder.”

“Carbamazepine appears to be more effective in adults with bipolar who have [no] family history of mood disorders,” unlike lithium, which seems to work better in people who do have a family history of mood disorders.

“While the overall results of oxcarbazepine in childhood mania were negative, they did exceed placebo in the youngest patients (aged 7–12) as opposed to the older adolescents (13–18) (Wagner et al. 2006).

“There are long-acting preparations of both carbamazepine (Equetro) and oxcarbazepine (Oxtellar) that would allow for all nighttime dosing to help with sleep and reduce daytime side effects and sedation. Although data [on] anti-manic and antidepressant effects in adults are stronger for carbamazepine than oxcarbazepine,” there are good reasons to consider oxcarbazepine. First, there is the finding mentioned above that oxcarbazepine worked best in the youngest children. Second, there is a lower incidence of severe white count suppression on oxcarbazepine. Third, it has less of an effect on liver enzymes than carbamazepine. However, low blood sodium levels are more frequent on oxcarbazepine than carbamazepine.

Other Atypical Antipsychotics That May Improve Depression

Playing Tackle Football Before Age 12 May Be Bad for the Brain

A 2017 study found that men who began playing American tackle football before age 12 were more likely to have depression, apathy, problems with executive functioning, and behavioral issues in adulthood than their peers who began playing football after age 12. Duration of football play did not seem to matter—those men who stopped playing football after high school were just as likely to be affected in adulthood as those who went on to play football in college or professionally.

The study by Michael L. Alosco and colleagues was published in the journal Translational Psychiatry. It included 214 men (average age 51) who had played football in their youth, but not other contact sports. The men reported their own experiences with depression, apathy, cognitive function, and behavioral regulation. Those who began football before age 12 were twice as likely to report impairment in behavioral regulation, apathy, and executive function than those who began playing later. Those who started younger were also three times more likely to have clinical depression in adulthood than those who started older.

According to Alosco and colleagues, between ages 9 and 12, the brain reaches peak maturation of gray and white matter volume, and synapse and neurotransmitter density also increases. The repeated head injuries that can occur during youth football play during this time may disrupt neurodevelopment, with lasting negative effects.

One drawback to the study was that recruitment was not random—men who volunteered for the study might have done so due to a recognition of their own cognitive problems. However, the results suggest more study is needed, and caution is encouraged when making decisions about youth football participation. Some youth football leagues have begun placing greater limits on the type of contact allowed during play.