An Inflammatory State Impedes Treatment for Bipolar Disorder

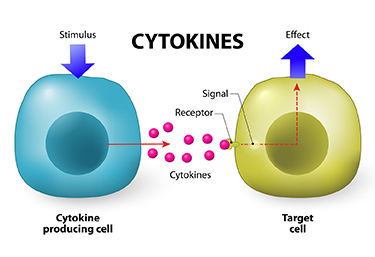

A 2017 study by in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry links inflammation to a poor antidepressant response in bipolar disorder. Many previous studies have found that elevated inflammatory markers are common in mood disorders, and that an inflammatory state seems to prevent response to certain therapies.

A 2017 study by in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry links inflammation to a poor antidepressant response in bipolar disorder. Many previous studies have found that elevated inflammatory markers are common in mood disorders, and that an inflammatory state seems to prevent response to certain therapies.

Researcher Francesco Benedetti and colleagues report that high levels of inflammatory cytokines (a type of small proteins) predicted a worse response to treatment with sleep deprivation and light therapy for bipolar depression. This treatment typically brings about a rapid antidepressant response.

Benedetti and colleagues measured 15 immune-regulating compounds in 37 patients who were experiencing an episode of bipolar depression and 24 healthy volunteers. Among those participants with bipolar disorder, 84% had a history of non-response to medication. Twenty-three of the 37 patients, or 62%, responded to the sleep deprivation/light therapy combination. Those who did not had higher levels of five cytokines: interleukin-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, interferon-gamma, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Body mass index was correlated with cytokine levels and also reduced response to the treatment.

The finding supports a link between the immune system and mood disorders. Evaluating a patient’s level of inflammation may, in the future, allow doctors to predict the patient’s response to a given therapy. Patients with high levels of inflammation might benefit most from treatments that target their immune system.

One Night of Sleep Deprivation Can Rapidly Improve Depression

One night of sleep deprivation can bring about rapid improvement in depression symptoms the following day. A 2017 meta-analysis by Elaine M. Boland and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry summarizes the findings from 66 studies of sleep deprivation for unipolar and bipolar depression and finds that the technique produced a response rate of 45% in randomized controlled studies.

One night of sleep deprivation can bring about rapid improvement in depression symptoms the following day. A 2017 meta-analysis by Elaine M. Boland and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry summarizes the findings from 66 studies of sleep deprivation for unipolar and bipolar depression and finds that the technique produced a response rate of 45% in randomized controlled studies.

It did not seem to matter whether patients experienced full or partial sleep deprivation, whether they had unipolar or bipolar depression, or whether or not they were taking medication at the time. Age and gender also did not affect the results of the sleep deprivation.

Extending the Effects

While sleep deprivation can rapidly improve depression, the patient often relapses after the next full night of sleep. There are a few things that can prevent relapse or extend the efficacy of the sleep deprivation. The first is lithium, which has extended the antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation in people with bipolar disorder.

The second strategy to prevent relapse is a phase change. This means going to sleep early in the evening the day after sleep deprivation and gradually shifting the sleep schedule back to normal. For example, after an effective night of sleep deprivation, one might go to sleep at 6pm and set their alarm for 2am. Then the next night, they would aim to sleep from 7pm to 3am, the following night 8pm to 4am, etc. until the sleep wake cycle returns to a normal schedule.

A 2002 article by P. Eichhammer and colleagues in the journal Life Sciences suggested that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), electromagnetic stimulation of the scalp over the prefrontal cortex, could help maintain improvement in depression following a night of partial sleep deprivation for up to four days.

Bright light therapy may also help. Read more

Inflammation Predicts Poor Response to Sleep Deprivation with Light Therapy

A 2017 article by Francesco Benedetti and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry reports that people with bipolar depression who have higher levels of certain inflammatory markers may have a poor antidepressant response to the combination of sleep deprivation and light therapy, compared to those with lower levels of inflammation.

The study included 37 participants with bipolar disorder who were in the midst of a major depressive episode. Of those, 31 participants (84%) had a history of poor response to antidepressant medication. The patients were treated with three cycles of total sleep deprivation and light therapy within one week, a combination that can often bring about a rapid improvement in depression.

Depression improved in a total of 23 patients (62%) following the therapy. Blood analysis showed that compared to those who had a good response, the non-responders had higher levels of five intercorrelated inflammatory markers: IL-8, MCP-1, IFN-gamma, IL-6, and TNF-alpha. Those with higher body mass index had more inflammation, indirectly decreasing response to the therapy.

Antidepressant Effects of Sleep Deprivation are Associated with Increases in BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a protein that protects neurons and aids with learning and memory. BDNF levels are low in people with depression, and every type of antidepressant treatment increases BDNF, including different types of medications, electro-convulsive therapy, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), exercise, atypical antipsychotic drugs used to treat bipolar depression, omega-3 fatty acids, and ketamine. New research shows that sleep deprivation, which is sometimes used to rapidly improve depression, also increases BDNF.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a protein that protects neurons and aids with learning and memory. BDNF levels are low in people with depression, and every type of antidepressant treatment increases BDNF, including different types of medications, electro-convulsive therapy, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), exercise, atypical antipsychotic drugs used to treat bipolar depression, omega-3 fatty acids, and ketamine. New research shows that sleep deprivation, which is sometimes used to rapidly improve depression, also increases BDNF.

A study by researcher Anne Eckert and colleagues found that partial sleep deprivation (preventing sleep only during the second half of one night) increased BDNF levels in the blood the following day. Those participants who responded well to the sleep deprivation were found to have BDNF levels that fluctuated more throughout the day before the sleep deprivation compared to participants who did not respond well to the sleep deprivation, whose BDNF levels were relatively stable.

The research, which was presented at a scientific meeting in 2015, suggests that sleep deprivation in depressed patients increases BDNF, and that such increases are an important function of any antidepressant treatment.

Rapid-Onset Antidepressant Treatments

At the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP) World Congress of Neuropsychopharmacology in 2014, several presentations and posters discussed treatments that bring about rapid-onset antidepressant effects, including ketamine, isoflurane, sleep deprivation, and scopolamine.

Ketamine’s Effects

Multiple studies, now including more than 23 according to researcher William “Biff” Bunney, continue to show the rapid-onset antidepressant efficacy of intravenous ketamine, usually at doses of 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes. Response rates are usually in the range of 50–70%, and effects are seen within two hours and last several days to one week. Even more remarkable are the six studies (two double-blind) reporting rapid onset of antisuicidal effects, often within 40 minutes and lasting a week or more. These have used the same doses or lower doses of 0.1 to 0.2mg/kg over a shorter time period.

Attempts to sustain the initial antidepressant effects include repeated ketamine infusions every other day up to a total of six infusions, a regimen in which typically there is no loss of effectiveness. Researcher Ronald Duman is running a trial of co-treatment with ketamine and lithium, since both drugs block the effects of GSK-3, a kinase enzyme that regulates an array of cellular functions, and in animals the two drugs show additive antidepressant effects. In addition, lithium has been shown to extend the acute antidepressant effects of one night of sleep deprivation, which are otherwise reversed by a night of recovery sleep.

Ketamine’s effects are related to the neurotransmitter glutamate, for which there are several types of receptors, including NMDA and AMPA. Ketamine causes a large burst of glutamate presumably because it blocks NMDA glutamate receptors on inhibitory interneurons that use the neurotransmitter GABA, causing glutamatergic cells to lose their inhibitory input and fire faster. While ketamine blocks the effects of this glutamate release at NMDA receptors, actions at AMPA receptors are not blocked, and AMPA activity actually increases. This increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is also required for the antidepressant effects of ketamine. Ketamine also increases the effects of mTOR, a kinase enzyme that regulates cell growth and survival, and if these are blocked with the antibiotic rapamycin, antidepressant effects do not occur.

In animal studies, ketamine increases dendritic spine growth and rapidly reverses the effects of chronic mild unpredictable stressors on the spines (restoring their mature mushroom shape and increasing their numbers), effects that occur within two hours in association with its rapid effects on behaviors that resemble human depression.

About 50–70% of treatment-resistant depressed patients respond to ketamine. However, about one-third of the population has a common genetic variation of BDNF in which one or both valine amino acids that make up the typical val-66-val allele are replaced with methionine (producing val-66-met proBDNF or met-66-met proBDNF). The methionine variations result in the BDNF being transported less easily within the cell. Patients with these poorly functioning alleles of BDNF are less likely to get good antidepressant effects from treatment with ketamine.

Ketamine in Animal Studies

Researcher Pierre Blier reviewed the effects of ketamine on the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. In rodents, a swim stress test is used to measure depression-like behavior. Researchers record how quickly the rodents give up trying to get out of water and begin to float instead. Blier found that ketamine’s effects on swim stress were dependent on all three neurotransmitters. For dopamine, ketamine’s effects were dependent on increases in the number of dopamine cells firing, not on the firing rate, and for norepinephrine, ketamine’s effects were dependent on increases in burst firing patterns. Each of these effects was dependent on glutamate activity at AMPA receptors. Given these effects, Blier believes that using ketamine as an adjunct to conventional antidepressants that tend to increase these neurotransmitters may add to its clinical effectiveness.

Important Anecdotal Clinical Notes

Blier reported having given about 300 ketamine infusions to 25 patients, finding that two-thirds of these patients responded, including one-third who recovered completely, while one-third did not respond to the treatment. Patients received an average of 12 infusions, not on a set schedule, but according to when they began to lose response to the last ketamine infusion. If a patient had only a partial response, Blier gave the next ketamine treatment at a faster rate of infusion and was able to achieve a better response. These clinical observations are among the first to show that more than six ketamine infusions may be effective and well tolerated. Read more