Connections Between Stress and Substance Use May Be Mediated By Corticotropin-Releasing Factor

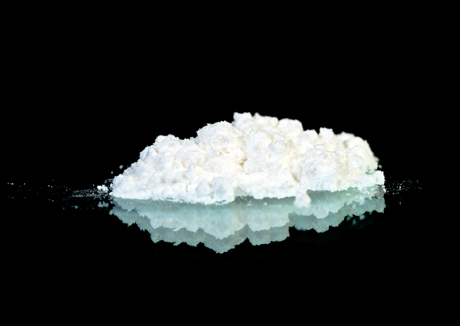

Researchers hope to map out the neurocircuitry by which stress leads to compulsive drug taking. A recent study by Klaus Miczek and colleagues examined different rodents’ responses to the stress of being repeatedly placed in the cage of a larger, more aggressive rodent, developing what is known as defeat stress, a set of behaviors that mimic human depression. Mice and rats showed increases in the stress hormone corticosterone that did not diminish over repeated run-ins with a larger animal. Rodents who were exposed to this stress became sensitized to cocaine or amphetamine, showing hyperactivity that increased each time they accessed the drug (the opposite of a tolerance response). Some also “binged” on cocaine, which they were able to self-administrate by pushing a lever to receive infusions. The mice and rats that went through the social defeat showed elevated levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, the brain’s reward center. Levels were related to the severity of their stressful experience.

Researchers hope to map out the neurocircuitry by which stress leads to compulsive drug taking. A recent study by Klaus Miczek and colleagues examined different rodents’ responses to the stress of being repeatedly placed in the cage of a larger, more aggressive rodent, developing what is known as defeat stress, a set of behaviors that mimic human depression. Mice and rats showed increases in the stress hormone corticosterone that did not diminish over repeated run-ins with a larger animal. Rodents who were exposed to this stress became sensitized to cocaine or amphetamine, showing hyperactivity that increased each time they accessed the drug (the opposite of a tolerance response). Some also “binged” on cocaine, which they were able to self-administrate by pushing a lever to receive infusions. The mice and rats that went through the social defeat showed elevated levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, the brain’s reward center. Levels were related to the severity of their stressful experience.

Later the rodents had a choice between water and a 20% alcohol solution. The researchers determined what type of stress led the rodents to consume the alcohol solution instead of the water. The maximal effect was seen in two types of mice that suffered an attack of less than five minutes that resulted in a moderate number of attack bites (30); this resulted in the mice consuming large amounts (15–30 g/kg/day) of the alcohol solution. Earlier sensitization to cocaine or amphetamine did not predict later alcohol or cocaine self-administration.

When the researchers injected the rodents with antagonists of the receptors for corticotropin-releasing factor, a hormone and neurotransmitter important in stress response, prior to each episode of social defeat, the rodents did not escalate their cocaine or alcohol self-administration, indicating that CRF plays an essential role in the process by which stress makes animals prone to using substances.

In related research by Camilla Karlsson and colleagues, IL-1R1 and TNF-1R, the receptors for two inflammatory cytokines, mediated the effects of social stress on escalated alcohol use in mice.

Oxytocin Can Block Stress-Induced Relapse of Cocaine Seeking in Animals

Stress can trigger former drug users to begin taking drugs again. In clinical trials, the bonding hormone oxytocin has been found to reduce stress-induced cravings for certain drugs, including alcohol and marijuana. A new study in animals suggests that oxytocin may be able to reduce stress-induced cocaine cravings as well.

Brandon Bentzley and colleagues combined an unpredictable shock to the foot with an alkaloid called yohimbe that comes from a particular tree bark to apply stress to animals who had previously developed a cocaine self-administration habit that had since been extinguished. The combination of the foot shocks and yohimbe brought back robust reinstatement of the animals’ cocaine seeking behaviors, but pretreatment with oxytocin (at doses of 1 mg/kg) prevented this reinstatement.

This research suggests that oxytocin has potential to prevent stress-induced cocaine cravings in people.

Maternal Childhood Adversity Associated with Low Infant Birth Weight

In a study of the effect on infant health of a mother’s experience of adversity in childhood by researcher Deborah Kim and colleagues, both adversity in childhood (such as physical abuse or the loss of a parent) and stress during pregnancy were associated with low infant birth weight and lower gestational age at birth.

Among 146 women enrolled in the study, 58.2% percent scored a 0 on the Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire (ACE), 24% scored a 1, and 17.8% scored a 2. Those who scored higher on the ACE also scored higher on a scale measuring perceived stress. A score of 2 or higher on the ACE was associated with lower gestational age at birth, indicating infants born prematurely. Greater stress during pregnancy was associated with lower gestational age at birth and lower infant birth weight. When potential confounding demographic factors were removed from the analyses, ACE scores of 2 or higher were still associated with lower infant birth weight, while perceived stress was no longer associated with either low birth weight or gestational age.

Childhood adversity is associated with increases in inflammation and multiple adverse medical consequences in adults. The researchers called childhood adversity a “significant predictor of poor delivery outcomes” for women.

Editor’s Note: This research shows that a mother’s health and earlier life stressors could have an adverse effect on her child.

Childhood adversity leaves behind a residue of neuroendocrine and neuroclinical alterations that can persist into adulthood. Many are mediated by epigenetic changes, consisting of small chemical marks that attach to DNA and the histones around which it is wrapped.

In addition to these neurobiological alterations mediated by epigenetic effects, there is new evidence that some epigenetic marks can be passed on to the next generation via a mother’s egg or a father’s sperm. Thus, either directly or indirectly, parents’ adverse life experiences can influence the health of their offspring.

Atypical Antipsychotic Lurasidone Normalizes a Gene Important in Circadian Rhythms

Disruptions to circadian rhythms are common in mood disorders, leading some researchers to believe that normalizing these daily rhythms may improve the illnesses. Several genes, called CLOCK genes, are implicated in circadian rhythms. In animal studies, researcher Marco Riva and colleagues are examining the expression of CLOCK genes in different brain regions as a result of chronic stress that is meant to produce behaviors resembling human depression.

Male rats were exposed to chronic mild stress for two weeks, and divided into those that were susceptible to stress (identified by their loss of interest in sucrose) and those who were not. Then the rats were randomized to receive either a placebo treatment or 3 mg/kg/day of the atypical antipsychotic lurasidone (trade name Latuda), which has been effective in bipolar depression, during five more weeks of the stress procedure.

The researchers observed the expression of clock genes Clock/Bmal1, Per1, Per2, Cry1, and Cry2. In susceptible rats, the chronic mild stress decreased the clock genes Per1, Per2, and Cry2 in the prefrontal cortex. Lurasidone reversed these CLOCK gene abnormalities and the rats’ depression-like behaviors, which may explain some of the drug’s efficacy in bipolar depression.

Editor’s Note: Lurasidone is also a potent inhibitor of 5HT7 serotonin receptors, an effect that has been linked to antidepressant efficacy. Lurasidone also increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is important for learning and memory, and prevents stress from decreasing BDNF. Now it seems that lurasidone’s normalization of CLOCK genes may be another mechanism that explains the drug’s antidepressant effects.

Anti-Inflammatory Treatment Prevents the Effects of Stress in Female Rats

Women are more likely than men to experience depression, and this difference begins in adolescence, when girls show more sensitivity to stress. Researchers are studying how animals react to stress in the hopes of learning what mediates these gender differences in mental illness.

At a recent scientific meeting, researcher Jodi Lukkes and colleagues presented a recent study of stress and inflammation in female rats. The rats were exposed to different types of stressors. Some were separated from their mothers for four hours a day during the first 20 days of their lives. Later, some rats were exposed to an acute stressor, witnessing another rat receiving shocks. All the rats were placed in a box in which they could escape a shock by jumping to the other end of the box, in order to measure their motivation. Because drugs that inhibit the inflammatory enzyme COX-2 had reversed the effects of maternal separation in earlier studies, the researchers also treated some rats with these anti-inflammatories.

The researchers found that anti-inflammatory treatment could prevent behavioral consequences of stress in adolescent female rats. Witnessing another rat being shocked brought about deficits in motivation (a depression-like behavior), but in rats that had received treatment with a COX-2 inhibitor, these deficits were reduced. The COX-2 treatment was only helpful to rats that had experienced an acute stressor in their lifetime, either maternal separation in infancy, or witnessing another rat receive the shocks. A history of stress was required for the anti-inflammatories to improve motivation.

Lukkes and colleagues hope that this research begins to clarify the relationship between stress, inflammation, and gender. This may eventually lead to new targets in the treatment of depression.

Transgenerational Transmission of Drug Exposure and Stress in Rodents

New data suggest that there can be transgenerational transmission of the effects of drug exposure and stress from a paternal rat to its offspring. The father mates with a female who was not exposed to drugs or stress and never has any contact with the offspring. Consensus is now building that this transmission occurs via epigenetic alterations in sperm.

Epigenetic alterations are those that are mediated by chemical changes in the structure of DNA and of the histones around which DNA is wrapped. These changes do not alter the inherited gene sequences but only alter how easy it is for genes encoded in the DNA to be activated (transcribed) or suppressed (inhibited).

There are three common types of epigenetic modifications. One involves the attachment of a methyl or acetyl group to the N-terminals of histones. Methylation typically inhibits transcription while acetylation activates transcription. Histones can also be altered by the addition of other compounds. The second major type of epigenetic change is when the DNA itself is methylated. This usually results in inhibition of the transcription of genes in that area. The third epigenetic mechanism is when microRNA (miRNA) binds to active RNA and changes the degree to which proteins are synthesized.

At a recent scientific meeting, researchers described the various ways epigenetic changes can be passed on to future generations.

Researcher Chris Pierce reported that chronic cocaine administration increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the medial prefrontal cortex of rats. (BDNF is important for learning and memory.) The cocaine administration led to acetylation of the promoter for BDNF.

This exposure to cocaine in male rats who then fathered offspring led to two changes in the offspring, presumably conveyed by epigenetic changes to the fathers’ sperm. The first change was a decrease in cocaine reinforcement. The offspring took longer to acquire a cocaine self-administration habit. The second change was long-lasting learning deficits in the male offspring, specifically recognition of novel objects. The deficit was associated with a reduction in long-term potentiation in the offspring. Long-term potentiation is the strengthening of synapses that occurs through repeated patterns of activity. Surprisingly, the following generation also showed deficits in learning and memory, but did not show a loss of long-term potentiation.

Editor’s Note: These data indicate that alterations in sensitivity to cocaine (in this case slower acquisition of cocaine self-administration) can be transferred to a later generation, as can learning deficits in males. These data suggest that fathers’ experience of drugs can influence cocaine responsiveness and learning via epigenetic mechanisms likely mediated via epigenetic changes to the father’s sperm.

This research suggests the possibility that, in a human clinical situation, there would be three ways that a father’s drug abuse could affect his child’s DNA. First, there is the traditional genetic inheritance, where, for example, an increased risk for drug abuse is passed on to the child via the father’s genetic code. Next, drug abuse brings about epigenetic changes to the father’s sperm. (His genetic code remains the same, but acetyl groups attach to the BDNF promoter section of his DNA, changing how those proteins get produced.) Lastly, if the father’s drug abuse added stress to the family environment, this stress could have epigenetic effects on the child’s DNA.

Researcher Alison Rodgers described how epigenetic changes involving miRNA in paternal rats influence endocrine responsivity to stress in their offspring. Rodgers put rats under stress and observed a decrease in hormonal corticosterone response to stress. When a father rat was stressed, nine different miRNAs were altered in its sperm. To prove that this stress response could be passed on transgenerationally via miRNAs, the researchers took sperm from an unstressed father, loaded it with one or all nine miRNAs from the stressed animal, and artificially inseminated female rats. Rodgers found that the sperm containing all nine miRNAs, but not the sperm carrying one randomly selected miRNA, resulted in offspring with a blunted corticosterone response to stress.

Researcher Eric Nestler showed that when a rodent goes through 10 days of defeat stress (being defeated repeatedly by a larger animal), they begin to exhibit behaviors resembling those seen in depression. Social avoidance was the most robust change, and continued for the rest of the animal’s life. Animals did not have to be physically attacked by the bigger animal to show the depression-like effects of defeat stress. Just witnessing the repeated defeats of another rat was sufficient to produce the syndrome. Again, father rats that experienced defeat stress or witnessed it passed this susceptibility to defeat stress on to their offspring (with whom they never had any contact), likely by epigenetic changes to sperm. Read more

Childhood Maltreatment Leads to Inflammation and Depression in Adulthood

Researcher Andrea Danese discussed the influence of childhood maltreatment on inflammation in a symposium at the 2014 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Danese indicated that inflammation is part of the normal immune system, which includes the blood brain barrier, recognition of self- versus non-self proteins, activation of cytokines and endothelial cells, and response by phagocytes and acute phase proteins. In an acute phase inflammatory response, the liver secretes proteins including c-reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen into the blood, where their levels can be measured.

Normal amounts of inflammation can be protective, while excessive or persistent inflammation can be damaging and pathological. The inflammatory cytokines interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor (TNF alpha) induce an enzyme called indoleamine oxidase (IDO) that shunts the amino acid tryptophan away from its normal path, which yields serotonin, so that it instead yields kynurenine and then kynurenic acid, which inhibits the action of glutamate at NMDA receptors. Kynurenine can also be hydroxylated and turned into quinolinic acid, which activates glutamate NMDA receptors and causes toxicity.

In addition, inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin six (Il-6) can cross the blood brain barrier and directly influence neurotransmission. Meta-analyses have shown that inflammatory markers CRP, IL-6, IL-1, and IL-1 Ra all increase significantly in depression. A direct demonstration of the relationship between inflammation and depression is the finding that when hepatitis C is treated using the inflammatory treatment interferon gamma, there is about a 30% incidence of depression, which responds to the antidepressant paroxetine.

Stress can also increase the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, driving inflammation, and decrease parasympathetic activity, resulting in further inflammation. In addition, glucocorticoid receptor resistance can develop, enhancing depression, and increasing inflammation. Thus there are multiple ways inflammation can develop.

Danese described a study from New Zealand in which 1000 participants were observed over several decades—from childhood through age 38. The small percentage of participants who experienced maltreatment as children (aged three to eleven) showed a linear increase in CRP in adulthood as a function of their histories of previous child maltreatment. The maltreatment included parental rejection in 14%, sexual abuse in 12%, harsh discipline in 10%, changing caretakers in 6%, and physical abuse in 4%. Childhood maltreatment was also associated with some unfortunate outcomes in adulthood, including lower socioeconomic status, more major depression, more persistent depression, more cardiovascular risk, and more smoking. In other studies, Danese found that compared with controls, patients with depression alone, and patients with maltreatment alone, a greater number of patients with both depression and maltreatment (about 30%) had elevated CRP.

Danese noted that in a study by Ford et al. (2004), recurrent depressions, but not single depressions, were also significantly associated with increased CRP. In a meta-analysis by Nanni et al. in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2012, Danese and colleagues found that across multiple studies, childhood maltreatment was associated with a twofold increase in the incidence of depression and a twofold increase in the persistence of depression (chronic depression or treatment resistance). The traditional optimal treatment for depression, combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, was also significantly less effective in those with histories of childhood maltreatment. However, psychotherapy alone was equally effective in those with and without childhood maltreatment.

Together these data suggest that childhood maltreatment, partly through an inflammatory pathway, results in multiple difficulties in adulthood, including depression and treatment resistance. These data speak to the importance of attempting to prevent maltreatment in the first place, and ameliorating its consequences should it occur.

Editor’s Note: In a 2014 article in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders, this editor Robert Post and colleagues reported that childhood adversity (verbal, physical, or sexual abuse) is associated with increases in medical comorbidities in adult patients with bipolar illness, and it is likely that inflammation could play a role in some of these medical conditions.

Childhood adversity, epigenetics, and hippocampal volume

At the 2014 meeting of the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology, researcher Booij reported that in humans, there is an interaction between adversity experienced during childhood, and an epigenetic variation in the short form of the serotonin transporter (5HT-T ss, or SLC6A4), which can influence hippocampal volume during depression.

Epigenetics refers to environmental influences on the way genes are transcribed. The impact of life experiences such as stress is not registered in DNA sequences, but can influence the structure of DNA or tightness of its packaging. Early life experiences, particularly psychosocial stress, can lead to the accumulation of methyl groups on DNA (a process called methylation), which generally constricts DNA’s ability to start transcription (turning on) of genes and the synthesis of the proteins the genes encode. DNA is tightly wound around proteins called histones, which can also be methylated or acetylated based on events in the environment. When histones are acetylated, meaning that acetyl groups are attached to them, DNA is wound around them more loosely, facilitating gene transcription (i.e. the reading out of the DNA code into messenger RNA, which then arranges amino acids in order to construct proteins). Conversely, histone methylation usually tightens the winding of DNA and represses transcription.

Booij followed 33 children who had experienced some form of adversity at a young age until they were 15 or 16, examining methylation of the serotonin transporter in their T cells and monocytes compared to 36 children who had not experienced adversity during childhood. He found that in children who had experienced abuse in childhood, the degree of that abuse was correlated with methylation of the serotonin transporter and was inversely related to the volume of the hippocampus, as measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Thus, child abuse yields lasting epigenetic effects (methylation of the serotonin transporter) and has anatomical consequences in teenagers, as seen in smaller hippocampi. These data parallel converse findings by Joan Luby et al. published in the journal PNAS in 2012, in which increased maternal warmth directed toward a child aged 4-7 was associated with increased volume of the hippocampus several years later.

Resilience Important for Mental Health

A symposium at the 2014 meeting of the American Psychiatric Association suggested that resilience may hold the key to healthy aging, and overcoming trauma and stress.

Resilience in Aging

Former APA president Dilip Jeste began the symposium with a discussion of successful aging. He noted the importance of optimism, social engagement, and wisdom (or healthy social attitudes) in aging. In a group of 83-year-olds, those with an optimistic attitude had fewer cardiovascular illnesses, less cancer, fewer pain syndromes, and lived longer. Those with high degrees of social engagement had a 50% increase in survival rate. Wisdom comprises skills such as seeing aging in a positive light, and having a memory that is biased toward the positive (the opposite of what happens in depression, where negatives are selectively recalled and remembered). Jeste encouraged psychiatrists to focus not just on the treatment of mental illness, but on behavioral change and the enhancement of wellbeing. He suggested asking patients not just, “How do you feel?” but instead, “How do you want to feel?”

Resilience in the Military

Researcher Dennis Charney gave a talk on resilience based on his work with people in the military, some of whom experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He cited a series of important principles that could enhance resilience. The first principle was to reframe adversity—assimilating, accepting and recovering from it. The second principle was that failure is essential to growth. The third principle was that altruism helps, as does a mission for the survivor of trauma. Charney suggested that a personal moral compass is also critical, whether this is based on religion or general moral principles. Other factors that are important for resilience include having a role model, facing one’s fears, developing coping skills, having a support network, increasing physical well-being, and training regularly and rigorously in multiple areas.

Charney and colleagues studied Navy SEALS who went through SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape) training. Those SEALS who had the highest resilience during this severe training exercise had the highest levels of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine and NPY (an antianxiety neuropeptide). NPY levels are low in people with PTSD. Charney and colleagues reasoned that giving a peptide that acted on the NPY-1 receptors intranasally (so that it could cross the blood brain barrier) might be therapeutic. In a rodent model of PTSD, the peptide prevented and reversed PTSD-like behaviors. Further clinical development of the peptide is now planned.

The Effects of Stress

Researcher Owen Wolkowitz described how stress accelerates the mental and physical aspects of aging. Telomeres are strands of DNA at the end of each chromosome that protect the DNA during each cell replication. Telomere length decreases with stress and aging. Read more

Meditation Improves Depression and Stress in Adolescents

A recent study in the UK compared students whose schools instituted the 9-week international Mindfulness in Schools Program (MiSP) curriculum to those who were taught a standard curriculum. Students at schools with MiSP were taught techniques for sustaining attention aimed at changing their thoughts, actions, and feelings.

A recent study in the UK compared students whose schools instituted the 9-week international Mindfulness in Schools Program (MiSP) curriculum to those who were taught a standard curriculum. Students at schools with MiSP were taught techniques for sustaining attention aimed at changing their thoughts, actions, and feelings.

Students who participated in MiSP training had fewer depressive symptoms immediately after the training and three months later. They also reported lower stress and greater well-being at follow-up. Those students using the techniques they learned in the program more consistently had better scores for depression, stress, and well-being than their peers who used the techniques less often. The study by Kuyken et al., which was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2013, included 522 students between the ages of 12 and 16.

Psychological well-being has been linked to better learning and performance in school, in addition to better social relationships. Researchers suggested that because this kind of mindfulness training is designed to help students deal with everyday stressors and experiences, it has benefits for all students, regardless of their level of well-being.