Methylphenidate Does Not Cause Mania When Taken with a Mood Stabilizer

Methylphenidate is an effective treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ritalin may be the most commonly recognized trade name for methylphenidate, but it is also sold under the names Concerta, Daytrana, Methylin, and Aptensio. A 2016 article in the American Journal of Psychiatry reports that methylphenidate can safely be taken by people with bipolar disorder and comorbid ADHD as long as it is paired with mood-stabilizing treatment.

Methylphenidate is an effective treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ritalin may be the most commonly recognized trade name for methylphenidate, but it is also sold under the names Concerta, Daytrana, Methylin, and Aptensio. A 2016 article in the American Journal of Psychiatry reports that methylphenidate can safely be taken by people with bipolar disorder and comorbid ADHD as long as it is paired with mood-stabilizing treatment.

The study was based on data from a Swedish national registry. Researchers led by Alexander Viktorin identified 2,307 adults with bipolar disorder who began taking methylphenidate between 2006 and 2014. Of these, 1,103 were taking mood stabilizers including antipsychotic medications, lithium, or valproate, while 718 were not taking any mood stabilizing medications.

Among those who began taking methylphenidate without mood stabilizers, manic episodes increased over the next six months. In contrast, patients taking mood stabilizers had their risk of mania decrease after beginning treatment with methylphenidate.

Viktorin and colleagues suggest that 20% of patients with bipolar disorder may also have ADHD, so it is not surprising that 8% of patients with bipolar disorder in Sweden receive a methylphenidate prescription.

Mood-stabilizing drugs can worsen attention and concentration, so methylphenidate treatment can be helpful if it can be done without increasing manic episodes. However, Viktorin and colleagues suggest that due to the risk of increasing mania, anyone given a prescription for methylphenidate monotherapy should be carefully screened to rule out bipolar disorder.

The researchers confirmed that taking methylphenidate for ADHD while taking a mood stabilizer for bipolar disorder is a safe combination.

Alterations in Amino Acids in Blood That Affect Metabolism May Help Explain Chronic Fatigue

Chronic fatigue syndrome, more recently known as myalgic encephalopathy, is a debilitating and somewhat mysterious illness. However, a 2016 article in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight suggests that low blood levels of amino acids related to oxidative metabolism, the process by which oxygen is used to make energy from sugars, may play a role in the illness. High levels of amino acids related to the breakdown of proteins were also seen.

The study by Øystein Fluge and colleagues compared blood concentrations of 20 amino acids in 200 patients with chronic fatigue and 102 healthy participants. There were shortages in 6 amino acids that fuel oxidative metabolism in those with chronic fatigue, particularly women. Men with chronic fatigue had high levels of a different amino acid related to protein catabolism, the breaking down of complex molecules, a process that releases energy.

The differences between men and women with the illness might be because men use muscle tissue as a source for amino acids, while women, who have less muscle mass, use amino acids from blood as fuel.

The changes in both sexes suggest a functional impairment in pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), an enzyme that is important for the conversion of carbohydrates into energy. If PDH fails to work and cells turn elsewhere to create energy, muscles may suddenly weaken and lactate may build up, which patients experience as a burning in their muscles after the slightest exertion.

Fluge and colleagues are cancer researchers. They stumbled into chronic fatigue research when they noticed that people with chronic fatigue who were treated for cancer with the drug rituximab saw reductions in their fatigue. Rituximab, which is also used to treat some autoimmune diseases, is a monoclonal antibody directed at B cells. When it binds, it induces cell death. The researchers hope to clarify the link between the immune system and the problems with energy metabolism they have identified in people with chronic fatigue.

Hormone Replacement With Estrogen/Progestogen Combo Increases Breast Cancer Risk More Than Once Thought

A 2016 article in the British Journal of Cancer suggests that previous studies underestimated breast cancer risk in women who received hormone replacement therapy with the combination of estrogen and progestogen. The article by researcher Michael E. Jones and colleagues reported that combined hormone replacement therapy could increase the risk of breast cancer by more than three times, depending on how long a woman is exposed to the therapy. The longer the duration of use, the greater the risk of breast cancer. In the study, women who used other types of hormone replacement therapy, such as estrogen only or tibolone, did not have drastically higher rates of breast cancer than had been reported before.

Jones and colleagues suggest that previous studies did not use long enough follow-up periods to track whether women developed breast cancer while using hormone replacement. Their own study is based on a United Kingdom dataset known as the Breakthrough Generations Study. Study participants completed questionnaires at 2.5 years after recruitment, again at around 6 years, and again around 9.5 years. At the time of recruitment, women using combination hormone replacement therapy had been doing so for a median of 5.5 years.

Women who used combination hormone replacement therapy for 5.4 years were 2.74 times likelier to have breast cancer than those who didn’t receive hormone replacement. Using the combined therapy for more than 15 years increased risk 3.27 times compared to non-users.

The study also reported that as body mass index increased, breast cancer risk increased, regardless of hormone use.

While the study by Jones and colleagues was large (39,183 participants), the number of women who took combined hormone replacement and developed breast cancer was still fairly small (52). Seven of the 52 had taken the combined pill for more than 15 years. One limitation of this study is that these seven women may have skewed the risk assessments somewhat.

Experts suggest that women balance the possible risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy. The therapy can be helpful in reducing symptoms of menopause, particularly hot flashes.

Using the lowest effective dose for the shortest time possible may be the best option. The increased risk of breast cancer drops after a woman stops using hormone replacement.

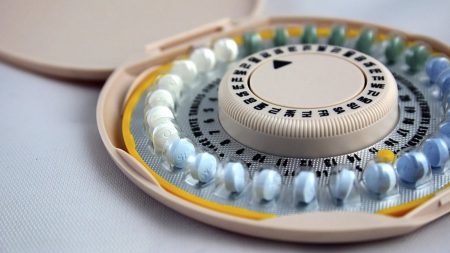

Use of Hormonal Contraceptives May Increase Depression Risk in Young Women

Women, particularly adolescent women, are at increased risk of developing depression if they use hormonal contraceptives, according to a 2016 study in the journal JAMA Psychiatry. The study by Charlotte Wessel Skovlund and colleagues used data from a Danish registry of more than one million women between the ages of 15 and 34 who had no history of depression or other psychiatric disorders. During follow-up (which lasted an average of 6.4 years), 55% of the women were using or had recently used hormonal contraceptives. These women were more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant for the first time, and more likely to be diagnosed with depression compared to women who did not use hormonal contraceptives.

The increased risk of being prescribed an antidepressant varied by contraceptive type. The norgestrolmin patch increased risk by 2.0 times, and the etonogestrel vaginal ring did so by 1.6 times. The levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) made an antidepressant prescription 1.4 times more likely. Progestin-only pills increased risk by 1.34 times and combined oral contraceptive pills increased it by 1.23 times compared to women who did not use oral contraceptives.

The relative risk peaked at around six months after starting hormonal contraceptives.

Patients aged 15–19 were particularly vulnerable to depression. The likelihood of receiving an antidepressant prescription was 1.8 times higher in teens taking combined pills, 2.2 times higher in those taking progestin-only pills, and 3 times higher in teens using hormonal methods of birth control that are not delivered orally compared to those who did not use hormonal contraceptives at all.

Women with History of Depression 20 Times More Likely To Have Postpartum Depression

A study of almost all women who gave birth in Sweden between 1997 and 2008 reports that women with a history of depression are 21.03 times more likely to suffer from postpartum depression than those without such a history. The 2017 article by Michael E. Silverman and colleagues in the journal Depression and Anxiety reports that advanced age and gestational diabetes also increased the likelihood of postpartum depression.

A study of almost all women who gave birth in Sweden between 1997 and 2008 reports that women with a history of depression are 21.03 times more likely to suffer from postpartum depression than those without such a history. The 2017 article by Michael E. Silverman and colleagues in the journal Depression and Anxiety reports that advanced age and gestational diabetes also increased the likelihood of postpartum depression.

Whether a woman had gone through a depression in the past also affected her other risk factors for postpartum depression. Among women who had been depressed before, having diabetes before pregnancy and having a “mild” pre-term delivery were risk factors for postpartum depression. In contrast, among women with no history of depression, young age, having an instrument-assisted or caesarean delivery, and “moderate” pre-term delivery were risk factors for postpartum depression.

Rates of postpartum depression decreased one month after delivery.

Editor’s Note: About one in five women in the general population experience postpartum depression. All new mothers should be screened for postpartum depression, but especially those with a history of depression. Instituting supportive measures may help prevent an episode.