Following Collisions, High School Football Players with No Signs of Concussion May Still Have Neurological Impairment

In a small 2014 study in the Journal of Neurotrauma, researcher Thomas M. Talavaga and colleagues reported that repeated head trauma that did not produce concussion symptoms was still associated with neurocognitive and neurophysiological changes to the brain in high school football players.

The longitudinal study tracked ‘collision events’ experienced by 11 teens who played football at the same high school. The young men also completed neurocognitive testing and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of their brains over time.

The researchers expected to see the participants fall into two categories: those who had no concussions and normal neurological function, and those who had at least one concussion and subsequent neurological changes. They ended up observing a third group: young men who had not exhibited concussion symptoms, but nonetheless had measurable changes to their neurological functioning, including impairments to visual working memory and altered activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Young men in this last group had had more collisions that impacted the top front of the head, directly above the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

The authors suggest that the discovery of this third category mean that some neurological injuries are going undetected in high school football players. The players who are injured in this way are not likely to seek treatment, and may continue playing football, risking more neurological brain injury or brain damage with subsequent collisions.

Repeated Sports Injuries Linked to Brain Inflammation

Professional football players face repeated mild traumatic brain injuries throughout their careers, and may face a variety of brain impairments, from depression to dementia, as a result.

A recent study by researcher Jennifer Coughlin and colleagues clarified how these impairments may be caused by repeated brain impacts. The researchers used positron emission tomography (PET) scans to observe the volume of translocator protein, a marker of brain injury and repair, in the brains of seven active or recently retired National Football League (NFL) players. Compared to healthy, athletic volunteers who were age-matched to the NFL players, the NFL players showed greater volume of translocator protein in several brain regions, including the left and right thalamus, the left and right temporal poles, and the brainstem.

It is not yet clear whether the increased volume of translocator protein is a sign of the brain’s attempts to repair itself, or whether it shows deterioration toward chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Translocator protein is also considered a marker of microglial activation, which occurs with inflammation.

High levels of translocator protein have also been seen in patients with depression and schizophrenia.

Neuropsychological Deficits After Concussion Are Correlated with White Matter Abnormalities

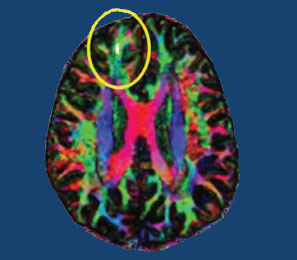

Many people suffer problems with mental functioning after an apparent concussion (otherwise known as mild traumatic brain injury, or mTBI) that does not show abnormalities on traditional brain imaging measures such as the MRI. New technology called diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) shows that the integrity of white matter tracts may be disturbed by concussions. White matter comprises parts of the brain where myelin wraps around axons, as opposed to grey matter, which reflects the presence of neuronal cell bodies.

In a longitudinal study published in the Journal of Neurotrauma, Vigneswaran Veeramuthu and colleagues compared 61 people with an mTBI to 19 healthy controls. The mTBI participants had their neuropsychological faculties assessed an average of 4.35 hours after their trauma, and participated in DTI scans an average of 10 hours after the trauma. Both the neuropsychological assessment and the DTI scan were repeated six months later. When the acute and follow-up assessments were compared to the same assessments in control participants, the two groups showed differences in numerous white matter tracts at the six-month mark. There was also an association between the degree of abnormality observed on the DTI scans and decrements in performance on the tests of neuropsychological functioning both immediately after the trauma and six months later.

The researchers concluded that their results “provide new evidence for the use of DTI as an imaging biomarker and indicator of [white matter] damage occurring in the context of mTBI, and [the results] underscore the dynamic nature of brain injury and possible biological basis of chronic neurocognitive alterations.”

Editor’s Note: People should be aware of these findings, which confirm earlier studies, and begin rehabilitative treatment as soon as possible after a concussion. New research should target white matter tract changes, with the goal of secondary prevention, i.e. limiting damage to the brain after a traumatic injury has occurred. There are several promising drugs that can prevent damage if administered immediately after an mTBI, including the antioxidant supplement N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which has shown promise in preliminary clinical and laboratory studies, and many others, including lithium and valproate, as reported by De-Maw Chuang and this editor Robert M. Post in a 2015 article in the Journal of Neurology and Stroke titled “Preventing the Sequelae of Concussions and Traumatic Brain Injury.”