Risks and Difficulties of Treating Childhood-Onset Bipolar Disorder

Early treatment is needed in childhood onset bipolar disorder

Early treatment is needed in childhood onset bipolar disorder

Multiple factors make childhood-onset bipolar disorder a difficult problem for affected children and families. Early onset is common, and treatment is often delayed or inappropriate. It takes an average of nine months to achieve remission, and relapses are common. In studies children have remained symptomatic for an average of two-thirds of the time they receive naturalistic follow up treatment, and the illness impairs social and educational development. Episodes and stressors tend to accumulate, and substance abuse is a frequent complication. Dysfunction and disability occur at a high rate among children with the illness, and suicidal ideation and acts are common.

When we surveyed adults in our treatment network, the Bipolar Collaborative Network (BCN), about the history of their illness, we found that the duration of the time lag between illness onset and first treatment was independently related to a poor outcome in adulthood. A longer delay to first treatment was associated in adulthood with greater depression severity, more days depressed, fewer days euthymic, more episodes, and more ultradian cycling (or cycling within a single day). Because treatment delay is a risk factor that can be avoided or prevented, efforts should be made to initiate treatment early in the course of bipolar illness. Read more

Maternal Smoking and Drinking Linked to ADHD in Kids with Bipolar Illness

At the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in New York in October 2010, Tim Wilens of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) presented data that maternal smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy both appeared to increase the risk of comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with bipolar disorder.

Genetic Basis for Childhood Onset of Bipolar Illness

Eric Mick of Massachusetts General Hospital reviewed the latest genetics data on bipolar disorder and reported at the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry that 20% of people with childhood-onset bipolar illness have a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder, while only 10% of those with adult-onset bipolar disorder have a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder. These data are consistent with others that indicate that there is an increased genetic/familial risk for bipolar disorder in childhood- compared with adult-onset illness.

Eric Mick of Massachusetts General Hospital reviewed the latest genetics data on bipolar disorder and reported at the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry that 20% of people with childhood-onset bipolar illness have a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder, while only 10% of those with adult-onset bipolar disorder have a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder. These data are consistent with others that indicate that there is an increased genetic/familial risk for bipolar disorder in childhood- compared with adult-onset illness.

Mick reviewed a number of findings that suggest that alterations in genes involved in intracellular signaling and in the development and maintenance of long-term memory may also be implicated in bipolar disorder. Classical genome-wide association studies (GWAS), in which a link between any human gene and bipolar disorder is sought, have not found any genes with a large effect or a high predictive value for bipolar illness. In the meantime, other strategies for finding genetic links to bipolar disorder are being pursued, including studying rare gene variants. There is some evidence that these variants occur more frequently in children with early onset bipolar illness.

Cognitive Deficits in Bipolar Children

At a symposium on new research on juvenile bipolar disorder at the meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in 2010, Ronna Fried from Massachusetts General Hospital reviewed executive function deficits that occur in children with bipolar disorder. These include difficulties in planning, working memory, response inhibition, emotional control, initiative, self-regulation, and the ability to shift focus when required.

Fried and her research group found that comorbid ADHD occurred in 69% of bipolar I children compared with 16% of controls. (ADHD involves many of the same executive function difficulties that occur in bipolar disorder—poor attention and difficulties with learning and memory.) Executive function deficits were observed in 45% of bipolar I patients compared with 17% of controls. Children with bipolar disorder who had executive function deficits had lower IQs, more difficulty reading, lower social functioning, decreased occupational functioning on long-term followup, and overall poor outcome of their illness.

Editor’s Note: These data emphasize the importance of cognitive remediation techniques in those who have major executive function deficits. Dr. Fried emphasized that rehabilitation works, and indicated its use is important for these children in order to moderate the otherwise more severe course of illness they may experience compared with those without executive function deficits.

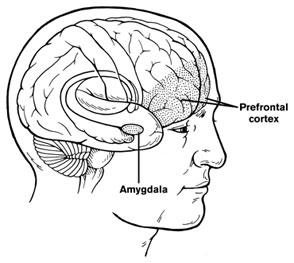

Cortex Shrinks and Amygdala Grows in Childhood Bipolar Disorder

At a symposium on new research on juvenile bipolar disorder at the meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in 2010, the discussant Kiki Chang of Stanford University reported some recent neurobiological findings on childhood bipolar disorder. He found evidence that prefrontal cortical volume appears to decrease over the course of the illness and, conversely, there was evidence of increases in amygdala volume. He also found that the volume of the striatum (or caudate nucleus, which is involved in motor control) increased in children with bipolar illness or bipolar illness comorbid with ADHD, but decreased in children with ADHD alone.

At a symposium on new research on juvenile bipolar disorder at the meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in 2010, the discussant Kiki Chang of Stanford University reported some recent neurobiological findings on childhood bipolar disorder. He found evidence that prefrontal cortical volume appears to decrease over the course of the illness and, conversely, there was evidence of increases in amygdala volume. He also found that the volume of the striatum (or caudate nucleus, which is involved in motor control) increased in children with bipolar illness or bipolar illness comorbid with ADHD, but decreased in children with ADHD alone.

Chang cited the study of Singh et al. (2010) who found that the subgenual anterior cingulate volume early in the course of illness was smaller in adolescent-onset bipolar disorder compared to controls. Given this evidence of prefrontal cortical and anterior cingulate deficits, Dr. Chang raised the possibility that treatment with lithium and other agents with potential neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects might be able to prevent these neurobiological aspects of illness progression in young patients.

Bipolar Disorder in Children Continues into Adulthood, Early Intervention Important

At a symposium on new research on juvenile bipolar disorder at the meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in 2010, researchers shared new findings about juvenile bipolar disorder. One was Kathleen Merikangas’ finding published in AACAP’s journal in 2010 that the incidence of Bipolar I and II disorders is substantial in the child population (2.6%), and most children with the illness are severely impaired. This estimate of the incidence of bipolar disorder in children approaches the 3.0% incidence of the disorder in adults.

Another finding came from Janet Wozniak of Massachusetts General Hospital. Wozniak followed children with a bipolar diagnosis longitudinally and found substantial evidence of impairment and continuity of the diagnosis over 2-3 years. She found that 73.1% of the original 78 children (aged 10.5 years at first evaluation) were still fully symptomatic with a BP-I diagnosis after 3.6 years of follow up. Only five children of the 78 achieved a euthymic status without treatment. Nine children became euthymic while on treatment, while 5 experienced subthreshold major depressive disorder and another six had subthreshold manic symptomatology.

Dr. Wozniak indicated that these data were similar to Barbara Geller’s eight-year followup study, in which patients remained symptomatic for two-thirds of the weeks of followup and 44.4% continued to show full-blown manic episodes. Researchers Barbara Geller, David Axelson, and Joe Biedermann all have found that while there is a high incidence of initial improvement or transient remission in childhood bipolar disorder, there is an equally substantial relapse rate, indicating that the considerable morbidity of childhood-onset bipolar illness continues into adolescence and young adulthood. Read more

Dosing and Efficacy of Ziprasidone in Adolescents

At the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in October 2010, Kirti Saxena of Dallas, Texas described a small pilot study that compared rapid- and slow-dose titration of ziprasidone in adolescent patients with bipolar disorder. Both slow and rapid methods of increasing doses resulted in effective treatment of acute manic symptoms, with rapid dose increases achieving improvement slightly faster.

At the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in October 2010, Kirti Saxena of Dallas, Texas described a small pilot study that compared rapid- and slow-dose titration of ziprasidone in adolescent patients with bipolar disorder. Both slow and rapid methods of increasing doses resulted in effective treatment of acute manic symptoms, with rapid dose increases achieving improvement slightly faster.

Editor’s Note: Given the data from patients with schizophrenia that higher doses of ziprasidone are better tolerated than lower doses, rapid dose titration toward 160mg/day or higher in manic patients may be best, because low doses can be associated with agitation or excitation in some patients.

If ziprasidone is being used, it is important that it is taken with food and not on an empty stomach, because its bioavailability and ability to increase blood levels is highly dependent on its being absorbed with food. The variability of ziprasidone’s effectiveness based on whether it is taken with food might explain some inconsistencies in the findings on ziprasidone in the treatment of some syndromes.

Two potential concerns about ziprasidone are worth noting. 1) It has not been approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acute mania in children or adolescents, even though the placebo-controlled trials were positive. A further review of the data by the FDA is pending. 2) The drug is associated with prolongation of the QTC interval, a measure of electrical activity in the heart. Such a prolongation theoretically predisposes patients to cardiac arrhythmias. However, in clinical follow up studies in adults and children, this has not proven to be problematic, and a study comparing 9,000 adults on olanzapine (which does not increase the QTC interval) and ziprasidone (which does) showed equal degrees of adverse cardiovascular events.

Ziprasidone is clearly worthy of consideration for treating adolescents, because it does not cause weight gain, nor does it increase any of the metabolic indices, such as cholesterol, triglycerides, blood glucose, or insulin resistance, as seen with some of the other atypical antipsychotics. Ziprasidone has recently been FDA-approved as an adjunct to lithium or valproate in prophylactic treatment of adult bipolar disorder.

Activity Monitoring Discriminates Between BP Kids and ADHD Kids

At the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in October 2010, Gianni Faedda of the Lucio Bini Mood Disorders Center reported that monitoring of activity, sleep, and circadian-rhythm disturbances can be used to distinguish children with a diagnosis of bipolar illness (who showed more hyperactivity and less sleep), from children with ADHD and control children without illness.

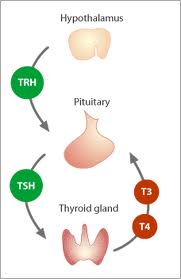

Thyroid Abnormalities Common in Childhood Mental Illness

At the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in October 2010, Maria Gariup of Barcelona, Spain reported that thyroid abnormalities are common among children with major psychiatric diagnoses and, in particular, high levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) are common among those with bipolar illness.

At the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in October 2010, Maria Gariup of Barcelona, Spain reported that thyroid abnormalities are common among children with major psychiatric diagnoses and, in particular, high levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) are common among those with bipolar illness.

Editor’s Note: These findings may relate to reports of a greater incidence of anti-thyroid antibodies in adult patients with bipolar disorder compared with many other psychiatric groups.

Stress or Ultrasonic Stimulation In Utero Could Alter Neuronal Migration Patterns

At the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in October 2010, Hanna Stevens of the Yale Child Study Center reported that rat pups in utero who experienced prenatal stress (i.e., when the pregnant rat was restrained during the last week of pregnancy) had fewer neurons containing GABA, which is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, than control pups. This deficit may reflect a delay in the neurons’ ventral to rostral migration or in their maturation. These deficits in GABAergic neurons following prenatal stress are noteworthy in light of the deficits in GABAergic neurons found in adults with bipolar illness. This research is unusual in that it suggests that prenatal stress can affect neuronal numbers.

Editor’s Note: Stevens was aware of data from the renowned neuroanatomist Pasco Rakic, also at Yale. Some years ago Rakic reported that ultrasonic stimulation of the brain had major disorganizing effects on neuronal migration in the primate brain. Since prenatal stress and ultrasonic stimulation can affect neuronal migration, and dysregulation of neuronal migration has been implicated in autism, these data raise the hypothesis (so far untested) that one possible reason for the recent increases in the incidence of autism is the increased use of sonograms to monitor various aspects of prenatal growth and development during pregnancy. These preclinical findings deserve to be further studied for their potential relevance to humans.