THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF SCHIZOPHRENIA IS BECOMING CLEARER

David Lewis of U. Pittsburgh showed that the glutamate neurons in the prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia are deficient in the gamma (30-50 Hz) oscillations that are responsible for normal working memory.

Not only are dendrites and spines deficient in these neurons in layer 3 of the cortex, but there is a deficit in parvalbumin GABA inhibitory neurons. The GABA enzyme GAD 67 is lower, producing less inhibition. The frontal neurons are hypoactive and there is less BDNF and oxidative phosphorylation present, yielding decreases in mitochondrial function.

Risk Gene for Bipolar Disorder Implicated in Depressed Behaviors and Abnormal Firing of GABA Neurons

At a 2018 scientific meeting and in a 2017 article in the journal PNAS, researcher Shanshan Zhu and colleagues reported that mice genetically engineered to lack the protein Ankyrin-G in certain neurons showed increases in depression- and mania-like behavior after being exposed to defeat stress (by repeatedly being placed in physical proximity to a larger, more aggressive mouse), which is often used to model human depression.

The researchers targeted the gene ANK3, which is responsible for the production of Ankyrin-G, and has been linked to bipolar disorder in genome-wide association studies. By manipulating the gene, they could eliminate Ankyrin-G in pyramidal neurons in the forebrain, a region relevant to many psychiatric disorders. Pyramidal neurons perform key brain functions, sending nerve pulses that lead to movement and cognition.

The missing Ankyrin-G affected sodium channels (which allow for the flow of sodium ions in and out of cells) and potassium channels. The neurochemical GABA (which typically inhibits nerve impulses) was also dysregulated, resulting in the kind of disinhibition seen in psychosis. Mice showed dramatic behavioral changes ranging from hyperactivity to depression-like behavior (e.g. giving up in a forced swimming test). The hyperactivity decreased when the mice were given treatments for human mania, lithium or valproic acid.

While mutations in the ANK3 gene may disturb sodium channels, another gene linked to depression and bipolar disorder, CACNA1C, affects calcium channels.

In a related study by researcher Rene Caballero-Florán and colleagues that was also presented at the meeting, mice were genetically engineered in such a way that interactions between Ankyrin-G and GABA Type A Receptor-Associated Protein (GABARAP) were disrupted, leading to deficits in inhibitory signaling. These deficits were partially corrected when the mice were treated with lithium.

The study by Caballero-Florán and colleagues used mice with a mutation known as W1989R in the ANK3 gene. Through a program that examines the genes of people with bipolar disorder, the researchers also identified a family with this genetic mutation, including a patient with type I bipolar disorder with recurrent mania and depression who has responded well to lithium treatment.

Scientific Mechanisms of Rapid-Acting Antidepressants

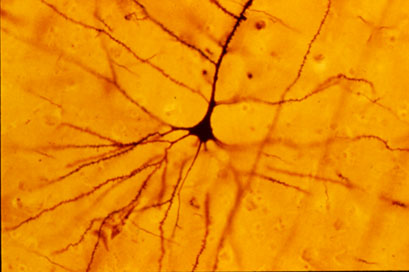

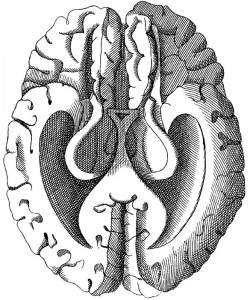

A pyramidal cell (Photo by Bob Jacobs, Laboratory of Quantitative Neuromorphology Department of Psychology Colorado College)

At a recent symposium, researcher Francis McMahon provided electrophysiological evidence that several different types of rapid-acting antidepressants—low-dose ketamine, scopolamine, and rapastinel (a partial agonist of the neurotransmitter NMDA)—act by decreasing the inhibitory effects of GABAergic interneurons on excitatory neurons called pyramidal cells, thus increasing synaptic firing.

Researcher Ronald Duman further dissected these effects, showing that ketamine and its active metabolite norketamine reduce the steady firing rate of GABA interneurons by blocking NMDA receptors, while the partial agonist rapastinel acts on the glutamate neurons directly, and both increase the effects of a type of glutamate receptors known as AMPA. These effects were demonstrated using a virus to selectively knock out GluN2B glutamate receptor subunits in either GABA interneurons or glutamate neurons.

Increasing AMPA activity increases synapse number and function and also increases network connectivity, which can reverse the effects of stress. Duman and colleagues further showed that when light is used to modulate pyramidal cells (a process called optogenetic stimulation) in the medial prefrontal cortex, different effects could be produced. Stimulating medial prefrontal cortex cells that contained dopamine D1 receptors, but not D2 receptors, produced rapid and sustained antidepressant effects. Conversely, inhibiting these neurons blocked the antidepressant effects of ketamine. Stimulating the terminals of these D1-containing neurons in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala was sufficient to reproduce the antidepressant effects. These data suggest that stimulation of glutamate D1 pyramidal neurons from the medial prefrontal cortex to the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala is both necessary and sufficient to produce the antidepressant effects seen with ketamine treatment.

Researcher Hailan Hu reported that NMDA glutamate receptors drive the burst firing of lateral habenula (LHb) neurons, which make up the depressogenic or “anti-reward center” of the brain and appear to mediate anhedonic behavior (loss of interest or enjoyment) in animal models of depression. Ketamine blocks the burst firing of the LHb neurons, which disinhibits monoamine reward centers, enabling ketamine’s rapid-onset antidepressant effects. This may occur because inhibitory metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR-2) are activated, decreasing the release of glutamate.

MGluR-2 may also help explain the antidepressant effects of acetyl-L-carnitine supplements. L-carnitine is an amino acid that is low in the blood of depressed patients. The supplement acetyl-L-carnitine (ACL) activates the DNA promoter for mGluR-2, increasing its production and thus decreasing excess glutamate release. The acetyl group of the ACL binds to the DNA promoter for mGluR-2, thus this process seems to be epigenetic. Epigenetic mechanisms affect the structure of DNA and can be passed on to offspring even though they are not encoded in the DNA’s genetic sequence.

Vitamin D3 Reduces Symptoms of Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

Vitamin D3 tends to be low in children and adolescents with mania, but supplements may help. In a small open study published in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology in 2015, Elif M. Sikoglu and colleagues administered 2000 IU of vitamin D3 per day to youth aged 6–17 for eight weeks. Sixteen of the participants had bipolar spectrum disorders (including subthreshold symptoms) and were exhibiting symptoms of mania. Nineteen participants were typically developing youth.

Vitamin D3 tends to be low in children and adolescents with mania, but supplements may help. In a small open study published in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology in 2015, Elif M. Sikoglu and colleagues administered 2000 IU of vitamin D3 per day to youth aged 6–17 for eight weeks. Sixteen of the participants had bipolar spectrum disorders (including subthreshold symptoms) and were exhibiting symptoms of mania. Nineteen participants were typically developing youth.

At the beginning of the study, the youth with bipolar spectrum disorders had lower levels of the neurotransmitter GABA in the anterior cingulate cortex than did the typically developing youth. Following the eight weeks of vitamin D3 supplementation, mania and depression symptoms both decreased in the youth with bipolar spectrum disorders, and GABA in the anterior cingulate cortex increased in these participants.

Editor’s Note: GABA dysfunction has been implicated in the manic phase of bipolar disorder. While larger controlled studies of vitamin D supplementation are needed, given the high incidence of vitamin D deficiency in youth in the US, testing and treating these deficiencies is important, especially among kids with symptoms of bipolar illness.

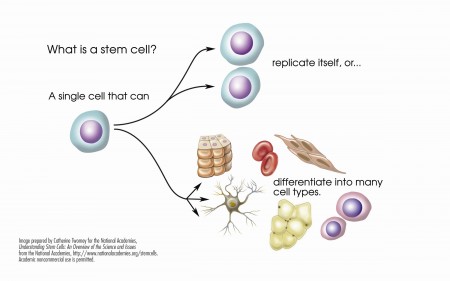

Stem Cell Research May Help Explain Biochemistry of Bipolar Disorder

At the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, researcher Martin McInnis described how stem cells can be used to identify biochemical abnormalities in patients with bipolar disorder. In this research, the stem cells, or IPSCs (for induced pluripotential stem cells), are created when cells from skin fibroblasts, which produce connective tissue, are treated with chemicals that cause them to de-differentiate back into stem cells.

McInnis identified several abnormalities in the stem cells of patients with bipolar disorder. Stem cells with the gene CACNA1C, which is associated with vulnerability to bipolar disorder, fired more rapidly than non-CACNA1C stem cells. There were other abnormalities at the NMDA glutamate receptor and an imbalance of the neurotransmitter GABA in the cells. When the cells were treated with lithium, some of these abnormalities were reversed. In the cells with the CACNA1C gene, lithium normalized the firing rate. Lithium aslo re-balanced the distribution of GABA in the cells.

McInnis hopes that this stem cell research will shed light on the abnormalities associated with bipolar disorder, help explain how lithium corrects some of these, and lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches.

Thalamus Implicated in Depression-Like Behavior and Resilience to It

At the 2014 meeting of the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology, researcher Scott Russo described characteristics of rodents who showed depression-like behavior after 10 days of exposure to a larger, more aggressive animal (a phenomenon known as defeat stress). These animals exhibited many behaviors that resembled human depression, including anxiety-like behaviors while navigating a maze; activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; circadian rhythm abnormalities; metabolic changes such as glucose intolerance; susceptibility to addiction; anhedonia, a lack of interest in sucrose, sex or intracranial self-stimulation; and profound and permanent social avoidance.

In susceptible animals, Russo found anatomical changes in the GABAergic neurons of the nucleus accumbens (also known as the ventral striatum), including increased numbers of synapses and a greater number of stubby spines on dendrites (the branched projections of neurons where electrical signals are passed from one cell to the next), as well as greater excitability of glutamatergic input, observed as excitatory post-synaptic potentials.

Russo’s attempt to identify these key neurons among the billions of neurons and the 100 to 500 trillion synapses in the brain was like the search for a needle in a haystack, but thinks he found it. The medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens contain GABA and receive synapses from the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and intralaminar nucleus of the thalamus (ILT), in addition to dopamine inputs from the VTA, and cholinergic, somatostatin, and orexin inputs. Russo found that it was the ILT inputs that conveyed susceptibility to defeat stress, and their presynaptic endings showed increased levels of glutamate transporters (VGLUT-2). Driving the ILT was sufficient to cause the rodents to display the depression-like behaviors, and silencing the ILT during defeat stress prevented the susceptible behaviors (like social avoidance) and promoted resilience.

Neurosteroid Allopregnanolone May Improve Bipolar Depression

Sherman Brown of the University of Texas Southwestern reports that the neurosteroid allopregnanolone has positive effects in bipolar depression. Patients in Brown’s study received doses of 100mg capsules twice daily during the first week, then one capsule in the morning and two capsules in the evening during the second week, and two capsules in the morning and three capsules in the evening during the third week.

Neurosteroids can change the excitability of neurons through their interactions with the neurotransmitters that carry signals from neurons across synapses. Among the various types of neurotransmitters, GABA plays an inhibitory role, while glutamate is responsible for excitability. Allopregnanolone, which is naturally produced in the body, has positive effects on GABA receptors and inhibitory effects on glutamate NMDA receptors, so that it increases the balance of inhibition (GABA) over excitation (glutamate).

Vitamin D3 Is Low In Children And Adolescents With Mania, But Supplements Help

Vitamin D3 is low in children and adolescents with mania, but taking a supplement could help. Vitamin D3, which we absorb via food and sunlight, is converted by the liver to a form called 25-OH-D. In a small study, Elif Sikoglu et al. found that children and teens with mania had lower levels of 25-OH-D in their blood compared to typically developing youth of similar ages. This deficit was associated with lower brain GABA levels measured with magnetic resonance spectroscopy. GABA dysfunction has been implicated in the manic phase of bipolar disorder. An 8-week trial of Vitamin D3 supplements significantly reduced manic symptoms and tended to increase GABA levels.

Editor’s Note: Other data have suggested that children with psychosis have low Vitamin D3, and in a recent clinical trial in adults, Vitamin D3 supplementation improved antidepressant response more than placebo. Many children in the US are Vitamin D deficient. Test them and, if necessary, treat them, especially if they have bipolar disorder.

Neurological Biomarkers May Eventually Predict Response to Antidepressants

T.L. Lauriat reported at the 51st Annual Meeting of the National Institute of Mental Health’s New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (NCDEU) in 2011 that low baseline levels of the neurotransmitter GABA in the brains of depressed patients were associated with greater response to antidepressants. GABA was measured using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).

T.L. Lauriat reported at the 51st Annual Meeting of the National Institute of Mental Health’s New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (NCDEU) in 2011 that low baseline levels of the neurotransmitter GABA in the brains of depressed patients were associated with greater response to antidepressants. GABA was measured using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).

These data raise the possibility that easily observed neurobiological markers, such as levels of GABA or the neurotransmitter glutamate, may ultimately be helpful in predicting clinical response to particular treatments.

Clinical Evidence May Explain the Mechanisms of Ketamine’s Rapid Acting Antidepressant Effects

At the 51st Annual Meeting of the National Institute of Mental Health’s New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (NCDEU) in 2011, C.G. Abdallah from SUNY Downstate Medical Center reported on a study of intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Twelve medication-free participants aged 18-65 received 0.5mg/kg ketamine over 40 minutes. There was a rapid-onset antidepressant effect, as there has been in other studies of unipolar and bipolar depressed patients. In a subgroup of 4 patients examined with magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), there were rapid increases in brain GABA followed shortly thereafter by increases in brain glutamate concentrations.

Editor’s note: The rapid increases in GABA and glutamate that occur after the administration of intravenous ketamine may help account for its therapeutic effects. Other studies have shown that brain GABA is low in depressed patients, so the rapid increase in GABA with ketamine administration could partly explain the antidepressant effects of the drug. The role of the glutamate increases remains to be further explored.

Neli and associates from Yale had reported that in animals, ketamine was able to rapidly alter synapse structure and function. In an animal model of depression, rodents are exposed to chronic and unpredictable stress and develop depressive-like behavior. The mature, mushroom-shaped spines on their dendrites (the parts of neurons that receive synapses and determine the neuron’s excitability) also lose their shape, becoming straighter and spikier like immature spines. Intravenous ketamine not only improves the animals’ behavior, but also increases the number of mushroom-shaped spines within a matter of hours, rapidly improving synaptic function. This effect of ketamine was dependent on a novel intracellular pathway involving the enzyme mTOR, which if blocked prevented the re-emergence of the mature spines.

In the brains of depressed humans studied at autopsy there is reduced neural volume in the frontal cortex, which could possibly be related to dendritic atrophy and associated changes in spine shape as it appears to be in rodents. The animal data suggest the remarkable possibility that intravenous ketamine’s rapid onset of antidepressant effects could also be associated with rapid improvement in the microanatomy of the brain.

The data on ketamine’s effects in animals and the new clinical data showing that GABA and glutamate increases occurred rapidly in depressed patients administered ketamine provide further insight into the potential mechanisms of ketamine’s effect.