Sleep Disturbances in Pediatric Bipolar NOS is the Same as in BP I

Gianni Faedda reported in Frontiers in Psychiatry (2012) that decreased need for sleep is as prominent in BP NOS children as in those with BP I. So it appears that with the exception of only brief periods of mania in BP NOS, these children have similar characteristics to those with full blown BP I. Thus in addition to the briefer periods of mania, one should be on the look out for all the symptoms of bipolar disorder that are not typical of ADHD, including brief or extended periods of euphoria, decreased need for sleep, more extreme degrees of irritability and poor frustration tolerance, hallucination, delusions, suicidal and homicidal ideation, more severe depression, and increases in sexual interest and actions. When these are present, the bipolar mood instability should be treated first and only then small doses of psychomotor stimulants can be used to treat what ever residual ADHD remains. The typical symptoms of ADHD are very of present and comorbid in childhood onset bipolar disorder and cannot be used to discriminate the two diagnoses. The children with BP NOS are as dysfunctional as those with BP I and take longer to stabilize, so pharmacological treatment may need to be intensive, multimodal, and supplemented by Family Focused Therapy (FFT) or a related family therapy. It is most often not conceptualized as such, but BP NOS as well as BP I should be considered as a medical emergency and handled by a sophisticated pediatrician and/or referred for psychiatric consultation and therapy. The longer bipolar disorder is not treated, the worse the outcome is in adulthood.

Lumateperone Improves Bipolar Depression Symptoms

At a recent scientific meeting, Suresh Durgam of Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc. reported on a study of lumateperone tosylate for the treatment of bipolar depression. Lumateperone tosylate is a mechanistically novel antipsychotic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of schizophrenia.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the drug showed efficacy in bipolar I and II depression. In a 6-week study, 377 patients received either 42 mg/day of lumateperone or placebo, and 333 (87.4%) completed treatment. Lumateperone treatment significantly improved total scores on the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) compared with placebo. Item analysis revealed that 8 of 10 MADRS items improved significantly in comparison with placebo by day 29, and all items did by day 43. The largest effects were in reported sadness, apparent sadness, inner tension and reduced sleep. Durgam and colleagues concluded that lumateperone at a dose of 42mg improves a broad range of symptoms in bipolar I and bipolar II depression.

Prazosin Effective and Well-Tolerated for PTSD in Young People

In a poster session at the 2019 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), three posters highlighted the efficacy and tolerability of prazosin, a drug typically used to treat high blood pressure, for the treatment of childhood-onset post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Researchers Samira Khan and Taniya Pradhan of West Virginia University reviewed cases in which 39 patients aged 8–19 received 1–5 mg of prazosin at bedtime. The mean dose was 1.72 mg. Sleep (including nightmares) improved in 92.3% of the youths, and mood improved in 33.3%. Sleep improved more in patients who received lower doses (1–2 mg) than those who received higher doses. About 70% of the patients whose data were included in the case series were also receiving psychotherapy while being treated with prazosin.

In another poster, researcher Vladimir Ferrafiat and colleagues from University Hospital of Rouen in France reported on a prospective study of 18 participants under age 15 with severe PTSD who were unresponsive to other medications. The participants were given 1 mg of prazosin at bedtime, which was increased to 3 mg in 20% of the participants. The youth were assessed weekly over a one-month period. Improvement was seen in all domains, including sleep, nightmares and daytime intrusive symptoms. Prazosin was well tolerated, with only one patient experiencing low blood pressure, which did not necessitate withdrawal from the study.

In the final poster, researcher Fatima Motiwala and colleagues reviewed the literature on the treatment of PTSD in children. Motiwala indicated that among the options, prazosin was widely used in her hospital, at doses starting at 1 mg given at bedtime and increasing to a mean of 4 mg at bedtime with excellent results and tolerability.

Editor’s Note: Although these were not double-blind controlled studies, the findings are noteworthy in that they provide consistent data on the effectiveness and tolerability of prazosin in low doses in children with PTSD, essentially mirroring controlled data in adults, where higher doses are typically required.

Using Light to Improve Sleep and Depression

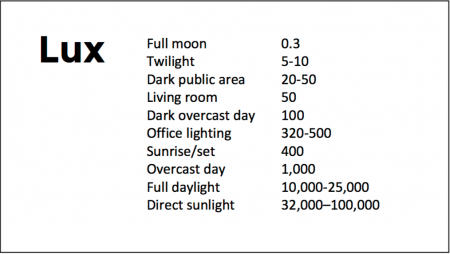

At the 2018 meeting of the North Carolina Psychiatric Association, researcher Chris Aiken described the phenomenon of sleep inertia, when people are awakened from deep sleep by an alarm, rather than waking at the end of a sleep cycle, and are groggy for 15 minutes. Depressed people may stay groggy for 4 hours. A dawn simulator may help. These lights turn on gradually over the course of 30 to 60 minutes, reaching 250 lux while the patient is still asleep. Dawn simulators have worked in eight out of ten controlled clinical trials to help people with seasonal affective disorder, adolescents, and normal adults wake up more easily. They range in cost from $25 to $90 and some brands include PER2LED or LightenUp. Aiken says dawn simulators can improve depression, sleep quality, and cognition.

Evening and nighttime light: Bright lights and blue light, like the light that comes from electronic screens, can shut down the body’s secretion of melatonin, making people awake and alert in the evening when they should be getting sleepy. Dim light or glasses that filter out blue light allow increases in melatonin secretion in the evening, while bright light suppresses it. Missing this early melatonin pulse creates “night owls” who have delayed sleep onset.

Because light still reaches our eyes through our eyelids as we sleep, even low-level light during the night impairs sleep, cognition, and learning, and increases the risk of depression by a hazard ratio of 1.8 (about double the risk). A 2017 study by Kenji Obayashi in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that bedroom light above 5 lux elevated rates of depression in older adults after two years of followup. Living room light averaged around 50 lux and increased depression further.

The treatment is turning off TVs, electronic screens, and cellphones in the evening or wearing blue-blocking glasses, which can be found for less than $10. Blue-blocking glasses can increase calmness and reduce anxiety, and even are effective in treating mania. Then, during sleep, wear an eye mask or get light-blocking blinds or curtains for windows. For a complete blackout, use blackout curtains, aluminum foil over windows, electric tape over LED lights, or try sleeping in the basement.

Aiken suggests that to re-instate healthy sleep patterns, people should institute virtual darkness from 6pm to 8am, including wearing blue-blocking glasses when out of bed. Then they should institute total darkness or wear an eye mask when in bed. When symptoms improve, this routine can gradually be shifted to begin later in the evening, such as two hours before bedtime.

Blue light filters are also available for smartphones and tablets including Apple Nightshift mode, Kindle BlueShade, and Android Twilight and Blue Light Filter.

Glasses that filter out blue light include Uvex Ultraspec 2000, 50360X ($7 on Amazon) and Uvex Skyper 351933X ($7-10 on Amazon). The website lowbluelights.com sells blue-blocking glasses from $45 and a variety of other blue-free lighting products such as lightbulbs and flashlights.

Bright light therapy for unipolar and bipolar depression: 30 minutes of bright light (7,500 to 10,000 lux) in the morning can help treat depression in unipolar and bipolar disorder and seasonal affective disorder. The effects usually take 3 to 7 days to set in, but they only last while a patient continues using the bright light in the morning. Researcher Dorothy K. Sit and colleagues found that bright light therapy in the morning sometimes caused hypomanic reactions in people with bipolar disorder, and reported in a 2018 article in the American Journal of Psychiatry that midday light therapy (from noon to 2:30pm) was also effective without this unwanted effect. However, a 2018 article by Ne?e Yorguner Küpeli and colleagues in the journal Psychiatry Research suggested that a half hour of morning light for two weeks was sufficient to bring about improvement in 81% of patients with bipolar disorder and did not cause serious side effects.

Melatonin regimen for sleep onset delay: Melatonin can be used to treat severe night-owls with a very late onset of sleep (for example, going to bed at 2 or 3am and sleeping late into the morning). Melatonin can help with sleep onset to some extent when used at bedtime, but in those with an extreme phase shift, researcher Alfred J. Lewy recommends a regimen of low dose priming with 400–500 micrograms of melatonin at 4pm and then a full dose of 3 milligrams of melatonin at midnight. The 4pm priming dose helps pull back the delayed onset of the body’s secretion of melatonin toward a more normal schedule.

Clinical Vignettes from Dr. Elizabeth Stuller

Dr. Elizabeth Stuller, a staff psychiatrist at the Amen clinics in Washington, DC and CEO of private practice Stuller Resettings in Baltimore, MD, provided this editor (Robert M. Post) with several interesting anecdotal observations based on her wide clinical experience with difficult-to-treat mood disordered patients.

Dr. Elizabeth Stuller, a staff psychiatrist at the Amen clinics in Washington, DC and CEO of private practice Stuller Resettings in Baltimore, MD, provided this editor (Robert M. Post) with several interesting anecdotal observations based on her wide clinical experience with difficult-to-treat mood disordered patients.

- Stuller has used low-dose asenapine (Saphris), e.g. half a pill placed under the tongue, for depressed patients with alcohol use problems who have trouble getting to sleep. She has also used asenapine for rapid calming of agitated patients in her office.

- Stuller has also had success with the use of the atypical antipsychotic drug brexpiprazole (Rexulti) for patients with bipolar depression and low energy. She typically uses 0.5 mg/day for women and 1 mg/day for men. Stuller finds that there is little weight gain or akathisia with brexpiprazole.

- She has had success with the drug Nuedexta, which is a combination of dextromethorphan and quinidine and is approved for the treatment of sudden uncontrollable bouts of laughing or crying, known as pseudobulbar affect, which can occur as a result of neurological conditions or brain injuries. It is a combination of an NMDA antagonist and a sigma receptor agonist. Stuller starts with the 20mg dextromethorphan/10 mg quinidine dose once a day and increases to twice a day in week two. She finds it useful for behavioral effects of traumatic brain injury (TBI), anxiety resulting from the use of synthetic marijuana (sometimes called spice), and psychosis not otherwise specified. Stuller also finds that some patients appear to respond well to Nuedextra but not minocycline, or vice versa.

Editor’s Note: Note that these are preliminary clinical anecdotes conveyed in a personal communication, and have not been studied in clinical trials, thus should not be relied upon in the making of medical decisions. All decisions about treatment are the responsibility of a treating physician.

TDCS Can Change Sleep Duration

A German study published in 2016 suggests that transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) can affect the duration of a person’s nightly sleep. Lukas Frase and colleagues compared the effects of two different tDCS parameters and a sham stimulation on the sleep patterns of 19 healthy volunteers.

TDCS is a treatment in which an anode and a cathode electrode placed on the skull are used to apply a steady, low-level current of electricity to the brain.

Bi-frontal anodal stimulation, intended to increase arousal, significantly decreased total sleep time compared to the other two interventions.

Bi-frontal cathodal stimulation, intended to decrease arousal, did not increase total sleep time, possibly because there is a ‘ceiling’ beyond which good sleepers do not sleep longer.

EEG analysis showed that the anodal stimulation did increase arousal, while cathodal stimulation decreased it.

The research increases what is currently known about sleep-wake regulation by showing that total sleep time can be decreased using anodal tDCS. The researchers hope this knowledge can contribute to future treatments for disturbed arousal and sleep.

Ketamine Improves Sleep and Reduces Suicidal Thoughts in Certain Patients

Intravenous ketamine is known for its fast-acting antidepressant effects, which can appear within two hours of an infusion. Researchers are now investigating its use for the reduction of suicidal thoughts. In a study presented in a poster at the 2015 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, Jennifer L. Vande Voort and colleagues compared the sleep of patients whose suicidal thoughts decreased after a single ketamine infusion (0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes) to those whose suicidal thoughts remained.

Study participants whose suicidal thoughts diminished after one infusion of ketamine had better sleep quality the following night, with fewer disruptions in sleep than among those who did not have an anti-suicidal response to ketamine. The participants who responded well to ketamine had sleep quality similar to that of healthy controls.

Vande Voort and colleagues hope that these new findings about ketamine’s effect on sleep may provide clues to the biological mechanism behind ketamine’s effect on suicidal ideation.

Depression in Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

The incidence of irritable bowel disease has been increasing in recent years as obesity has increased. At a symposium at the 2014 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, researcher Eva Szigethy discussed depression in inflammatory bowel disease, which most often involves Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. These conditions are associated with increased levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin 1 (IL-1), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and TNF alpha, and these in turn induce the acute phase reactive protein called c-reactive protein (CRP). The interleukins peak in the first 12 hours after an inflammatory challenge and CRP peaks at 48 hours and returns to normal at 120 hours. Il-6 is most closely associated with the somatic symptoms of inflammation, including depression, fatigue, loss of appetite, and decreased sleep, while TNF alpha is associated with non-somatic symptoms, such as irritability.

The incidence of irritable bowel disease has been increasing in recent years as obesity has increased. At a symposium at the 2014 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, researcher Eva Szigethy discussed depression in inflammatory bowel disease, which most often involves Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. These conditions are associated with increased levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin 1 (IL-1), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and TNF alpha, and these in turn induce the acute phase reactive protein called c-reactive protein (CRP). The interleukins peak in the first 12 hours after an inflammatory challenge and CRP peaks at 48 hours and returns to normal at 120 hours. Il-6 is most closely associated with the somatic symptoms of inflammation, including depression, fatigue, loss of appetite, and decreased sleep, while TNF alpha is associated with non-somatic symptoms, such as irritability.

Szigethy found that in a randomized trial of cognitive behavior therapy versus supportive therapy in children with inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory activity decreased significantly with cognitive behavioral therapy, and the therapy particularly helped the somatic symptoms of fatigue, sleep disorder, anhedonia (loss of interest in activities once enjoyed), appetite suppression, and mood dysregulation. In contrast, when antidepressants are given to those with inflammatory bowel disease, the drugs are not particularly helpful for these somatic symptoms. Inflammatory bowel diseases are treated with steroids in 21% of patients and with a genetically engineered drug called infliximab in 30%. Adding cognitive behavioral therapy to the regimen decreases CRP and red cell sedimentation rate, an associated measure of inflammation.

The discussant of the symposium on inflammation, Frank Lotrich, described how inflammation alters sleep, and this appeared to interact with genetic risk of illness. For example, those with certain genetic variations (the short SS allele of the serotonin transporter and the val-66-met allele of proBDNF) were most likely to experience sleep disturbance following treatment with interferon gamma, a treatment that fights the virus that causes Hepatitis C, creating inflammation in the process. Interferon gamma causes depression in about one-third of the patients who take it.

Lotrich pointed out that low levels of omega-3 fatty acids are associated with increased irritability and anger, and this is related to the presence of the A allele of TNF alpha. TNF alpha is also closely linked with irritability and anger, suggesting the possible benefits of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation to target irritability and anger more selectively. This would be consistent with the data of researcher Mary A. Fristad.

Il-6 is closely associated with the somatic symptoms of depression, particularly poor sleep, which is itself associated with increases in depression. This is consistent with inflammation being a marker of poor response to antidepressants; Lotrich noted that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which help depression, are far more effective against the non-somatic aspects of depression and less effective against low energy, decreased interest, and fatigue. However, extrapolating from the data on inflammatory bowel disease, cognitive behavioral therapy may be most helpful on these somatic symptoms.

Clarifying the role of melatonin receptors in sleep

The antidepressant agomelatine (which is available in many countries, but not the US) and the anti-insomnia drug ramelteon (Rozerem) both act as agonists at melatonin M1 and M2 receptors. New research is clarifying the role of these receptors in sleep.

In new research from Stefano Comai et al., mice who were genetically altered to have no M1 receptor (MT1KO knockout mice) showed a decrease in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is linked to dreaming, and an increase in slow wave sleep. Mice who were missing the M2 receptor (MT2KO knockout mice) showed a decrease in slow wave sleep. The effects of knocking out a particular gene like M1 or M2 end up being opposite to the effect of stimulating the corresponding receptor.

The researchers concluded that MT1 receptors are responsible for REM sleep (increasing it while decreasing slow wave sleep), and MT2 receptors are responsible for slow wave non-REM sleep.

The new information about these melatonin receptors may explain why oral melatonin supplements can make a patient fall asleep faster, but do not affect the duration of non-REM sleep. The authors suggest that targeting MT2 receptors could lead to longer sleep by increasing slow wave sleep, potentially helping patients with insomnia.

Depression in Youth Is Tough to Treat and Requires Persistence and Creativity

At a symposium on ketamine for the treatment of depression in children at the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, David Brent, a professor at the University of Pittsburg, gave the opening talk on the fact that as many as 20% of adolescents who are depressed fail to improve, develop chronic illness, and are thus in need of alternatives to traditional treatment. Predictors of non-improvement include substance use, low-level manic symptoms, poor adherence to a medication regimen, low blood levels of antidepressants, family conflict, high levels of inflammation in the body, and importantly, maternal depression. In adolescents insomnia was associated with poor response, but in younger children insomnia was associated with a better response.

At a symposium on ketamine for the treatment of depression in children at the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, David Brent, a professor at the University of Pittsburg, gave the opening talk on the fact that as many as 20% of adolescents who are depressed fail to improve, develop chronic illness, and are thus in need of alternatives to traditional treatment. Predictors of non-improvement include substance use, low-level manic symptoms, poor adherence to a medication regimen, low blood levels of antidepressants, family conflict, high levels of inflammation in the body, and importantly, maternal depression. In adolescents insomnia was associated with poor response, but in younger children insomnia was associated with a better response.

Brent suggested using melatonin and sleep-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in youth, but not using trazodone (which is commonly prescribed). Trazodone is converted to a compound called Meta-chlorophenylpiperazine or MCPP, which induces anxiety and dysphoria. MCPP is metabolized by hepatic enzymes 2D6, and fluoxetine and paroxetine inhibit 2D6, so if trazodone is combined with these antidepressants, the patient may get too much MCPP.

Surprisingly and contrary to some data in adults about the positive effects of therapy in those with abuse histories, in the study TORDIA (Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents), if youth with depression had experienced abuse in childhood, they did less well on the combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared to SSRIs alone.