Using Light to Improve Sleep and Depression

At the 2018 meeting of the North Carolina Psychiatric Association, researcher Chris Aiken described the phenomenon of sleep inertia, when people are awakened from deep sleep by an alarm, rather than waking at the end of a sleep cycle, and are groggy for 15 minutes. Depressed people may stay groggy for 4 hours. A dawn simulator may help. These lights turn on gradually over the course of 30 to 60 minutes, reaching 250 lux while the patient is still asleep. Dawn simulators have worked in eight out of ten controlled clinical trials to help people with seasonal affective disorder, adolescents, and normal adults wake up more easily. They range in cost from $25 to $90 and some brands include PER2LED or LightenUp. Aiken says dawn simulators can improve depression, sleep quality, and cognition.

Evening and nighttime light: Bright lights and blue light, like the light that comes from electronic screens, can shut down the body’s secretion of melatonin, making people awake and alert in the evening when they should be getting sleepy. Dim light or glasses that filter out blue light allow increases in melatonin secretion in the evening, while bright light suppresses it. Missing this early melatonin pulse creates “night owls” who have delayed sleep onset.

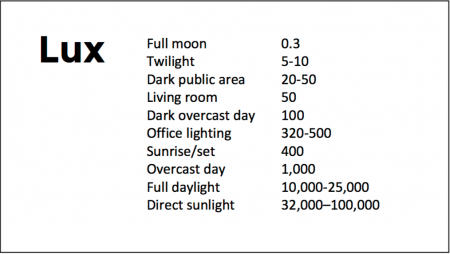

Because light still reaches our eyes through our eyelids as we sleep, even low-level light during the night impairs sleep, cognition, and learning, and increases the risk of depression by a hazard ratio of 1.8 (about double the risk). A 2017 study by Kenji Obayashi in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that bedroom light above 5 lux elevated rates of depression in older adults after two years of followup. Living room light averaged around 50 lux and increased depression further.

The treatment is turning off TVs, electronic screens, and cellphones in the evening or wearing blue-blocking glasses, which can be found for less than $10. Blue-blocking glasses can increase calmness and reduce anxiety, and even are effective in treating mania. Then, during sleep, wear an eye mask or get light-blocking blinds or curtains for windows. For a complete blackout, use blackout curtains, aluminum foil over windows, electric tape over LED lights, or try sleeping in the basement.

Aiken suggests that to re-instate healthy sleep patterns, people should institute virtual darkness from 6pm to 8am, including wearing blue-blocking glasses when out of bed. Then they should institute total darkness or wear an eye mask when in bed. When symptoms improve, this routine can gradually be shifted to begin later in the evening, such as two hours before bedtime.

Blue light filters are also available for smartphones and tablets including Apple Nightshift mode, Kindle BlueShade, and Android Twilight and Blue Light Filter.

Glasses that filter out blue light include Uvex Ultraspec 2000, 50360X ($7 on Amazon) and Uvex Skyper 351933X ($7-10 on Amazon). The website lowbluelights.com sells blue-blocking glasses from $45 and a variety of other blue-free lighting products such as lightbulbs and flashlights.

Bright light therapy for unipolar and bipolar depression: 30 minutes of bright light (7,500 to 10,000 lux) in the morning can help treat depression in unipolar and bipolar disorder and seasonal affective disorder. The effects usually take 3 to 7 days to set in, but they only last while a patient continues using the bright light in the morning. Researcher Dorothy K. Sit and colleagues found that bright light therapy in the morning sometimes caused hypomanic reactions in people with bipolar disorder, and reported in a 2018 article in the American Journal of Psychiatry that midday light therapy (from noon to 2:30pm) was also effective without this unwanted effect. However, a 2018 article by Ne?e Yorguner Küpeli and colleagues in the journal Psychiatry Research suggested that a half hour of morning light for two weeks was sufficient to bring about improvement in 81% of patients with bipolar disorder and did not cause serious side effects.

Melatonin regimen for sleep onset delay: Melatonin can be used to treat severe night-owls with a very late onset of sleep (for example, going to bed at 2 or 3am and sleeping late into the morning). Melatonin can help with sleep onset to some extent when used at bedtime, but in those with an extreme phase shift, researcher Alfred J. Lewy recommends a regimen of low dose priming with 400–500 micrograms of melatonin at 4pm and then a full dose of 3 milligrams of melatonin at midnight. The 4pm priming dose helps pull back the delayed onset of the body’s secretion of melatonin toward a more normal schedule.

Melatonin May Improve Headaches

A 2016 article in the Journal of Head and Face Pain reviewed randomized placebo-controlled trials of melatonin for the treatment of headaches. Author Amy A. Gelfand and colleagues reported that 10 mg of melatonin was superior to placebo in the treatment of cluster headaches. For treatment of migraines, 3 mg of immediate-release melatonin improved headaches compared to placebo, while 2 mg of sustained-release melatonin was insufficient.

The authors also found non–placebo controlled data suggesting that melatonin may be helpful for other types of headaches. More research is needed to clarify melatonin’s effects in different headache disorders.

Clarifying the role of melatonin receptors in sleep

The antidepressant agomelatine (which is available in many countries, but not the US) and the anti-insomnia drug ramelteon (Rozerem) both act as agonists at melatonin M1 and M2 receptors. New research is clarifying the role of these receptors in sleep.

In new research from Stefano Comai et al., mice who were genetically altered to have no M1 receptor (MT1KO knockout mice) showed a decrease in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is linked to dreaming, and an increase in slow wave sleep. Mice who were missing the M2 receptor (MT2KO knockout mice) showed a decrease in slow wave sleep. The effects of knocking out a particular gene like M1 or M2 end up being opposite to the effect of stimulating the corresponding receptor.

The researchers concluded that MT1 receptors are responsible for REM sleep (increasing it while decreasing slow wave sleep), and MT2 receptors are responsible for slow wave non-REM sleep.

The new information about these melatonin receptors may explain why oral melatonin supplements can make a patient fall asleep faster, but do not affect the duration of non-REM sleep. The authors suggest that targeting MT2 receptors could lead to longer sleep by increasing slow wave sleep, potentially helping patients with insomnia.

Buspirone and Melatonin Together May Treat Unipolar Depression

The combination of the anti-anxiety drug buspirone (trade name Buspar) and melatonin, a hormone that regulates cycles of sleep and waking, may be effective for depression. Researcher Maurizio Fava and other researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital report that low-dose buspirone (e.g. 15 mg/day) combined with a 3 mg dose of melatonin produced significant antidepressant effects in a six-week study of patients with unipolar depression.

While buspirone is not a potent antidepressant at low doses, the combination of buspirone and melatonin exerted significant effects, leading to better antidepressant response than did either placebo or 15 mg of buspirone alone. Another benefit of the combination is that the low dose of buspirone minimizes side effects.

Buspirone is a serotonin 5HT1A receptor partial agonist, meaning that it produces weak activity at this serotonin receptor, but does not allow it to get overstimulated.

Depression in Youth Is Tough to Treat and Requires Persistence and Creativity

At a symposium on ketamine for the treatment of depression in children at the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, David Brent, a professor at the University of Pittsburg, gave the opening talk on the fact that as many as 20% of adolescents who are depressed fail to improve, develop chronic illness, and are thus in need of alternatives to traditional treatment. Predictors of non-improvement include substance use, low-level manic symptoms, poor adherence to a medication regimen, low blood levels of antidepressants, family conflict, high levels of inflammation in the body, and importantly, maternal depression. In adolescents insomnia was associated with poor response, but in younger children insomnia was associated with a better response.

At a symposium on ketamine for the treatment of depression in children at the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, David Brent, a professor at the University of Pittsburg, gave the opening talk on the fact that as many as 20% of adolescents who are depressed fail to improve, develop chronic illness, and are thus in need of alternatives to traditional treatment. Predictors of non-improvement include substance use, low-level manic symptoms, poor adherence to a medication regimen, low blood levels of antidepressants, family conflict, high levels of inflammation in the body, and importantly, maternal depression. In adolescents insomnia was associated with poor response, but in younger children insomnia was associated with a better response.

Brent suggested using melatonin and sleep-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in youth, but not using trazodone (which is commonly prescribed). Trazodone is converted to a compound called Meta-chlorophenylpiperazine or MCPP, which induces anxiety and dysphoria. MCPP is metabolized by hepatic enzymes 2D6, and fluoxetine and paroxetine inhibit 2D6, so if trazodone is combined with these antidepressants, the patient may get too much MCPP.

Surprisingly and contrary to some data in adults about the positive effects of therapy in those with abuse histories, in the study TORDIA (Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents), if youth with depression had experienced abuse in childhood, they did less well on the combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared to SSRIs alone.