Transcranial Near-Infrared Light May Treat Brain Injury and Neurodegeneration

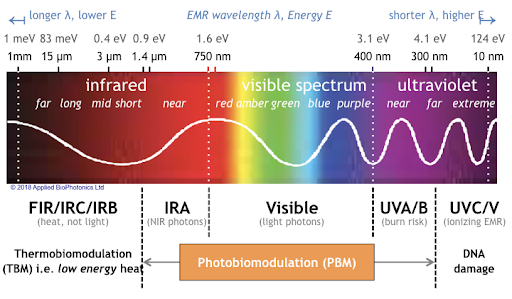

At the 2021 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, there was a symposium on treatment with near-infrared light chaired by researchers Paolo Cassano and Dan Iosifescu. The treatment is known as transcranial photobiomodulation (PBM) with near-infrared light. A device worn on the head delivers infrared light that penetrates the cerebral cortex and can modulate cortical excitability. It has a variety of effects including promoting neuroplasticity, improving oxygenation, and decreasing inflammation and oxidative stress.

A number of studies exploring the possibility that PBM could be used as a clinical treatment for conditions such as depression, brain injury, or dementia were presented at the symposium.

Researcher Lorelei Tucker discussed promising findings from an animal model in which rats with stroke or brain injuries showed improvement after being treated with PBM.

Cassano discussed studies aimed at refining which brain areas should be targeted with PBM and how much light should be delivered in order to improve depression. In double-blind, sham-controlled studies in people with major depression, targeting the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex with PBM improved their symptoms.

Researcher Benjamin Vakoc discussed a study of low-level light therapy (LLLT) using near-infrared light compared to a sham procedure in 68 people with moderate traumatic brain injury. The researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess changes in white matter in the brain over time in people recovering from an acute brain injury. Patterns of changes in white matter were different for those who received LLLT compared to those who received the sham procedure.

Researcher Linda Chao described a very small study to determine whether PBM could improve symptoms of dementia. Four patients received typical dementia care while four others underwent home treatments with the commercially available Vielight Neuro Gamma device, which delivers PBM via both the scalp and an insert in the nose. After 12 weeks, the PBM group showed improvements in cognition and brain connectivity.

Editor’s Note: We will be watching the literature to follow advances in this promising novel method of neuromodulation.

Clinical Vignettes from Dr. Elizabeth Stuller

Dr. Elizabeth Stuller, a staff psychiatrist at the Amen clinics in Washington, DC and CEO of private practice Stuller Resettings in Baltimore, MD, provided this editor (Robert M. Post) with several interesting anecdotal observations based on her wide clinical experience with difficult-to-treat mood disordered patients.

Dr. Elizabeth Stuller, a staff psychiatrist at the Amen clinics in Washington, DC and CEO of private practice Stuller Resettings in Baltimore, MD, provided this editor (Robert M. Post) with several interesting anecdotal observations based on her wide clinical experience with difficult-to-treat mood disordered patients.

- Stuller has used low-dose asenapine (Saphris), e.g. half a pill placed under the tongue, for depressed patients with alcohol use problems who have trouble getting to sleep. She has also used asenapine for rapid calming of agitated patients in her office.

- Stuller has also had success with the use of the atypical antipsychotic drug brexpiprazole (Rexulti) for patients with bipolar depression and low energy. She typically uses 0.5 mg/day for women and 1 mg/day for men. Stuller finds that there is little weight gain or akathisia with brexpiprazole.

- She has had success with the drug Nuedexta, which is a combination of dextromethorphan and quinidine and is approved for the treatment of sudden uncontrollable bouts of laughing or crying, known as pseudobulbar affect, which can occur as a result of neurological conditions or brain injuries. It is a combination of an NMDA antagonist and a sigma receptor agonist. Stuller starts with the 20mg dextromethorphan/10 mg quinidine dose once a day and increases to twice a day in week two. She finds it useful for behavioral effects of traumatic brain injury (TBI), anxiety resulting from the use of synthetic marijuana (sometimes called spice), and psychosis not otherwise specified. Stuller also finds that some patients appear to respond well to Nuedextra but not minocycline, or vice versa.

Editor’s Note: Note that these are preliminary clinical anecdotes conveyed in a personal communication, and have not been studied in clinical trials, thus should not be relied upon in the making of medical decisions. All decisions about treatment are the responsibility of a treating physician.

Methylene Blue May Help Bipolar Depression

We have previously reported on the research by Martin Alda and colleagues that the chemical compound methylene blue had positive effects in patients with bipolar depression. The research was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2016.

We have previously reported on the research by Martin Alda and colleagues that the chemical compound methylene blue had positive effects in patients with bipolar depression. The research was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2016.

Now a new article by Ashley M. Feen and colleagues in the Journal of Neurotrauma reports that methylene blue has an antidepressant-like effect in mice with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Methylene blue reduced inflammation and microglia activation in the animals. Methylene blue reduced levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine Il-1b and increased levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine Il-10.

These findings are of particular interest as many patients with classical depression (and no brain injury) have abnormal levels of these inflammatory markers. It remains to be seen whether methylene blue is more helpful in those patients with elevated inflammatory markers and if levels of the markers can predict treatment response or not.

Methylene blue causes urine to turn blue, so low doses of the compound are used as a placebo. Alda and colleagues reported that the active dose 195mg reduced depression and anxiety significantly more than the placebo dose (15mg) in a 13-week crossover study. In that study, methylene blue was added to lamotrigine which had not had a complete enough effect.

In a 1986 study by G.J. Naylor and colleagues in the journal Biological Psychiatry, patients were treated with either 15mg/day or 300mg/day of methylene blue for one year and crossed over to the other dose in the second year. Participants had significantly less depression during the year of taking the active 300mg/day dose.

The FDA has issued a warning about the danger of a serotonin syndrome if methylene blue is combined with serotonin active agents (presumably because it inhibits MAO-A). Symptoms of the serotonin syndrome can include lethargy, confusion, delirium, agitation, aggression, decreased alertness, and coma. Neurological symptoms, such as jerky muscle contractions, loss of speech, muscle tension, and seizures; or autonomic symptoms, such as fever and elevated blood pressure, are also common. Patients should call their doctor if they are taking a serotonergic psychiatric medication and develop any of the above symptoms.