Changes in brain structure in remitted bipolar patients

Macoveanu et al reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders (2023) that compared to controls that remitted bipolar patients had “a decline in total white matter volume over time and they had a larger amygdala volume, both at baseline and at follow-up time. Patients further showed lower cognitive performance at both times of investigation with no significant change over time….Cognitive impairment and amygdala enlargement may represent stable markers of BD early in the course of illness, whereas subtle white matter decline may result from illness progression.”

Alcohol Use Disorders That Begin Before Age 21 May Cause Lasting Changes to Amygdala

In a 2019 article in the journal Translational Psychiatry, researcher John Peyton Bohnsack and colleagues report that people with alcohol use disorders that began before they were 21 years of age show amygdala changes that people with alcohol use disorders that began after the age of 21 do not appear to have.

In a 2019 article in the journal Translational Psychiatry, researcher John Peyton Bohnsack and colleagues report that people with alcohol use disorders that began before they were 21 years of age show amygdala changes that people with alcohol use disorders that began after the age of 21 do not appear to have.

The amygdalas of those who began abusing alcohol in adolescence showed greater expression of the long non-coding RNA known as BDNF-AS. The increased BDNF-AS was associated with decreased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the amygdala. BDNF protects neurons and is important for learning and memory.

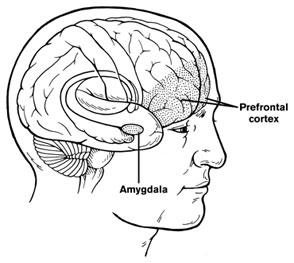

According to Bohnsack and colleagues, “Adolescence is a critical period in brain development and adolescent drinking decreases orbitofrontal cortex activity and increases amygdala activity leading to less executive control, more emotional impulsivity, alterations in decision-making, and [a higher risk of engaging] in risky behaviors and develop[ing] mental health problems later in life.”

Reduced Functional Connectivity of Amygdala Linked to Autism in Pre-School Boys

A 2016 study in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry found that preschool-aged boys with autism have weaker functional connectivity of the amygdala than typically-developing children of the same age. Researchers led by Mark D. Shen used resting-state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure how connected the amygdala was to other regions of the brain in 72 young boys (average age 3.5).

The boys with autism had weaker connectivity between the amygdala and regions linked to social communication, language deficits, and repetitive behaviors. These areas include the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), bilateral temporal lobe, striatum, thalamus, cingulate cortex, and cerebellum.

The weaker the connectivity between these regions, the more severe the boys’ autism symptoms were. They showed impairments in overall cognitive ability and both verbal and nonverbal ability.

Amygdala Hyperactivity Linked to Family History of Depression

In new research presented at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, researcher Tracy Barbour and colleagues revealed that youth with a family history of depression showed more amygdala activation in response to a threat than people without a family history of depression. This amygdala hyperactivity was linked to low resilience to stress and predicted worsening depressive symptoms over the following year.

In the study, 72 non-depressed youth were shown images of cars or human faces or cars that seemed to loom in a threatening way. Brain scans showed increased amygdala activity in participants with a family history of depression compared to those without such a history.

The amygdala is an almond-shaped part of the brain in the temporal lobe that has been linked to emotional reactions and memory, decision-making, and anxiety.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Improves Depression, PTSD by Improving Brain Connectivity

A recent study clarified how cognitive behavioral therapy improves symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The participants were 62 adult women. One group had depression, one had PTSD, and the third was made up of healthy volunteers. None were taking medication at the time of the study. The researchers, led by Yvette Shelive, used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to analyze participants’ amygdala connectivity.

At the start of the study, participants with depression or PTSD showed diminished connectivity between the amygdala and brain areas related to cognitive control, the process by which the brain can vary behavior and how it processes information in the moment based on current goals. The lack of connectivity reflected the severity of the participants’ depression. Twelve weeks of cognitive behavioral therapy improved mood and connectivity between the amygdala and these control regions, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the inferior frontal cortex. These regions also allow for executive functioning, which includes planning, implementation, and focus.

Oxytocin May Reduce PTSD Symptoms

The hormone oxytocin, best known for creating feelings of love and bonding, may help treat post-traumatic stress disorder, since it also reduces anxiety. A study by Saskia B.J. Koch and colleagues that will soon be published in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology reports that a single intranasal administration of oxytocin (at a dose of 40 IU) reduced anxiety and nervousness more than did placebo among police officers with PTSD.

The hormone oxytocin, best known for creating feelings of love and bonding, may help treat post-traumatic stress disorder, since it also reduces anxiety. A study by Saskia B.J. Koch and colleagues that will soon be published in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology reports that a single intranasal administration of oxytocin (at a dose of 40 IU) reduced anxiety and nervousness more than did placebo among police officers with PTSD.

Oxytocin also improved abnormalities in connectivity of the amygdala. Male participants with PTSD showed reduced connectivity between the right centromedial amygdala and the left ventromedial prefrontal cortex compared to other male participants who had also experienced trauma but did not have PTSD. This deficit was corrected in the men with PTSD after they received a dose of oxytocin. Female participants with PTSD showed greater connectivity between the right basolateral amygdala and the bilateral dorsal anterior cingulate cortex than female participants who had experienced trauma but did not have PTSD. This was also restored to normal following a dose of oxytocin.

These findings suggest that oxytocin can not only reduce subjective feelings of anxiety in people with PTSD, but may also normalize the way fear is expressed in the amygdala.

Reduced Cognitive Function and Other Abnormalities in Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

At the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Ben Goldstein described a study of cognitive dysfunction in pediatric bipolar disorder. Children with bipolar disorder were three years behind in executive functioning (which covers abilities such as planning and problem-solving) and verbal memory.

At the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Ben Goldstein described a study of cognitive dysfunction in pediatric bipolar disorder. Children with bipolar disorder were three years behind in executive functioning (which covers abilities such as planning and problem-solving) and verbal memory.

There were other abnormalities. Youth with bipolar disorder had smaller amygdalas, and those with larger amygdalas recovered better. Perception of facial emotion was another area of weakness for children (and adults) with bipolar disorder. Studies show increased activity of the amygdala during facial emotion recognition tasks.

Goldstein reported that nine studies show that youth with bipolar disorder have reduced white matter integrity. This has also been observed in their relatives without bipolar disorder, suggesting that it is a sign of vulnerability to bipolar illness. This could identify children who could benefit from preemptive treatment because they are at high risk for developing bipolar disorder due to a family history of the illness.

There are some indications of increased inflammation in pediatric bipolar disorder. CRP, a protein that is a marker of inflammation, is elevated to a level equivalent to those in kids with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis before treatment (about 3 mg/L). CRP levels may be able to predict onset of depression or mania in those with minor symptoms, and is also associated with depression duration and severity. Goldstein reported that TNF-alpha, another inflammatory marker, may be elevated in children with psychosis.

Goldstein noted a study by Ghanshyam Pandey that showed that improvement in pediatric bipolar disorder was related to increases in BDNF, a protein that protects neurons. Cognitive flexibility interacted with CRP and BDNF—those with low BDNF had more cognitive impairment as their CRP increased than did those with high BDNF.

N-acetylcysteine Reduces Self-Harm, Restores Amygdala Connectivity in Young Women

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an anti-oxidant nutritional supplement that has been found to reduce a wide range of habitual behaviors, including drug and alcohol use, smoking, trichotillomania (compulsive hair-pulling), and gambling. It also improves depression, anxiety, and obsessive behaviors in adults, as well as irritability and repeated movements in children with autism. A new study suggests NAC may also be able to reduce non-suicidal self-injury, often thought of as “cutting,” in girls aged 13–21.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an anti-oxidant nutritional supplement that has been found to reduce a wide range of habitual behaviors, including drug and alcohol use, smoking, trichotillomania (compulsive hair-pulling), and gambling. It also improves depression, anxiety, and obsessive behaviors in adults, as well as irritability and repeated movements in children with autism. A new study suggests NAC may also be able to reduce non-suicidal self-injury, often thought of as “cutting,” in girls aged 13–21.

The open study, presented in a poster by researcher Kathryn Cullen at the 2015 meeting of the Society for Biological Psychiatry, compared magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 15 healthy adolescent girls to scans of 22 girls who had been engaging in self-injury, both before and after this latter group received eight weeks of treatment with N-acetylcysteine. Doses were 1200 mg/day for the first two weeks, 2400mg/day for the next two weeks, and 3600mg/day for the final four weeks. The girls also reported their self-injury behaviors.

Treatment with NAC reduced the girls’ self-injury behaviors. The brain scans showed that NAC also increased resting-state functional connectivity between the amygdala and the insula. Connectivity in this region helps people regulate their emotional responses. At baseline, the girls who engaged in self-harm had had deficient connectivity between the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, insula, and the posterior cingulate cortices compared to the healthy girls, and this improved with the NAC treatment.

Output From the Amygdala Mediates Reward or Fear Memories

People and animals can rapidly learn to associate environmental stimuli with positive or negative outcomes, learning what to approach or avoid as they go through daily life. The amygdala plays a role in this type of emotional learning, which can be disrupted by mood disorders. In new research, Praneeth Namburi and colleagues determined that activity at the synapses in the basolateral amygdala reveals differences in the creation of fear memories and reward memories.

In animals trained with reward and fear conditioning tasks, photostimulation of neurons that then travel from the basolateral amygdala complex to the nucleus accumbens (the brain’s reward center) is positively reinforcing, while photostimulation of neurons that will travel from the basolateral amygdala complex to the centromedial nucleus of the amygdala causes aversion. There are genetic differences between the two types of neurons, including a difference in the gene for the neurotensin-1 receptor. The researchers found that neurotensin, a neuropeptide, modulates glutamate’s effect on neurons, causing some to project to the nucleus accumbens and some to project to the centromedial nucleus of the amygdala.

The researchers wrote that the results “provide a mechanistic explanation, on both a synaptic and circuit level, for how positive and negative associations can be rapidly formed, represented, and expressed within the amygdala.”

Editor’s Note: The amygdala’s creation of opposing outputs may provide clues to the mechanisms behind mania (involving the nucleus accumbens) and depression (involving the centromedial nucleus of the amygdala).

RTMS Can Increase Amygdala Connectivity

Regulation of the amygdala (the brain’s emotional center), particularly through its interaction with the ventral anterior cingulate cortex, has been implicated in the experience of fear in animals, and anxiety and depression in humans. Connectivity between the two structures is critical for emotion modulation. Repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a method of stimulating outer regions of the brain with magnets. Researchers Desmond Oathes and Amit Etkin are investigating whether rTMS can also be used to influence these deeper brain areas, or their interaction with each other.

Regulation of the amygdala (the brain’s emotional center), particularly through its interaction with the ventral anterior cingulate cortex, has been implicated in the experience of fear in animals, and anxiety and depression in humans. Connectivity between the two structures is critical for emotion modulation. Repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a method of stimulating outer regions of the brain with magnets. Researchers Desmond Oathes and Amit Etkin are investigating whether rTMS can also be used to influence these deeper brain areas, or their interaction with each other.

The researchers’ study used single-pulse probe TMS delivered at a rate of 0.4 Hz at 120% of each participant’s motor threshold, targeted at the anterior or posterior medial frontal gyrus on either side of the brain. The researchers also used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the whole brain to observe connectivity between different sections.

RTMS to the right side of the medial frontal gyrus increased connectivity between the amygdala and the ventral anterior cingulate cortex more than stimulation to the left side. Stimulation of the posterior portion of the medial frontal gyrus increased connectivity more than stimulation of the anterior portion.

Editor’s Note: These data indicate that rTMS can alter brain activity in these deeper regions and can influence inter-regional connectivity. This is important because abnormalities in the connectivity of brain regions have increasingly been found in patients with mood disorders. Oathes and Etkin hope that these findings can be applied to others and that rTMS can be used to correct patterns of regional connectivity in the brain in order to improve emotion regulation.