Early Intervention Works in Schizophrenia: Also Needed in Bipolar Disorder

For twenty years, evidence has shown that early intervention can ameliorate many of the adverse consequences of schizophrenia. In a 2018 article in the journal Annual Review of Clinical Psychiatry titled “Transforming the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States: The RAISE Initiative,” Lisa B. Dixon and colleagues described the importance of early intervention in schizophrenia. RAISE stands for Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode. Dixon and colleagues emphasize that shortening the time that a patient’s psychosis goes untreated, which averages 74 months, is critical to achieving good outcomes. In parallel to these consistent findings, researchers of bipolar disorder (including this editor Robert M. Post and colleagues) have found that an increased length of the interval before treatment is initiated in childhood-onset bipolar disorder is associated with a poor outcome in adulthood.

The RAISE program consists of four interventions: personalized psychopharmacology using a computerized decision support system, individual resilience therapy, family psychoeducation and therapy, and supportive employment and education. Compared with patients receiving standard treatments, patients who participated in the RAISE program showed greater improvements on almost all measures, including the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (main outcome), the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, treatment duration, and engagement in work and school. Moreover, the improvements were more substantial among patients with a shorter duration of untreated psychosis.

Editor’s Note: These findings are of great importance in their own right, but they also have great implications for treatment and research efforts in bipolar disorder. A 2013 randomized study by Lars Kessing and colleagues published in the British Journal of Psychiatry found that in bipolar patients hospitalized for a first or second episode of mania, two years of comprehensive treatment with psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and illness education that included mood monitoring and early symptom recognition was vastly superior to typical treatment, and this held true even six years later. In a 2014 article in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry and a 2016 article in the journal Bipolar Disorders, researcher Jan Marie Kozicky and colleagues reported that in patients hospitalized with a first episode of mania, cognitive functioning and brain imaging abnormalities, respectively, returned to normal over the next year only if the patients experienced no further mood episodes. The message is clear: we must treat the first episode of mania comprehensively to avoid long-term deterioration, which occurs as a function of the number of episodes of mania or depression a patient experiences. However, this early multimodal approach is rarely taken in the US.

In schizophrenia, Dixon and colleagues noted that: “After the RAISE study reports were made available, Congress allocated additional funding to the community mental health …program, leading to growth in the number of…programs across the United States; they were expected to reach 48 states in 2018.”

The contrast between these efforts in schizophrenia and their virtual absence in bipolar disorder is incomprehensible and tragic. Studies in early schizophrenia have been funded for 25 years, while almost none have been funded in bipolar disorder, even in recent years. Community mental health programs for early schizophrenia will soon exist in 48 states; for patients with bipolar disorder there are no programs available in any state that I am aware of. The incidence of bipolar is about three times that of schizophrenia, and the long-term outcomes are often as devastating in bipolar disorder as in schizophrenia. There is a high incidence of drug abuse; social, educational and occupational deficits; and suicide in bipolar disorder. Early intervention with the many safe supplements, nutraceuticals, and well-tolerated drugs that are currently available to adult patients should be studied in young people with bipolar disorder, but such studies neither being funded nor conducted.

The reality is that childhood-onset bipolar disorder is poorly recognized and treated in the US, largely because of a paucity of treatment-related studies and knowledge about the best options for these young patients. If a reader of the BNN knows how to influence advocacy groups, leaders in the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), or influential politicians, it would be useful to take the initiative in bringing some of these deficits and disparities to their attention. Something must be done; ideas about how to do it are welcome. My own efforts to get funding for a childhood-onset bipolar research network in collaboration with such luminaries in the field as David Miklowitz (UCLA), Kiki D. Chang (Stanford University), Boris Birmaher (University of Pittsburg), Benjamin Goldstein (Stonybrook Research Institute), Eric Youngstrom (UNC, Chapel Hill), Soledad Romero (Hospital Clinic of Barcelona), and Josefina Castro Fornieles (University of Barcelona) have not been successful. We will keep trying, but the field needs to reach beyond the many investigators who are advocating for more treatment research to other people with more influence.

Genetic Markers of Response to Lithium

At the 5th Biennial Conference of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders and the 67th Annual Meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, John Kelsoe presented his research on personalized pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder, describing genetic predictors of response to lithium.

At the 5th Biennial Conference of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders and the 67th Annual Meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, John Kelsoe presented his research on personalized pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder, describing genetic predictors of response to lithium.

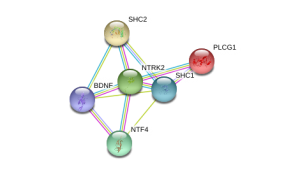

In his research Kelsoe found that a variant of the gene that codes for neurotrophic receptor type II (NTRK2), the receptor for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), was associated with good response to lithium in patients with a family history of bipolar disorder or a history of euphoric mania. The “T” allele of rs1387923 was associated with better response to lithium retrospectively, and these results were replicated in a prospective study.

Editors Note: These data are among the first to indicate that genetic information could be used to make treatment decisions. Lithium increases BDNF and neurogenesis, thus it makes some sense that a variation in the BDNF receptor would affect clinical responsiveness to lithium.

In a similar vein, Janusz K. Rybakowski reported at the Society of Biological Psychiatry meeting on another possible predictor of long-term excellent response to lithium in bipolar disorder. Due to normal genetic variation, different people have different versions of BDNF. Rybakowski found that the patients with a version of BDNF known as Val66Val who had bipolar disorder performed significantly better on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, which evaluates abstract reasoning. However, he found that patients with a methionine amino acid in the place of one of the valine amino acids (resulting in a Val66Met allele, which is associated with minor cognitive difficulties) showed significantly better response to preventative treatment with lithium. It is noteworthy that these excellent lithium responders also performed better on a complex neuropsychological battery than those who were less good responders to lithium. The good responders’ performance on these tests was not different from healthy controls.

Editor’s Note: These data add to the possibility that prediction of lithium response is linked to common gene variations in neuroprotective factors or their receptors. It is interesting that the patients with the Val66Met allele, which works less efficiently, show the best long-term response to lithium. This is consistent with the view that lithium, which increases BDNF, is most effective in those who have a sluggish functioning of their BDNF due to having the Met allele. As we have written before, those with the Met allele have slight decrements in working memory, and in animal models, those with the Met allele show deficits in long-term potentiation (LTP), which suggest problems with long-term memory. Thus, using lithium to increase BDNF function in those with a “sluggish” variation in their BDNF makes sense and may ultimately be clinically useful.