Low Oxytocin Linked to Depression in Moms

At a panel at the 2015 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, researcher Andrea Gonzales described her team’s study of mechanisms related to postpartum depression and the bonding hormone oxytocin. In the study of 26 women at eight months postpartum, the team examined whether there were connections between a mother’s levels of oxytocin at baseline and after interacting with her child, her mood symptoms, and whether she was mistreated in childhood.

Those women who scored low on a history of maltreatment in childhood had bigger increases in oxytocin in their blood and saliva after interacting with their children. Those with high trauma scores but low levels of depression also saw big boosts in oxytocin after seeing their children. Those women who had both a history of trauma in childhood and current depressive symptoms did not get as big a boost of oxytocin after interacting with their children.

Gonzales and colleagues concluded that postpartum depression is linked to dysregulation of oxytocin levels, and that a history of trauma in the mother’s childhood can make this worse.

The researchers hope that these findings may make it easier to identify which women are at risk for postpartum depression, and that they may point to possible treatments in the future.

Postpartum depression is a problem for about 13% of mothers in the year after they give birth, and mother-child bonding may be disturbed if a mother is depressed. One way to foster better bonding between a depressed mother and her newborn is to use video feedback. A mother views video of herself interacting with her child while a trained professional helps her identify opportunities for greater physical contact.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids Prevent Conversion to Psychosis

A new long-term study of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for psychosis prevention shows that almost seven years after a 3-month stint of receiving these dietary supplements daily, adolescents and young adults at high risk for psychosis showed fewer symptoms of conversion to full-blown psychosis than those who received placebo during the same period.

A new long-term study of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for psychosis prevention shows that almost seven years after a 3-month stint of receiving these dietary supplements daily, adolescents and young adults at high risk for psychosis showed fewer symptoms of conversion to full-blown psychosis than those who received placebo during the same period.

The research team, led by Paul Amminger, originally found that among 81 youth (mean age 16.5) at high risk of developing psychosis due to their family histories, the 41 who received 12 weeks of daily supplementation with 700mg of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) omega-3s and 480 mg of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) omega-3s showed reduced likelihood of conversion to psychosis one year later than the 40 who received placebo.

The team followed up an average of 6.7 years later with 71 of the original 81 participants. Among those who had received the omega-3 intervention, 9.8% had developed psychosis. Among the placebo group, 40% had developed psychosis, and they had done so earlier.

In addition, the omega-3 participants were better functioning, they had required less antipsychotic medication, and they had lower rates of any psychiatric disorder than the placebo group.

Amminger wrote in the journal Nature Communications, “Unlike antipsychotics, fish oil tablets have no side effects and arent’s stigmatizing to patients.”

Editor’s Note: Because of their lack of side effects, a good case can be made for omega-3 fatty acids for patients at high risk for psychosis. The novel thing about this study is that short-term treatment with omega-3 fatty acids had preventive effects almost 7 years later.

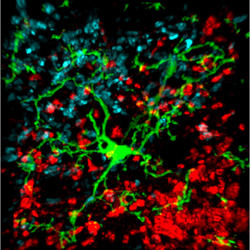

Blood and Now Brain Inflammation Linked to Depression

There is growing evidence of a link between inflammation of depression. At the 2015 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, researcher Jeff Meyer summarized past studies on inflammatory markers. These are measurements, for example of certain proteins in the blood, that indicate the presence of inflammation in the body.

There is growing evidence of a link between inflammation of depression. At the 2015 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, researcher Jeff Meyer summarized past studies on inflammatory markers. These are measurements, for example of certain proteins in the blood, that indicate the presence of inflammation in the body.

Common inflammatory markers that have been linked to depression include IL-6, TNF-alpha, and c-reactive protein. At the meeting, Meyer reviewed the findings on each of these. Twelve studies showed that IL-6 levels are elevated in the blood of patients with depression. Four studies had non-significant results of link between IL-6 and depression, and Meyer found no studies indicating that IL-6 levels were lower in those with depression. Similarly, for TNF-alpha, Meyer found 11 studies linking elevated TNF-alpha with depression, four with non-significant results, and none showing a negative relationship between TNF-alpha and depression. For c-reactive protein, six studies showed that c-reactive protein was elevated in people with depression, six had non-significant results, and none indicated that c-reactive protein was lower in depressed patients.

Most studies that have linked inflammation to depression have done so by measuring inflammatory markers in the blood. It is more difficult to measure inflammation in the brain of living people, but Meyer has taken advantage of new developments in positron emission tomography (PET) scans to measure translocator protein binding, which illustrates when microglia are activated. Microglial activation is a sign of inflammation. Translocator protein binding was elevated by about 30% in the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and insula in study participants who showed symptoms of a major depressive episode compared to healthy control participants. The implication is that the depressed people with elevated translocator protein binding have more brain inflammation, probably via microglial activation.

The antibiotic minocycline reduces microglial activation. It would be interesting to see if minocycline might have antidepressant effects in people with depression symptoms and elevated translocator protein binding.

Most SSRIs Free of Birth Defect Risk Early in Pregnancy, Fluoxetine and Paroxetine are Exceptions

A large study of women who took selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants in the month before pregnancy and throughout the first trimester suggests that there is a smaller risk of birth defects associated with SSRI use than previously thought, though some risks were elevated in women who took paroxetine or fluoxetine.

The 2015 study, by Jennita Reefhuis and colleagues in the journal BMJ, investigated the drugs citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, and examined birth defects that had previously been associated with SSRI use in smaller studies. The participants were 17,952 mothers of infants with birth defects and 9,857 mothers of infants without birth defects who had delivered between 1997 and 2009.

Sertraline was the most commonly used SSRI among the women in the study. None of the birth defects included in the study were associated with sertraline use early in pregnancy. The study found that some birth defects were 2 to 3.5 times more likely to occur in women who had taken fluoxetine or paroxetine early in their pregnancies.

Five different birth defects, while uncommon, were statistically linked to paroxetine use: anencephaly (undersized brain), heart problems including atrial septal defects and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction defects, and defects in the abdominal wall including gastroschisis and omphalocele. Two types of birth defects were associated with fluoxetine use: right ventricular outflow tract obstruction defects and craniosynostosis (premature fusion of the skull bones). Absolute incidence of these defects was also low.

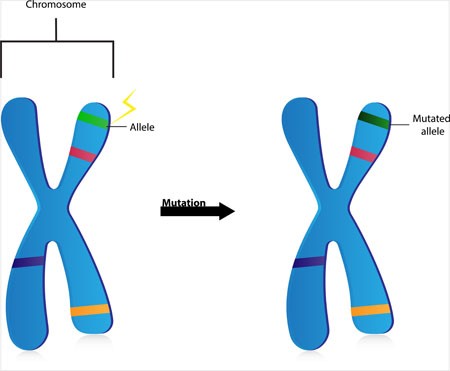

A Note on Genetic Inheritance

Genetic inheritance is not everything, according to J. Craig Venter, pioneering genetic scientist responsible for sequencing the human genome in 2001:

“Human biology is actually far more complicated than we imagine. Everybody talks about the genes that they received from their mother and father, for this trait or the other. But in reality, those genes have very little impact on life outcomes. Our biology is far too complicated for that and deals with hundreds of thousands of independent factors. Genes are absolutely not our fate. They can give us useful information about the increased risk of a disease, but in most cases they will not determine the actual cause of the disease, or the actual incidence of somebody getting it. Most biology will come from the complex interaction of all the proteins and cells working with the environmental factors, not driven directly by the genetic code.”

Verbal Abuse in Childhood, Like Physical and Sexual Abuse, Linked to Earlier Onset and More Difficult Course of Bipolar Disorder

Earlier research has shown that childhood adversity is linked to earlier age of onset of bipolar disorder and more difficult course of illness. Physical and sexual abuse are associated with both earlier age of onset and more difficulties such as anxiety disorders and substance abuse. Now, new research by this editor (Robert M. Post) and colleagues links verbal abuse (even in the absence of physical and sexual abuse) to earlier onset of bipolar disorder and to more severe and complicated course of illness.

The study, published in the journal Bipolar Disorders, was based on the self-reports of 634 adult outpatients with bipolar disorder at four sites in the US. These participants were interviewed about their history of illness and the frequency of adverse events they experienced in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, including physical, sexual, and verbal abuse. Twenty-four percent of these participants reported having experienced verbal abuse occasionally or frequently in childhood, but not other forms of abuse, while another 35% had a history of verbal abuse as well as physical or sexual abuse, for a total of 59% with a history of verbal abuse.

The greater the frequency of verbal abuse in childhood, the earlier the average age of onset of bipolar disorder. Participants with no history of abuse had a mean age of onset of 20.6 years, but verbal abuse by itself reduced the mean age of onset to 16.5 years, and verbal abuse plus sexual abuse reduced the mean age of onset to 15.3 years. (The mean age of onset for participants who experienced sexual abuse alone was 17.5 years.) It was impossible to determine the combined effect of verbal and physical abuse because verbal abuse was almost always present when physical abuse occurred. For the 14% of the participants who had experienced verbal, physical, and sexual abuse in childhood, the mean age of onset of bipolar disorder was 13.1 years.

Those who were verbally (but not physically or sexually) abused in childhood had more anxiety disorders, drug abuse, and rapid cycling than those who were not abused, but not more alcohol abuse. Those who were verbally abused also showed increasing severity of illness, including increased frequency of cycling.

Genetics can also play a role. Having a parent with a mood disorder also contributed to an earlier age of onset of bipolar disorder.

Editor’s Note: Researcher David J. Miklowitz and colleagues have shown that family focused therapy (FFT), which emphasizes illness education and communication enhancement within the family, is more effective than treatment as usual for children with a family history of bipolar disorder and a diagnosis of depression, cyclothymia, or bipolar not otherwise specified (BP NOS).

FFT was particularly effective in reducing symptoms in children from families with high expressed emotion, suggesting that this kind of family-based intervention could reduce levels of verbal abuse.

“De Novo” Mutations in Dozens of Genes Cause Autism

Two studies that incorporated data from more than 50 labs worldwide have linked mutations in more than 100 different genes to autism. Scientists have a high level of statistical confidence that mutations in about 60 of those genes are responsible for autism. So-called de novo mutations (Latin for “afresh”) do not appear in the genes of parents without autism, but arise newly in the affected child. The mutations can alter whether the genes get “turned on” or transcribed (or not), leading to disturbances in the brain’s communication networks.

The studies led by Stephan Sanders and Matthew W. State appeared in the journal Nature in late 2014. The identified genes fall into three categories. Some affect the formation and function of synapses, where messages between neurons are relayed. Others affect transcription, the process by which genes instruct cells to produce proteins. Genes in the third category affect chromatin, a sort of packaging for DNA in cells.

Before the new studies, only 11 genes had been linked to autism, and the researchers involved expect to find that hundreds more are related to the illness.

Editor’s Note: This new research explains how autism could be increasing in the general population even as most adults with autism do not have children. It should also put to rest the idea, now totally discredited, that ingredients in childhood immunizations cause autism. It is clearer than ever that kids who will be diagnosed with autism are born with these mutations.

With these genetic findings, the search for new medications to treat this devastating illness should accelerate even faster.

Bottom line: Childhood immunizations don’t cause autism, newly arising mutations in the DNA of parents’ eggs or sperm do. However, parental behavior could put their children and others at risk for the measles and other serious diseases if they do not allow immunizations. The original data linking autism to immunization were fraudulent, and these new data on the genetic origins of autism provides the best hope for future treatments or prevention.

Inability to Balance on One Leg May Indicate Stroke Risk

A balance test may indicate declining cognitive health and risk for stroke. Researchers led by Yasuharu Tabara had previously found that balancing on one leg became more difficult for people with age. Now the same team has found that this type of postural instability is associated with decreases in cognitive functioning and with risk of stroke. Fourteen hundred participants with an average age of 67 were challenged to balance on one leg for up to 60 seconds. They also completed computer surveys, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and a procedure to measure the thickness of their carotid artery. Those who could not balance on one leg for 20 seconds or longer were more likely to have cerebral small vessel disease.

Editor’s Note: Whether exercise would reverse this vulnerability remains to be seen, but lots of other data suggest the benefit of regular (even light) exercise on general health.

Mental Illness Associated with 10 Years Lost Life Expectancy

Severe mental illness is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. Recently researchers led by E.R. Walker performed a meta-analysis of all cohort studies comparing people with mental illness to non-ill populations. They used five databases to find 203 eligible studies from 29 countries. Their findings, published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry in 2015, show that people with mental illness have a mortality rate 2.22 times higher than people without mental illness. People with mental illness lose a potential 10 years of life compared to those without severe mental disorders. The researchers estimated that 14.3% of deaths worldwide are attributable to mental illness.

Editor’s Note: Comorbid cardiovascular illness accounts for a large part of the disparity in life expectancy between people with and without mental illness. Those at risk for serious mental illness should pay close attention to their cardiovascular as well as psychiatric risk factors.

Subthreshold Episodes of Mania Best Predictor of Bipolar Disorder in Children

Relatively little attention has been paid to the children of a parent with bipolar disorder, who are at risk not only for the onset of bipolar disorder, but also anxiety, depression, and multiple other disorders. These children deserve a special focus, as on average 74.2% will receive a major (Axis 1) psychiatric diagnosis within seven years.

New research published by David Axelson and colleagues in the American Journal of Psychiatry describes a longitudinal study comparing children who have a parent with bipolar disorder to demographically matched children in the general public. Offspring at high risk for bipolar disorder because they have a parent with the disorder had significantly higher rates of subthreshold mania or hypomania (13.3% versus 1.2%) or what is known as bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BP-NOS); manic, mixed, or hypomanic episodes (9.2% versus 0.8%); major depressive episodes (32.0% versus 14.9%); and anxiety disorders (39.9% versus 21.8%) than offspring of parents without bipolar disorder. Subthreshold episodes of mania or hypomania (those that resemble but do not meet the full requirements for bipolar disorder in terms of duration) were the best predictor of later manic episodes. This finding was observed prospectively, meaning that patients who were diagnosed with manic episodes during a follow-up assessment were likely to have been diagnosed with a subthreshold manic or hypomanic episode during a previous assessment.

The study included 391 children (aged 6–18) of at least one bipolar parent, and compared these to 248 children of parents without bipolar disorder in the community. The participants took part in follow-up assessments every 2.5 years on average, for a total of about 6.8 years. Each follow-up assessment included retrospective analysis of symptoms that had occurred since the previous assessment.

In addition to having more subthreshold manic or hypomanic episodes; manic, mixed, or hypomanic episodes; and major depressive episodes, the high-risk children also showed more non-mood-related axis 1 disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), disruptive behavior disorders, and anxiety disorders than the children of parents without bipolar disorder. Axelson suggested that monitoring for these symptoms may help with early identification and treatment.

Children with a bipolar parent were diagnosed with bipolar spectrum disorders at rates of 23% compared to 3.2% in the comparison offspring. Mean age of onset of mania or hypomania in the high-risk offspring was 13.4 years. Of those offspring who had a manic episode, more than half had the episode before age 12, with the earliest occurring at age 8.1.

Compared to previous studies of children of parents with bipolar disorder, this study found that the mean age of onset of manic or hypomanic episodes was younger, possibly because other studies did not include young children. Another new finding was that major depressive episodes were risk factors for mania and hypomania but did not always precede the onset of mania or hypomania in the high-risk offspring.

Parents of children who are at high risk for developing bipolar spectrum disorders should be aware of the common precursors to mania—subthreshold manic or hypomanic symptoms and non-mood disorders—and make sure that clinicians assess for these symptoms and differentiate them from the symptoms of depression or other disorders.

Editor’s Note: In Axelson’s study, 74.2% of the offspring of a bipolar parent suffered a major (Axis I) psychiatric disorder. However, 48.4% of the offspring from the comparison group of community controls also had an Axis 1 psychiatric disorder. These high rates of illness and dysfunction indicate the importance of monitoring a variety of symptom areas and getting appropriate evaluation and treatment in the face of symptoms that are associated with impairment in both high risk children and in the general population.

One way of doing this is for parents to join our new Child Network, a study collecting information about how children at risk for bipolar disorder or with symptoms of bipolar disorder are being treated in the community and how well they are doing. Parents rate their children on a weekly basis for depression, anxiety, ADHD, oppositionality, and mania-like symptoms. Parents will be able to produce a longitudinal chart of their children’s symptoms and response to treatment, which may assist their child’s physician with early detection of illness and with treatment. See here for more information and to access informed consent documents.