A Possible Explanation for Vitamin D’s Antidepressant Effects

Vitamin D plays an important role in the nervous system, regulating the production of neurotrophins, calcium channels, and calcium binding proteins, and it may have antidepressant effects. Researchers are learning more about how the vitamin’s effects take place.

Vitamin D plays an important role in the nervous system, regulating the production of neurotrophins, calcium channels, and calcium binding proteins, and it may have antidepressant effects. Researchers are learning more about how the vitamin’s effects take place.

At the 2014 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Yilmazer et al. reported that vitamin D treatment increased the production of glia-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF). Neurotrophins like GDNF enhance the survival and growth of neurons. Since other neurotrophins (i.e. brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEG-F)) are low in depression, vitamin D’s effect on GDNF could be important to its antidepressant effects.

Another Blocker of Glutamate Receptor Function with Rapid Antidepressant Effects

Certain drugs such as ketamine and memantine that work by blocking activity at the NMDA receptor for the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate have antidepressant effects. D-cycloserine is a drug that has a related mechanism and is being studied as an antidepressant. At high doses the drug acts as an antagonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor, blocking glycine’s ability to facilitate glutamate transmission through the receptor.

Joshua Kantrowitz, a researcher at Columbia University, reported at a recent scientific meeting that the rapid-onset antidepressant effects of D-cycloserine could be maintained for eight weeks. Similar findings were published in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 2010 and were reported in another study by Uriel Heresco-Levy in a 2013 article in the Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain and is important for the development of long-term memory. However, glutamate overactivity may contribute to depression. Decreasing this overactivity (with ketamine, memantine, or D-cycloserine) may produce antidepressant effects.

More Evidence That Regular Antidepressants Do Not Work in Bipolar Depression

Psychiatrists most commonly prescribe antidepressants for bipolar depression, but mounting evidence shows that the traditional antidepressants that are effective in unipolar depression are not effective in bipolar disorder. At the 2013 meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, researcher Jessica Lynn Warner reported that among 377 patients with Bipolar I Disorder who were discharged from a hospital, those who were prescribed an antidepressant at discharge were just as likely to be remitted for a new depression than those not given an antidepressant.

The average time to readmission also did not differ across the two groups and was 205 +/- 152 days. Those patients prescribed the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) drug venlafaxine (Effexor) were three times more likely to be readmitted than those not prescribed antidepressants.

These naturalistic data (generated from observations of what doctors normally do and information in the hospital’s clinical notes) resemble those from controlled studies. In the most recent meta-analysis of antidepressants in the treatment of bipolar depression (by researchers Sidor and MacQueen), there appeared to be no benefit to adding antidepressants to ongoing treatment with a mood stabilizer over adding placebo. Randomized studies by this editor Post et al. and Vieta et al. have shown that venlafaxine is more likely to bring about switches into mania than other types of antidepressants such as bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

In addition, a naturalistic study published by this editor Post et al. in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry in 2012 showed that the number of times antidepressants were prescribed prior to a patient’s entrance into a treatment network (the Bipolar Collaborative Network) at an average age of 40 was related to their failure to achieve a good response or a remission for a duration of at least six months during prospective treatment.

Editor’s Note: Antidepressants are still the most widely used treatments for bipolar depression, and their popularity over more effective treatments (mood stabilizers and some atypical antipsychotics) probably contributes to the fact that patients with bipolar disorder receiving typical treatment in their communities spend three times as much time in depressions than in manic episodes. Using other treatments first before an antidepressant would appear to do more to prevent bipolar depression. These treatments include mood stabilizers (lithium, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and valproate); the atypical antipsychotics that are FDA-approved for monotherapy in bipolar depression, lurasidone (Latuda) and quetiapine (Seroquel); and the combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine that goes by the trade name Symbiax.

Evidence from several sources suggests that the SNRI venlafaxine may be a risk factor for switches into mania and lead to re-hospitalizations. Other data suggest that in general, in bipolar depression, augmentation treated with antidepressants should be avoided in several cases: in childhood-onset bipolar depression, in mixed states, and in those with a history of rapid cycling (4 or more episodes per year).

RTMS in Depression: Positive Effects in Long-Term Follow-Up

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non-invasive treatment that uses a rapidly changing magnetic field to target neurons, creating a weak electric current. It is used to treat depression, strokes, and other neurological and psychiatric conditions. At the 2013 meeting of the American Psychiatic Association (APA), researcher Linda L. Carpenter reported on new findings about the long-term effects of rTMS.

In the new research, which was led by Mark Andrew Demitrack, 307 patients with unipolar depression who had not responded well to previous antidepressant treatment were given rTMS. They were treated in 43 different clinical practices and administered rTMS according to their evaluating physician, following FDA guidelines. Of the 307 patients who began the study, 264 benefited from initial treatments with rTMS, were tapered off rTMS, and agreed to participate in a one-year follow-up period, by the end of which 68% had improved and 40.4% had achieved complete remission as measured by the Clinical Global Impressions scale for severity of illness.

However, some study participants (30.2%) had worsened by the first follow-up assessment at the 3-month mark, and rTMS had to be re-introduced.

New Drug Produces Rapid-Onset Antidepressant Effects

We have previously summarized studies on ketamine, which when given intravenously can bring about rapid-onset antidepressant effects. Ketamine is a full antagonist (or a blocker) of the glutamate NMDA receptors. Another drug currently in development may work in a related way.

We have previously summarized studies on ketamine, which when given intravenously can bring about rapid-onset antidepressant effects. Ketamine is a full antagonist (or a blocker) of the glutamate NMDA receptors. Another drug currently in development may work in a related way.

At a recent scientific meeting, researcher Sheldon Preskorn showed that the compound GLYX-13, a partial agonist at the glycine binding site of the NMDA receptor (meaning it allows partial function of the glycine receptors that aid NMDA receptor function), exerts rapid antidepressant effects like the full antagonist ketamine when administered intravenously compared to placebo. GLYX-13 allows about 25% of the receptor activity of the full agonists glycine or D-serine, and thus might result in a 75% inhibition of NMDA receptor function.

GLYX-13 did not induce any psychotomimetic effects (like delusion or delirium), which are possible with the full NMDA antagonist ketamine. The effects of GLYX-13 appeared within 24 hours, lasted at least 6 days, but were gone by day 14.

Editor’s Note: Long-term effectiveness of ketamine for treatment of depression is unclear, but in addition to its potential psychotomimetic effects, it can also be abused. Whether GLYX-13 may be easier to use, longer-lasting, or safer for longer-term clinical effectiveness remains a key question.

New Findings On IV Ketamine For Treatment-Resistant Depression

We’ve written before about the rapid-onset antidepressant effects of ketamine, an anesthetic that is used in human and veterinary medicine. At lower doses, intravenous (IV) ketamine can induce antidepressant effects in both unipolar and bipolar depressed patients. When doses of 0.5mg/kg are infused over a period of 40 minutes, antidepressant effects appear within two hours but are short-lived, typically lasting only three to five days. Results have been consistent across studies at Yale University, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and the National Institute of Mental Health. So far, clinical use has been limited by the short duration of the effects and the required presence of an anesthesiologist, which can be prohibitively expensive for many patients.

In a cover story in the January 2013 issue of Psychiatric Times, Arline Kaplan reviewed new findings about ketamine. The drug is a high-affinity, noncompetitive NMDA-glutamate receptor antagonist. It is not yet FDA-approved for use in depression.

According to a recent article by Murrough and Charney, response rates to ketamine are around 54% and the drug “appears to be effective at reducing the range of depressive symptoms, including sadness, anhedonia [the loss of ability to experience pleasure], low energy, impaired concentration, negative cognitions, and suicidal ideation.”

David Feifel, Director of the Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Medicine Program at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), instituted a program there in which patients can receive treatment with ketamine for clinical purposes (rather than for research) after signing detailed informed consent forms and being warned that the treatment is not yet approved for depression and that its effects may be temporary. The UCSD Medical Center’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, with the support of the anesthesiology department, agreed that nurses may administer the ketamine in an outpatient setting, making the procedure more affordable.

There is still the question of how to make ketamine’s effects last. Read more

No Relationship Between SSRIs in Pregnancy and Stillbirths or Neonatal Mortality

Much has been written about the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants during pregnancy. In a review of 920,620 births in Denmark (1995 to 2008) that Jimenez-Solem published this year in the American Journal of Psychiatry, no link was found between any of the SSRIs used in any trimester and risk of stillbirth or neonatal mortality. The only exception was a possible association of three-trimester exposure to citalopram and neonatal mortality.

Much has been written about the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants during pregnancy. In a review of 920,620 births in Denmark (1995 to 2008) that Jimenez-Solem published this year in the American Journal of Psychiatry, no link was found between any of the SSRIs used in any trimester and risk of stillbirth or neonatal mortality. The only exception was a possible association of three-trimester exposure to citalopram and neonatal mortality.

Editor’s Note: These new data may be of importance to women considering antidepressant continuation during pregnancy when there is a high risk for a depressive relapse. A maternal depressive episode (like other stressors such as anxiety or experiencing an earthquake) during pregnancy does convey adverse effects to the child, so appropriate evaluation of the risk/benefit ratio or staying on an antidepressant through a pregnancy is important.

Despite the FDA Warning to the Contrary: Antidepressants Do Not Increase Suicidality

In 2007, the FDA began labeling antidepressants with a warning that patients aged 18-24 were at risk for increased suicidality during the first weeks of treatment. New evidence shows antidepressants actually have beneficial effects on suicide risk in adults. A study of all published and unpublished data on the SSRI fluoxetine (Prozac) and the SNRI venlafaxine (Effexor) published in 2012 by Gibbons et al. in the Archives of General Psychiatry showed that these antidepressants substantially reduced suicidal thoughts and behavior in adults and produced no increase in suicidal thoughts or behavior in children and adolescents.

The protective effect on suicidality in adults was mediated by mood, i.e. the patients’ mood improved and they became less suicidal. Children’s mood also improved on the antidepressants, but their risk of suicidal ideation did not change.

Editor’s Note: These are important findings. When the FDA box warning on antidepressants and suicidal ideation appeared, antidepressant treatment of youth decreased without an accompanying increase in psychotherapy, and the actual suicide rate in youth increased.

We now know that childhood-onset depression carries a bigger risk for a poor outcome in adulthood than adult-onset illness. In parallel, greater numbers of depressions are associated with more impairment, disability, cognitive dysfunction, medical comorbidities, treatment resistances, and neurobiological abnormalities.

It is important to treat illness in young people in order to prevent these difficulties, and the suicide warning should not deter the use of antidepressants. Patients should be careful about suicidal ideation in the first several months after starting an antidepressant, as other data suggest that this is a time of slightly increased risk of suicidal thoughts in children and adolescents.

It Appears Antidepressants and Stimulants Do Not Hasten the Onset of Bipolar Disorder in Children

It is a common clinical assumption that early treatment of depression with antidepressants may be a risk factor for hastening the onset of subsequent bipolar disorder. Accumulating evidence indicates that this may not be the case. At a symposium at the 2012 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) researchers in the field shared the latest findings on antidepressant-induced manic symptoms in youth (AIMS), and there was a surprising consensus that antidepressants do not increase the risk of subsequent bipolar disorder onset when used for the treatment of childhood-onset depression.

Symposium speakers Kiki Chang, Melissa P. DelBello, and David Axelson all agreed that antidepressant treatment was not a risk factor for bipolar disorder.

DelBello shared data from a study in which antidepressant treatment was associated with a lower likelihood of mania during follow-up. Antidepressants were typically discontinued if the patient switched into manic-like symptoms or increased irritability or aggression. These symptoms tended to occur in children who were younger, who had a smaller volume of the amygdala, and in those who had a positive family history for bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives.

Axelson indicated that his data represented only a “bird’s-eye view,” but suggested that antidepressants do not cause or hasten the onset of bipolar disorder when used for treating depression in children. He also reported results from a naturalistic study in which stimulants also did not increase the risk of subsequent bipolarity.

Several of the presenters discussed how they would treat children with an early-onset depression when there is a family history of bipolar disorder. Read more

Developing Rapid Onset Antidepressant Drugs That Act at the NMDA Receptor

For several years, researchers have been exploring potential rapid-acting treatments for unipolar and bipolar depression. Intravenous ketamine has the best-replicated results so far. A slow infusion of ketamine (0.5mg/kg over 40 minutes) produces a rapid onset of antidepressant effects in only a few hours, but the improved mood lasts only 3-5 days.

For several years, researchers have been exploring potential rapid-acting treatments for unipolar and bipolar depression. Intravenous ketamine has the best-replicated results so far. A slow infusion of ketamine (0.5mg/kg over 40 minutes) produces a rapid onset of antidepressant effects in only a few hours, but the improved mood lasts only 3-5 days.

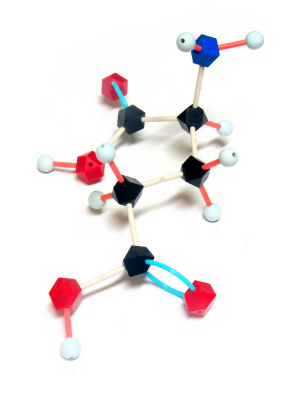

Ketamine blocks the receptors of the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, glutamate. Glutamate is released from nerve endings and travels across the synapse to receptors on the next cell’s dendrites. There are multiple types of glutamate receptors at the dendrites, and ketamine blocks one called the NMDA receptor, which allows calcium ions to enter the cell.

Some downsides to ketamine are the brief duration of its effectiveness and its dissociative side effects. The search is on for other drugs that are free from these side effects and that could extend the duration of rapid-onset antidepressant effects.

At the 2012 meeting of the International Congress of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP), Mike Quirk of the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca reviewed data on the intricacies of the glutamate NMDA receptor blockade and discussed the potential of AZD6765, an NMDA receptor blocker he and his colleagues have been researching.

The more the NMDA receptor is blocked, the more psychomimetic it becomes, meaning it produces hallucinations and delusions. For example, phencyclidine (PCP or angel dust) is a potent NMDA receptor blocker and psychosis inducer. For antidepressant purposes, a less complete or less persistent NMDA receptor blockade is desired. Read more