Management of Unipolar and Bipolar Depression During Pregnancy

At the Maryland Psychiatric Research Society’s continuing medical education conference in November, Lauren Osbourne, Assistant Director of the Women’s Mood Disorders Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital, gave a presentation on the management of mood and anxiety during pregnancy and lactation. She had a number of important ideas for physicians and patients to consider in their decision-making process.

At the Maryland Psychiatric Research Society’s continuing medical education conference in November, Lauren Osbourne, Assistant Director of the Women’s Mood Disorders Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital, gave a presentation on the management of mood and anxiety during pregnancy and lactation. She had a number of important ideas for physicians and patients to consider in their decision-making process.

According to Osbourne, 60%-70% of pregnant women with unipolar depression who discontinue their antidepressants relapse. Of those with bipolar disorder who discontinue their mood stabilizers, 85% relapse, while 37% of those who stay on their medications relapse.

Something to consider when deciding whether to continue medication while pregnant is that depression in pregnancy carries its own risks for the fetus. These include preterm delivery, low birth weight, poor muscle tone, hypoactivity, increased cortisol, poor reflexes, and increased incidence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other behavioral disorders.

The placenta makes an enzyme 11-BHSD2 that lowers the stress hormone cortisol in the baby. However, this enzyme is less active in depression, exposing the fetus to higher levels of cortisol.

Thus, the decision about whether to continue medications during pregnancy should consider the risks to the fetus of both the mother’s depression and the mother’s medications.

Most antidepressants are now considered safe during pregnancy. There have been reports of potential problems, but these data are often confounded by the fact that women with more severe depression are more likely to require antidepressants, along with other risk variables such as smoking or late delivery (after 42 weeks). When these are accounted for by using matched controls, the apparent risks of certain antidepressants are no longer significant. This includes no increased risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension, autism, or cardiac malformations.

There may be a possible increased risk of Neonatal Adaption Syndrome (NAS) in the first weeks of life in babies who were exposed to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants in the third trimester. This syndrome presumably results from antidepressant withdrawal, and can include respiratory distress, temperature changes, decreased feeding, jitteriness/irritability, floppiness or rigidity, hypoglycemia, and jaundice. There is not yet a robust literature on the syndrome, but Osbourne suggested that it disappears within 2 weeks of birth.

In her practice, Osbourne prefers to prescribe sertraline, which has the best safety data, along with fluoxetine. Sertraline is also OK for breastfeeding. There is less data on bupropion, but it also appears to be safe during pregnancy. Endocrine and enzyme changes in pregnancy typically cause a 40% to 50% decrease in concentrations of antidepressants, so doses of antidepressants typically must be increased in order to maintain their effectiveness.

Osbourne ranked mood stabilizers for bipolar disorder, from safest to most worrisome. Lamotrigine is safest. There is no evidence linking it to birth defects, but higher doses are required because of increased clearance during pregnancy. Lithium is next safest. There are cardiac risks for one in 1,200 patients, but these can be monitored. Carbamazepine is third safest. One percent of babies exposed to carbamazepine will develop spina bifida or craniofacial abnormalities. Valproate is least safe during pregnancy. Seven to ten percent of babies exposed to valproate will develop neural tube defects, other malformations, or developmental delay, with a mean decrease of 9 IQ points. The atypical antipsychotics all appear safe so far.

Alternatives and Adjuncts to Medications in Pregnancy

PTSD Increases Risk of Lupus

A new large 2017 study in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatology reports that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in women triples their risk of developing the autoimmune disease lupus. The study included 54,763 civilian women whose health data was tracked over a period of 24 years.

A new large 2017 study in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatology reports that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in women triples their risk of developing the autoimmune disease lupus. The study included 54,763 civilian women whose health data was tracked over a period of 24 years.

Not only did PTSD increase lupus risk, but any traumatic event doubled lupus risk compared to women who were not exposed to trauma.

The researchers, led by Andrea L. Roberts, were taken by surprise at the strong links between trauma and lupus. Trauma was more of a risk factor for lupus than smoking.

Mothers Who Were Abused in Childhood Secrete Less Oxytocin While Breastfeeding

A recent study suggests that women who experienced moderate or severe abuse in childhood secrete less oxytocin while breastfeeding their own children. Oxytocin is a hormone that promotes emotional bonding. The study included 53 women. They breastfed their newborn children while blood samples were collected from the women via IV. Those women with a history of moderate or severe abuse (emotional, physical, or sexual) or neglect (emotional or physical) had lower measures of oxytocin in their blood during breastfeeding than women with no history or abuse in childhood or a history of mild abuse.

A history of abuse or neglect was more common among women with current depression compared to women with a history of depression or anxiety. Women who had never experienced depression or anxiety were least likely to have a history of abuse or neglect.

The study by Alison Steube and colleagues, presented at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, suggests that traumatic events that occur during childhood may have long-lasting effects. These experiences may modulate the secretion of oxytocin in adulthood. Low oxytocin has been linked to depression.

Depression and Obesity Linked in Study of Mexican Americans

A 2015 study by Rene L. Olvera and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry indicated that among 1,768 Mexican-Americans living along the border from 2004–2010, 30% were currently depressed, 14% had severe depression, and 52% were obese. Women were more likely to be depressed, and more likely to have severe depression. Other factors making depression more likely included low education, obesity, low levels of “good” cholesterol, and larger waist circumference. Low education and extreme obesity were also linked to severe depression.

A 2015 study by Rene L. Olvera and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry indicated that among 1,768 Mexican-Americans living along the border from 2004–2010, 30% were currently depressed, 14% had severe depression, and 52% were obese. Women were more likely to be depressed, and more likely to have severe depression. Other factors making depression more likely included low education, obesity, low levels of “good” cholesterol, and larger waist circumference. Low education and extreme obesity were also linked to severe depression.

In a commentary on the article in the same issue, researcher Susan L. McElroy wrote that “the medical field needs to firmly accept that obesity is a risk factor for depression and, conversely, that depression is a risk factor of obesity.” She suggested that people with obesity, those who carry excess weight around their middles, and those who have related metabolic symptoms such as poor cholesterol should all be evaluated for depression. Likewise, those with depression should have their weight and body measures monitored. People with both obesity and depression should be evaluated for disordered eating.

Ratio of Cortisol to CRP May Affect Depression

New research suggests that the ratio of cortisol to C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation, may be a biomarker of depression that affects men and women differently. In women, lower ratios of cortisol to CRP were associated with more severe depression symptoms, including poor quality sleep, sleep disturbances, and decreased extraversion. In men, higher ratios of cortisol to CRP were associated with more daytime disturbance and greater anxiety. The study by E.C. Suarez et al. was published in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.

Further work must be done to confirm whether low cortisol and high inflammation predicts depression in women, while the opposite (high cortisol and low inflammation) predicts depression in men.

Over Half of Russian Women May Be Depressed

In a 2013 article in the journal European Psychiatry, in which researcher Valery V. Gafarov examined depression’s influence on cardiovascular health in Russia, an astonishing 55.2% of women aged 25–64 years in the study were diagnosed with depression. The study, in which 870 women in the city of Novosibirsk were surveyed over 16 years from 1995 to 2010, was part of a World Health Organization program called “MONICA-psychosocial.”

The researchers collected information on the incidence of myocardial infarction (heart attack), arterial hypertension, and stroke among the women. Over the 16 years of the study, 2.2% of the women had heart attacks and 5.1% had strokes. Women with depression were 2.53 times more likely to have a heart attack and 4.63 times more likely to have a stroke than women without depression.

Among women with average education levels, married women with depression were more likely to have heart attacks, hypertension, and strokes. Hypertension was more likely among women who worked as managers or light manual laborers.

Oxytocin for Labor Induction Increases Risk of Bipolar Disorder

Over the past several decades, the practice of giving oxytocin (a hormone that facilitates bonding) to pregnant women to induce labor has become more common, but it comes with several risks to the child. These include increased risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, and cognitive impairment. A new study by Freedman et al. presented at the 2014 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders suggests oxytocin may increase the risk of bipolar disorder as well.

In a sample of 19,000 people, there were 94 cases of bipolar disorder, and birth records revealed that an unexpectedly high number of these cases occurred in people whose mothers had received oxytocin to induce labor, regardless of the duration of the pregnancy. Cognition at ages 3 and 5 was impaired on one measure but not another in those children whose mothers received oxytocin. The researchers concluded that maternal oxytocin to induce labor is a significant risk factor for developing bipolar disorder later in life.

Editor’s Note: Oxytocin appears to take its place among other risk factors for bipolar disorder, which include: prematurity, maternal infection, influenza, the bacterial infection toxoplasmosis, higher insolation (a measure of how powerful radiation from the sun is in a given location), childhood adversity, inflammation (as measured by levels of C-reactive protein), heavy marijuana/THC use, and a family history positive for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or mood disorder, especially bipolar disorder and especially a bilineal history (illness in both parents).

Metformin Effective for Treating Antipsychotic-Induced Amenorrhea, Weight Gain, and Insulin Resistance in Women

Treatment with antipsychotics often has side effects such as amenorrhea (loss of the menstrual period) and weight gain that make sticking to a treatment regimen difficult for some patients. A 2012 study by Wu et al. in the American Journal of Psychiatry suggests that the drug metformin, often used to treat diabetes, can reverse these changes. The 84 female patients recruited for the study were being treated for a first episode schizophrenia, were on one antipsychotic, and had experienced amenorrhea for several months. They received either placebo or 1000mg/day of metformin in addition to their antipsychotic treatment for six months. Seventy-six women completed the trial.

Treatment with antipsychotics often has side effects such as amenorrhea (loss of the menstrual period) and weight gain that make sticking to a treatment regimen difficult for some patients. A 2012 study by Wu et al. in the American Journal of Psychiatry suggests that the drug metformin, often used to treat diabetes, can reverse these changes. The 84 female patients recruited for the study were being treated for a first episode schizophrenia, were on one antipsychotic, and had experienced amenorrhea for several months. They received either placebo or 1000mg/day of metformin in addition to their antipsychotic treatment for six months. Seventy-six women completed the trial.

Metformin was able to reverse the side effects in many of the women. Menstruation returned in 28 of the patients taking metformin compared to only two patients taking placebo. Among those on metformin, body mass index (BMI) decreased by a mean of 0.93, compared to a mean increase in those on placebo (0.85). Insulin resistance improved in the women on metformin as well.

Editor’s Note: Metformin can also delay the onset of type II diabetes in those in the borderline diabetic range. The weight loss on metformin was not spectacular and other options include the combination of the antidepressant bupropion (Wellbutrin) and the opiate antagonist naltrexone (Revia, 50mg/day), monotherapy with topiramate (Topamax), the fixed combination of topiramate and phentermine (Qsymia), or monotherapy with zonisamide (Zonegran).

Female Rodents Are More Sensitive to Defeat Stress and Its Cross-Sensitization to Cocaine

Among rodents, being subjected to defeat stress (when an intruder mouse is threatened by a larger mouse defending its territory) can make an animal more susceptible to cocaine. This is referred to as cross-sensitization.

Among rodents, being subjected to defeat stress (when an intruder mouse is threatened by a larger mouse defending its territory) can make an animal more susceptible to cocaine. This is referred to as cross-sensitization.

Researcher Elizabeth Holly and colleagues have found that compared to males, female rodents are more sensitive to defeat stress and have greater reactions to cocaine and cocaine sensitization following this type of stress. This is probably related to a neuropeptide called corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), which is associated with cross-sensitization. When the mice were exposed to cocaine, there were increases in CRF in a part of the brain called the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which contains cell bodies of dopamine neurons that travel to the nucleus accumbens, the brain’s reward center. Blocking the CRF receptors in the VTA prevented the sensitization to cocaine from occurring in the mice.

Editor’s Note: These data in animals resemble clinical observations in humans that women are more sensitive to stress and are more prone to depression, and can have an exceedingly difficult time stopping cocaine use if they become addicted.

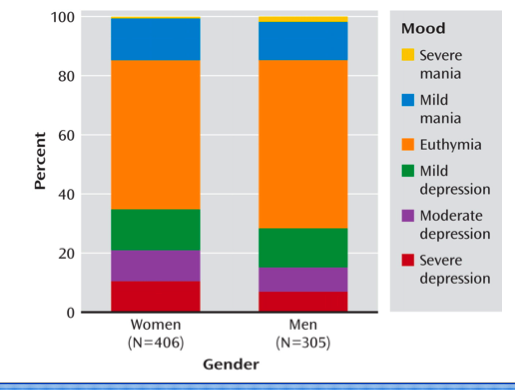

Among Bipolar Patients, Women Spend More Time Depressed Than Men Do

An article by Lori Altshuler et al. (including this editor Robert M. Post) published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2010 presents research that among bipolar patients studied over a period of 7 years, women spent more time than men depressed. Women had higher rates of rapid cycling and of anxiety disorders, both of which were associated to higher rates of depression.