Lithium Reverses Thinning of the Cortex That Occurs in Bipolar Disorder

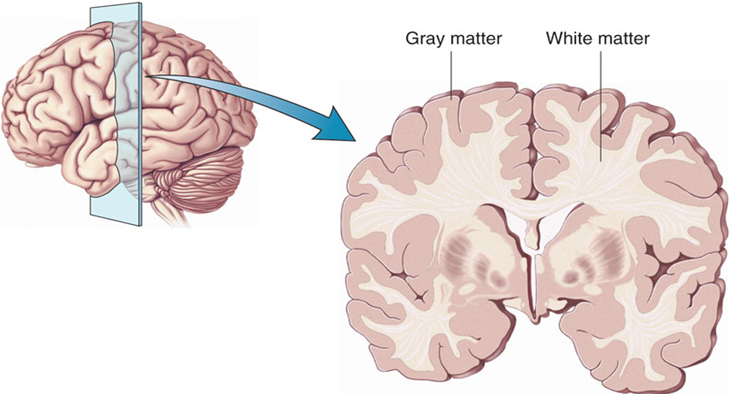

In a 2018 article in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, researcher Derrek P. Hibar reported findings from the largest study to date of cortical gray matter thickness. Researchers in the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group, which comprises 28 international research groups, contributed brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) from 1837 adults with bipolar disorder and 2582 healthy control participants.

Hibar and colleagues in the working group found that in adults with bipolar disorder, cortical gray matter was thinner in the frontal, temporal, and parietal regions of both brain hemispheres. They also found that bipolar disorder had the strongest effect on three regions in the left hemisphere: the pars opercularis, the fusiform gyrus, and the rostral middle frontal cortex.

Those who had had bipolar disorder longer (after accounting for age at the time of the MRI) had less cortical thickness in the frontal, medial parietal, and occipital regions.

A history of psychosis was associated with reduced surface area.

The researchers reported the effects of various drug treatment types on cortical thickness and surface area. In adults and adolescents, lithium was associated with improvements in cortical thickness, and the researchers hypothesized that lithium’s protective effect on gray matter was responsible for this finding. Antipsychotics were associated with decreased cortical thickness.

In people taking anticonvulsant treatments, the thinnest parts of the cortex were the areas responsibly for visual processing. Visual deficits are sometimes reported in people taking anticonvulsive treatments.

Lithium Reverses Some White Matter Abnormalities in Youth with Bipolar Disorder

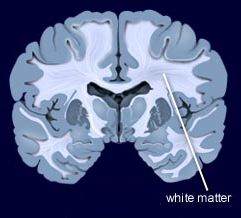

Multiple groups of researchers have reported the presence of white matter tract abnormalities in patients with bipolar disorder. Some of these abnormalities correlate with the degree of cognitive dysfunction in these patients. These white matter tract abnormalities, which are measured with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), are widespread and can appear as early as childhood in people with bipolar disorder. Researcher Vivian Kafantaris mentioned at the 2019 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders that lithium treatment in children and adolescents normalizes these alterations, as described in an article she and her colleagues published in the journal Bipolar Disorders in 2017.

Multiple groups of researchers have reported the presence of white matter tract abnormalities in patients with bipolar disorder. Some of these abnormalities correlate with the degree of cognitive dysfunction in these patients. These white matter tract abnormalities, which are measured with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), are widespread and can appear as early as childhood in people with bipolar disorder. Researcher Vivian Kafantaris mentioned at the 2019 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders that lithium treatment in children and adolescents normalizes these alterations, as described in an article she and her colleagues published in the journal Bipolar Disorders in 2017.

Editor’s Note: This is another reason to consider the use of lithium in children with bipolar disorder. Lithium treatment may help normalize some of the earliest signs of neuropathology in the illness.

Inflammation Associated With Duration of Untreated Unipolar Depression

Researcher Sophia Attwells and colleagues reported at a 2018 scientific meeting that the longer the time that a patient went without treatment for depression, the more inflammation they exhibited on positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Attwells and colleagues used the PET scans to assess the total distribution volume of TSPO, which is a marker of brain microglial activation, a form of inflammation.

Strikingly, in participants who had untreated major depressive disorder for 10 years or longer, TSPO distribution volume was 29–33% greater in the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and insula than in participants who were untreated for 9 years or less. TSPO distribution volume was 31–39% greater in these three important regions of gray matter in participants with long durations of untreated major depressive disorder than in healthy control participants.

Editor’s Note: In schizophrenia, the duration of untreated interval (DUI) is associated with a poor prognosis, but not with inflammation. Researcher Yvette Sheline has also reported that less time on antidepressants compared to more time treated with them was associated with greater hippocampal volume loss with aging in patients with major depression.

Given Attwells and colleagues’ remarkable finding about the adverse effects of the DUI in depression, including inflammation and brain volume loss, and other findings that associate more episodes with poorer functioning, cognition, and treatment responsiveness, physicians and patients should think hard about committing to long-term antidepressant treatment to prevent episodes, beginning early in the course of illness.

This editor (Robert M. Post) would propose that if a second depressive episode occurs after a first depression that responded well to treatment, this would be an appropriate time to start antidepressant prophylaxis. Most guidelines suggest that prophylaxis be started after a third episode, but these recommendations generally do not account for newer data on the pernicious effects of experiencing repeated depressive episodes. In addition to causing dysfunction and disability, going through four depressive episodes doubles the risk of dementia in old age, and this risk increases further with each successive episode, according to researcher Lars Kessing.

Having too many depressions is bad for the brain. In Kessing’s studies, two episodes of unipolar or bipolar depression did not increase the risk of dementia compared to the general population, while four depressions did. One could compare the effects of repeated depressions on the brain to the effects of heart attacks on the heart muscle. A heart might still function well after one or even two heart attacks, but the chances of significant loss of function and the risk of congestive heart failure increase as a function of the number of heart attacks. After even one heart attack, most patients change their lifestyle and/or go on prophylactic medications to reduce risk factors such as elevated blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides, weight, blood sugar, and smoking. The benefits of reducing heart attacks are a no brainer. Trying to prevent recurrent depression with pharmacotherapy and adjunctive psychotherapy after a second depressive episode should be a no brainer too.

In addition, if antidepressants are not effective enough in preventing depressions, lithium is an option, even in unipolar depression, for preventing both episodes and suicide. The evidence of efficacy in both instances is very strong according to an article by Mohammed T. Abou-Saleh in the International Journal of Bipolar Disorders in 2017. The renowned psychiatrist Jules Angst’s recommendation as to when to start lithium treatment was that if a patient had had one episode or more in the previous five years in addition to the present episode, then they were likely to have two further episodes in the following five years, and lithium prophylaxis would be recommended.

White Matter Abnormalities in Obesity

Researcher Ramiro Reckziegel and colleagues reported at a recent scientific meeting that white matter is abnormal in obese adults with bipolar disorder. In a 2018 article in the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin, Reckziegel reported that body mass index (BMI) was associated with reduced fractional anisotropy, a measure of brain fiber integrity, in the cingulate gyrus in patients with bipolar disorder. This finding implies that obesity may play a role in white matter microstructure damage in the limbic system.

White Matter Abnormalities Linked to Irritability in Both Bipolar Disorder and DMDD

At a 2018 scientific meeting, researcher Julia Linke of the National Institute of Mental Health reported that there were white matter tract abnormalities in young people who had irritability associated with either bipolar disorder or disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). Thus, while these two disorders differ in terms of diagnosis, presentation, and family history, they seem to have this neurobiological abnormality in common.

At a 2018 scientific meeting, researcher Julia Linke of the National Institute of Mental Health reported that there were white matter tract abnormalities in young people who had irritability associated with either bipolar disorder or disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). Thus, while these two disorders differ in terms of diagnosis, presentation, and family history, they seem to have this neurobiological abnormality in common.

Brain Scans Differentiate Suicidal from Non-Suicidal Patients with Bipolar Disorder

People with bipolar disorder are at high risk for suicidal behavior beginning in adolescence and young adulthood. A 2017 study by Jennifer A. Y. Johnston and colleagues in the American Journal of Psychiatry uses several brain-scanning techniques to identify neurobiological features associated with suicidal behavior in people with bipolar disorder compared to people with bipolar disorder who have never attempted suicide. Clarifying which neural systems are involved in suicidal behavior may allow for better prevention efforts.

People with bipolar disorder are at high risk for suicidal behavior beginning in adolescence and young adulthood. A 2017 study by Jennifer A. Y. Johnston and colleagues in the American Journal of Psychiatry uses several brain-scanning techniques to identify neurobiological features associated with suicidal behavior in people with bipolar disorder compared to people with bipolar disorder who have never attempted suicide. Clarifying which neural systems are involved in suicidal behavior may allow for better prevention efforts.

The study included 26 participants who had attempted suicide and 42 who had not. Johnston and colleagues used structural, diffusion tensor, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques to identify differences in the brains of attempters and non-attempters.

Compared to those who had never attempted suicide, those who had exhibited reductions in gray matter volume in the orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum. They also had reduced white matter integrity in the uncinate fasciculus, ventral frontal, and right cerebellum regions. In addition, attempters had reduced functional connectivity between the amygdala and the left ventral and right rostral prefrontal cortex. Better right rostral prefrontal connectivity was associated with less suicidal ideation, while better connectivity of the left ventral prefrontal area was linked to less lethal suicide attempts.

Breathing in Through the Nose Enhances Judgment and Memory

A 2016 study published in the Journal of Neuroscience reported that the rhythm of breathing changes electrical activity in the brain and can improve emotional judgments and recall. Breathing in through the nose seemed to produce benefits compared to breathing out or to breathing in through the mouth.

Participants more easily identified a fearful face if they viewed it while breathing in. They also had an easier time remembering objects they observed while breathing in. The effects were not seen if the participants breathed through their mouth.

The researchers, led by Christina Zelano, reported that there was a major difference in brain activity in the amygdala and hippocampus during inhalation versus exhalation. Breathing in, in addition to stimulating the olfactory cortex responsible for smell perception, seems to activate the entire limbic system, the emotional center of the brain.

Brain Inflammation Found in Autopsy Studies of Teen and Adult Suicides

Suicide and depression have both been linked to elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid. A recent study finds that these inflammatory markers are also elevated in the brains of teens and depressed adults who died from suicide.

In autopsy studies, researcher Ghanshyam N. Pandey measured levels of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1beta, interleukin 6, and TNF-alpha in the brains of teen suicide victims, and compared these to the brains of teens who died from other causes. Pandey also measured levels of interleukin-1beta, interleukin 6, interleukin 8, interleukin 10, interleukin 13, and TNF-alpha in the prefrontal cortex of depressed adult suicide victims and compared them to levels in adults who died of other causes.

There were abnormalities in the inflammatory markers in the brains of those who died from suicide compared to their matched controls. The suicide victims had higher levels of interleukin-1beta, interleukin 6, and TNF-alpha than the controls. Among the adults, levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 were low in the suicide victims while levels of Toll-like receptors (TLR3 and TLR4), which are involved in immune mechanisms, were high.

Brain inflammation has also been observed in positron emission tomography (PET) scans of depressed patients, where signs of microglial activation can be observed. Elevated inflammatory cytokines are also found in the blood of some people with bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia.

Pandey presented this research at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Improves Depression, PTSD by Improving Brain Connectivity

A recent study clarified how cognitive behavioral therapy improves symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The participants were 62 adult women. One group had depression, one had PTSD, and the third was made up of healthy volunteers. None were taking medication at the time of the study. The researchers, led by Yvette Shelive, used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to analyze participants’ amygdala connectivity.

At the start of the study, participants with depression or PTSD showed diminished connectivity between the amygdala and brain areas related to cognitive control, the process by which the brain can vary behavior and how it processes information in the moment based on current goals. The lack of connectivity reflected the severity of the participants’ depression. Twelve weeks of cognitive behavioral therapy improved mood and connectivity between the amygdala and these control regions, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the inferior frontal cortex. These regions also allow for executive functioning, which includes planning, implementation, and focus.

Some Evidence of Brain Inflammation in Depression

Many studies have found links between levels of inflammatory molecules in the blood and depression or depressive symptoms. There has been less research about inflammation in the brain and its possible role in depressive illness. Improvements in positron emission topography (PET) scan technology now allow for better brain imaging that can reveal when microglia are activated. (Microglia serve as the main immune responders in the central nervous system.)

Many studies have found links between levels of inflammatory molecules in the blood and depression or depressive symptoms. There has been less research about inflammation in the brain and its possible role in depressive illness. Improvements in positron emission topography (PET) scan technology now allow for better brain imaging that can reveal when microglia are activated. (Microglia serve as the main immune responders in the central nervous system.)

A study by researcher Jeffrey Meyer found evidence of microglial activation in several brain regions (including the prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the insula) in people in an episode of depression who were not receiving any treatments. Participants with more microglial activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and insula had more severe depression and lower body mass indexes.

Meyer, who presented this research at a scientific meeting in December, called it strong evidence for brain inflammation in depressive episodes, and suggested that treatments that target microglial activation would be promising for depression.

However, at the same meeting, researcher Erica Richards reported that she had not been able to replicate Meyer’s results. Her research, which included depressed participants both on and off medication and non-depressed participants, found that depressed participants did show more inflammation in the two brain regions she targeted, the anterior cingulate and the subgenual cortices, but this difference did not reach statistical significance, particularly when patients taking antidepressants were included in the calculations. Richards hopes that with a greater sample size, the data may show a significant difference in brain inflammation between depressed and non-depressed participants.