Long-term Course of Bipolar Illness is Most Difficult

While the 4 major childhood-onset psychiatric illnesses we discussed this week (bipolar, unipolar, ADHD, and anxiety disorders) show long term difficulties into adulthood in the majority of instances, it appears that the most severely impacted are those with bipolar disorder. These data are also consistent with retrospective data from multiple cohorts of adults with bipolar disorder, which indicate that those whose illness began in childhood fared more poorly in adulthood than those with adult-onset illness. Thus, while there has been a modicum of treatment research in childhood depression and anxiety disorder and a plethora of treatment studies in ADHD, the dearth of treatment studies in children with bipolar disorder is all the more disconcerting.

Bipolar disorder is common, occurring in some 2 to 3% of children and adolescents, and carries a relatively grave prognosis into adulthood in the majority of instances, especially when it is inadequately treated. Virtually all of the investigators in the area of childhood-onset bipolar who presented at the AACAP meeting have pleaded for increased treatment research for bipolar disorder in children, and one can only hope that their message is soon heard.

Long-term Outcomes for Childhood-Onset Disorders: Anxiety Disorders

A symposium at the 2012 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) examined long-term outcomes of childhood onset disorders, including bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, ADHD, and anxiety disorder.

Course of Childhood Onset Anxiety Disorders

Danny Pine presented a study of 191 adolescents with an anxiety disorder, among whom 36% showed no anxiety disorder in adulthood, while 62% continued to have an anxiety disorder. Among a control population, 390 adolescents without an anxiety disorder remained so in adulthood, while 36 developed new onset of an anxiety disorder in adulthood. Sixty-two of the 98 participants who had anxiety disorders in adulthood had had the disorder continuously from its onset in adolescence. Thus, it appears that approximately two-thirds of adults with an anxiety disorder show a persistence of their childhood onset anxiety disorder, while approximately 1/3 had a new anxiety disorder diagnosis.

Editor’s Note: While all 4 of these major childhood onset psychiatric illnesses (bipolar, unipolar, ADHD, and anxiety disorders) show long term difficulties into adulthood in the majority of instances, it appears that the most severely impacted are those with bipolar disorder. These data are also consistent with retrospective data from multiple cohorts of adults with bipolar disorder, which indicate that those whose illness began in childhood fared more poorly in adulthood than those with adult-onset illness. Thus, while there has been a modicum of treatment research in childhood depression and anxiety disorder and a plethora of treatment studies in ADHD, the dearth of treatment studies in children with bipolar disorder is all the more disconcerting.

Bipolar disorder is common, occurring in some 2 to 3% of children and adolescents, and carries a relatively grave prognosis into adulthood in the majority of instances, especially when it is inadequately treated. Virtually all of the investigators in the area of childhood-onset bipolar who presented at the AACAP meeting have pleaded for increased treatment research for bipolar disorder in children, and one can only hope that their message is soon heard.

Long-term Outcomes for Childhood-Onset Disorders: ADHD

A symposium at the 2012 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) examined long-term outcomes of childhood onset disorders, including bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, ADHD, and anxiety disorder.

Course of Childhood Onset ADHD

Lily Hechtman reported on the long-term difficulties of adolescents who had childhood onset of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). They often experienced: continued typical symptoms including restlessness and over-activity, decreased academic performance, deficits in social interactions, and decreased self-esteem.

Twenty-five percent developed an antisocial personality disorder with 19-50% of these having difficulties with the legal system. There were again three distinct groups that showed different patterns of outcome. Thirty percent of the sample showed essential normality into adolescence and young adulthood. Sixty percent had continuous ADHD symptomatology, and 10% had serious psychiatric illness resulting in jail or hospitalization.

Other follow-up studies that extend as far as 40 years suggest that ADHD persists in older adults at a rate of 36%, while antisocial personality persists in 10%, and substance abuse in 17%. Adolescent controls went on to experience these disorders in adulthood at respective rates of 13%, 0%, and 7%. Hechtman provided systematic data that treatment of ADHD was not a risk factor for the subsequent adoption of substance abuse.

In another study, a latent class analysis showed that about 52% of those with ADHD became well and stayed well. The predictors of this good outcome were: lack of maternal drug exposure in the prenatal period, a stable family, not being on welfare, not having a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, not having a severe form of ADHD, and not having lower social functioning at baseline.

There is some evidence that treatment of ADHD in young adults can lead to psychosocial benefits. In one study performed in 1984, a group of college-age participants treated with stimulants for 3 to 5 years showed improvement in social skills and self-esteem, but surprisingly, no increase in academic performance.

Course of Childhood Onset Anxiety Disorders

Danny Pine presented a study of 191 adolescents with an anxiety disorder, among whom 36% showed no anxiety disorder in adulthood, while 62% continued to have an anxiety disorder. Among a control population, 390 adolescents without an anxiety disorder remained so in adulthood, while 36 developed new onset of an anxiety disorder in adulthood. Sixty-two of the 98 participants who had anxiety disorders in adulthood had had the disorder continuously from its onset in adolescence. Thus, it appears that approximately two-thirds of adults with an anxiety disorder show a persistence of their childhood onset anxiety disorder, while approximately 1/3 had a new anxiety disorder diagnosis.

Long-term Outcomes for Childhood-Onset Disorders: Depression

A symposium at the 2012 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) examined long-term outcomes of childhood onset disorders, including bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, ADHD, and anxiety disorder.

The Course of Childhood Onset Depression

Gabrielle Carlson presented the work of Karen Wagner on unipolar depression, in which there was a 15.3% incidence of unipolar depression in female adolescents, and 7.7% incidence in males. The overall incidence increased with age; from 8.4% in children aged 13, to 12.6% in children age 15 and 21.4% in children age 17. Average duration of a depressive episode was 17 months. While 85% recovered, 40% of those who recovered experienced a recurrence.

Carlson also presented data from Barbara Geller indicating that among children hospitalized with pre-pubertal onset of depression, 33% eventually were diagnosed with bipolar I disorder. If diagnoses of bipolar II and BP-NOS were included, the rate at which these children who got depressed before puberty eventually developing a bipolar disorder increased to an astonishingly high 49%. Thus, very early onset depression has a 50/50 chance of predicting an eventual bipolar disorder diagnosis.

Predictors of a more difficult course of depressive illness presentation were: earliest onset, more than 3 episodes, longer duration of depressive illness, and a positive family history. Those with early-onset depression had more suicidality, smoking, drug abuse, alcoholism, and an increased incidence of not having children when they became adults.

The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) performed at the National Institute of Mental Health compared antidepressant response to fluoxetine, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), or the combination of fluoxetine plus CBT. Early in the study, the combination was most effective, with response in 39% of the children, compared to 24% for fluoxetine and 19% for CBT alone. However, after 3 years of follow up, all of the groups showed a relatively similar percent response: 60% for the combination; 55% for fluoxetine; and 64% for CBT.

Long-term Outcomes for Childhood-Onset Disorders: Bipolar Disorder

This week we’ll be summarizing the research on long-term outcomes for four childhood-onset illnesses: bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anxiety disorder. The information comes from a symposium at the 2012 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP).

Course of Childhood Onset Bipolar Disorder

At the AACAP meeting, researcher Boris Birmaher discussed the considerable differences in presentations of bipolar disorder in childhood versus in adolescence. In childhood there appeared to be a more sub-syndromal symptoms or diagnoses of bipolar not otherwise specified (BP-NOS). There were more mixed symptoms, more hallucinations, worse course of illness, more comorbidities with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, and more separation anxiety disorder. In contrast, in adolescence there were more diagnoses of bipolar I and bipolar II, major depression, mania with elation and grandiosity, substance abuse, and conduct disorder.

Birmaher reported that while most children with early-onset mania recovered within two years, roughly 80% experienced recurrences over the next two to five years. Over a follow-up period of four years, 30% remained euthymic, 40% had continuing substantial symptoms, and 20% remained seriously ill. Birmaher’s data indicate that those with childhood-onset bipolar illness remained symptomatic during 60% of the follow-up period.

Predictors of a more difficult outcome included an early onset, a BP-NOS presentation, longer duration of illness, any comorbid illness, lower socioeconomic status, and a family history of bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives. Birmaher reported that these data in childhood-onset mania were consistent with earlier research by Judd and colleagues in a longitudinal follow-up study of adult patients with bipolar disorder. However, there were three major differences. The proportion of time well was lower in children (41.1%) than in adults (52.7%). Time in mixed episodes or rapid cycling was higher in childhood-onset bipolar disorder (28.9%) than in adults (5.9%). Rapid changes in polarity were also more common in children (15.7% ) than in adults (3.5%). Read more

Anxiety and Depressive Disorders Often Precede the Onset of Bipolar Disorder in Those At High Risk Due to Family History

At the 2012 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) meeting, Anne Duffy and Gabrielle A. Carlson sponsored a symposium on the association between anxiety and minor mood disorders and subsequent bipolar disorder in those at high risk. Researchers presenting at the symposium consistently found that there is a sequence in which young people at high risk for bipolar disorder develop increasingly severe illnesses: first anxiety, then mood disorders, then bipolar illness.

One difference: the incidence of childhood-onset bipolar disorders in those at high risk because a parent has the disorder was lower in Canada, Switzerland, and the Netherlands than it was in the US.

Duffy, a professor of psychiatry in Calgary, noted that bipolar disorder is highly heritable even though most adults with bipolar illness do not have a family history of bipolar illness among their first-degree relatives. She shared estimates that if one parent has bipolar disorder their offspring have a 5% lifetime risk of developing bipolar disorder. If both parents have bipolar disorder their offspring have a 25% risk of developing bipolar disorder and a 35% incidence of developing any affective disorder (although other data by Lapalme et al. suggest it may be as high as 60%).

Duffy found that when parents responded well to lithium, their children tended to do the same. Lithium-responsive patients tended to be those without anxiety disorder and substance abuse and who had classic bipolar episodes and clear well intervals between episodes. Read more

It Appears Antidepressants and Stimulants Do Not Hasten the Onset of Bipolar Disorder in Children

It is a common clinical assumption that early treatment of depression with antidepressants may be a risk factor for hastening the onset of subsequent bipolar disorder. Accumulating evidence indicates that this may not be the case. At a symposium at the 2012 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) researchers in the field shared the latest findings on antidepressant-induced manic symptoms in youth (AIMS), and there was a surprising consensus that antidepressants do not increase the risk of subsequent bipolar disorder onset when used for the treatment of childhood-onset depression.

Symposium speakers Kiki Chang, Melissa P. DelBello, and David Axelson all agreed that antidepressant treatment was not a risk factor for bipolar disorder.

DelBello shared data from a study in which antidepressant treatment was associated with a lower likelihood of mania during follow-up. Antidepressants were typically discontinued if the patient switched into manic-like symptoms or increased irritability or aggression. These symptoms tended to occur in children who were younger, who had a smaller volume of the amygdala, and in those who had a positive family history for bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives.

Axelson indicated that his data represented only a “bird’s-eye view,” but suggested that antidepressants do not cause or hasten the onset of bipolar disorder when used for treating depression in children. He also reported results from a naturalistic study in which stimulants also did not increase the risk of subsequent bipolarity.

Several of the presenters discussed how they would treat children with an early-onset depression when there is a family history of bipolar disorder. Read more

Long Delays to First Treatment Are Crippling Many with Bipolar Disorder: What You Can Do

An article published by N. Drancourt et al. in the journal Acta Psychiatra Scandinavica this year examined the duration of the period between a first mood episode and treatment with a mood stabilizer among 501 patients with bipolar disorder. The time between a first episode of depression, mania, or hypomania and first treatment averaged 9.7 years. The authors conclude that more screening, better recognition of the early stages of the illness, and greater awareness are needed to decrease this long delay.

Editor’s Note: The article by Dancourt et al. replicates earlier findings of an average treatment delay of 10 years among bipolar patients from the treatment network in which this editor (Robert Post) is an investigator (formerly the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network, now called the Bipolar Collaborative Network). The duration of the untreated interval (DUP) for patients with bipolar disorder is unacceptably long and carries a heavy price.

Those with the earliest age of onset experience the longest delay to first treatment. Early onset is associated with poor outcome compared to adult onset bipolar disorder, and the duration of time untreated adds a separate, independent risk of a worse outcome in adulthood, especially more frequent and severe depression, more episodes, and less time well.

What patients and doctors can do to shorten this interval to first treatment: Know the risk factors for early onset bipolar disorder so you can seek evaluation and advise treatment as appropriate. Read more

Risks and Difficulties of Treating Childhood-Onset Bipolar Disorder

Early treatment is needed in childhood onset bipolar disorder

Early treatment is needed in childhood onset bipolar disorder

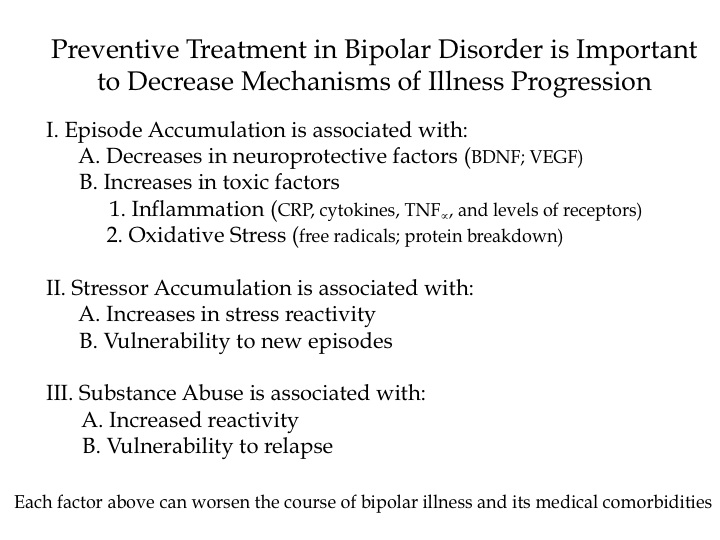

Multiple factors make childhood-onset bipolar disorder a difficult problem for affected children and families. Early onset is common, and treatment is often delayed or inappropriate. It takes an average of nine months to achieve remission, and relapses are common. In studies children have remained symptomatic for an average of two-thirds of the time they receive naturalistic follow up treatment, and the illness impairs social and educational development. Episodes and stressors tend to accumulate, and substance abuse is a frequent complication. Dysfunction and disability occur at a high rate among children with the illness, and suicidal ideation and acts are common.

When we surveyed adults in our treatment network, the Bipolar Collaborative Network (BCN), about the history of their illness, we found that the duration of the time lag between illness onset and first treatment was independently related to a poor outcome in adulthood. A longer delay to first treatment was associated in adulthood with greater depression severity, more days depressed, fewer days euthymic, more episodes, and more ultradian cycling (or cycling within a single day). Because treatment delay is a risk factor that can be avoided or prevented, efforts should be made to initiate treatment early in the course of bipolar illness. Read more