Antidepressants and Ketamine Induce Resilience in Animals Susceptible to Depression-Like Behavior

To study depression in humans, researchers look to rodents to learn more about behavior. Rodents who are repeatedly defeated by more aggressive animals often begin to exhibit behavior that resembles depression. At the 2014 meeting of the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP), researcher Andre Der-Avakian reported that in a recent study, repeated experiences of social defeat led to depressive behavior in a subgroup of animals (which he calls susceptible), but not in others (which he calls resilient). Among many biological differences, the resilient animals showed increases in neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus.

To study depression in humans, researchers look to rodents to learn more about behavior. Rodents who are repeatedly defeated by more aggressive animals often begin to exhibit behavior that resembles depression. At the 2014 meeting of the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP), researcher Andre Der-Avakian reported that in a recent study, repeated experiences of social defeat led to depressive behavior in a subgroup of animals (which he calls susceptible), but not in others (which he calls resilient). Among many biological differences, the resilient animals showed increases in neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus.

Chronic treatment of the susceptible animals with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant fluoxetine or the tricyclic antidepressant desipramine, which both increase neurogenesis, also reversed the depressive behavior in about half of the animals. A single injection of the anesthetic ketamine (which has rapid-acting antidepressant effects in humans) reversed social avoidance behavior in about 25% of the animals. One depression-like symptom was anhedonia (loss of pleasure from previously enjoyed activities), which researchers measured by observing to what extent the animals engaged in intracranial self-stimulation, pressing a bar to stimulate the brain pleasurably. The effectiveness of the drugs in inducing resilient behavior was related to the degree of anhedonia seen in the animals. The drugs worked less well in the more anhedonic animals (those who gave up the intracranial stimulation more easily, indicating that they experienced less reward from it.)

Ketamine for Chronic PTSD

We reported in BNN Volume 17, Issue 6 in 2013 on researchers’ efforts to treat symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder using the drug ketamine. This research by Adriana Feder et al. has now been published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

In the study of 41 patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, patients showed a greater reduction in symptoms 24 hours after receiving intravenous (IV) ketamine than after taking IV midazolam, a benzodiazepine used as an active placebo control because it produces anti-anxiety and sedating effects similar to ketamine’s. The patients ranged in age from 18 to 55 years of age and were free of other medication for two weeks before the study. Ketamine was also associated with reduction in depressive symptoms and with general clinical improvement, and side effects were minimal.

IV Ketamine Produces Antidepressant Effects More Rapidly Than ECT

More and more evidence suggests that drugs such as ketamine that work by blocking the brain’s NMDA receptors can produce rapid-acting antidepressant effects in patients with depression.

More and more evidence suggests that drugs such as ketamine that work by blocking the brain’s NMDA receptors can produce rapid-acting antidepressant effects in patients with depression.

In a recent study by Ghasemi et al. published in the journal Psychiatric Research, 18 patients with unipolar depression were divided into two groups, one that received intravenous infusions of ketamine hydrochloride (0.5 mg/kg over 45 minutes) three times (every 48 hours), and another that received electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) on the same schedule.

Ketamine produced antidepressant effects more quickly than ECT, and these effects were significantly better than baseline for the duration of the study, but not significantly different from those achieved through ECT by the end of the study.

Editors Note: These data continue to add to the already strong findings that ketamine produces rapid-onset antidepressant effects. When and where ketamine should be incorporated into routine clinical treatment of depression remains to be further clarified.

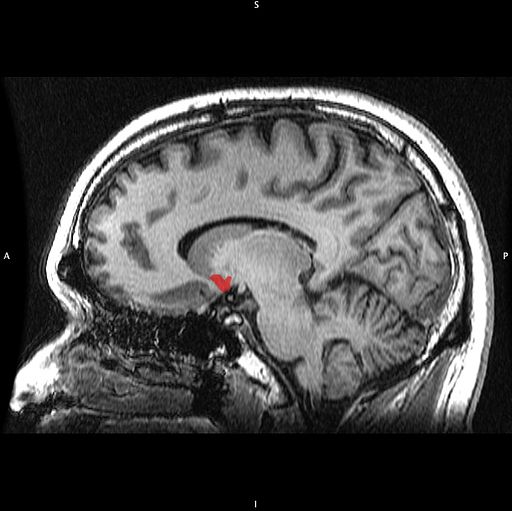

The Nucleus Accumbens in Depression

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) keeps neurons healthy and is critical for long-term memory and synapse formation. BDNF levels increase in the nucleus accumbens (the brain’s reward center) and decrease in the hippocampus during clinical depression and chronic cocaine use. In rodents, the same changes in BDNF levels occur during defeat stress (which resembles human depression).

Rodents who are repeatedly defeated by a larger rodent exhibit behaviors such as social withdrawal, lethargy, and decreased interest in sucrose. The increases in BDNF in the nucleus accumbens of these rodents could reflect the learning that takes place during the repeated defeat stress and the depression-like behaviors that follow it. Blocking the BDNF increases in the nucleus accumbens prevents these behaviors from developing.

Chadi Abdallah and other researchers at Yale University recently found that the left nucleus accumbens of patients with treatment-resistant depression is enlarged compared to normal controls, and the drug ketamine, which produces rapid-onset antidepressant effects, rapidly decreases the volume of the nucleus accumbens in the depressed patients. The mechanism by which it does so is unknown, but could reflect some suppression of the depressive learning.

Any relationship between the volume of the nucleus accumbens and its levels of BDNF is unknown, but ketamine’s effect on the size of this brain region could be linked to a decrease in the defeat-stress memories.

A Common Variant of BDNF Predicts Non-Response to IV Ketamine

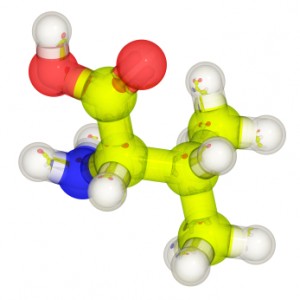

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a protein in the brain that protects neurons and is necessary for long-term memory and learning. Different people have different genetic variations in BDNF depending on which amino acid the gene that codes for it inserts into the protein, valine or methionine. There are three possible combinations that vary in their efficiency. The Val66Val allele of BDNF is the most efficient for secreting and transporting BDNF within the cell body to synapses on dendrites, and is also a risk factor for early onset of bipolar disorder and rapid cycling. Twenty-five percent of the population has a Met variant (either Val66Met or Met66Met), which functions less efficiently. These people have mild decrements in some cognitive processing.

Increases in BDNF are necessary to the antidepressant effects of intravenous ketamine. In animals, ketamine also rapidly changes returns dendritic spines that had atrophied back to their healthy mushroom shape in association with its antidepressant effects. According to research published by Gonzalo Laje and colleagues in the journal Biological Psychiatry in 2012, depressed patients with the better functioning Val66Val allele of BDNF respond best to ketamine, while those with the intermediate functioning Val66Met allele respond less well.

Researcher Ronald S. Duman of Yale University recently found that increases in BDNF in the medial prefrontal cortex are necessary to the antidepressant effects of ketamine. If antibodies to BDNF (which block its effects) are administered to the prefrontal cortex, antidepressant response to ketamine is not observed.

Duman also found that calcium influx through voltage sensitive L-type calcium channels is necessary for ketamine’s antidepressant effects. A genetic variation in CACNA1C, a gene that codes for a subunit of the dihydropiridine L-type calcium channel, is a well-replicated risk factor for bipolar disorder. One might predict that those patients with the CACNA1C risk allele, which allows more calcium influx into cells, would respond well to ketamine.

Rationale for Using Ketamine in Youth with Treatment-Resistant Depression

At the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Vilma Gabbay of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine reiterated the findings from the TORDIA (Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents) study that 20% of young people with depression remained resistant to treatment, childhood-onset depression was more likely to be recurrent and more difficult than adult-onset depression in the long run, and suicide was the second leading cause of death in 12- to 17-year-olds in 2010 according to a Centers for Disease Control report in May 2013. Anhedonia (a loss of pleasure in activities once enjoyed) was the most difficult symptom to treat in adolescents.

Gabbay carefully explained some of the rationales for using ketamine in young people with depression. The presence of inflammation is a poor prognosis factor, and ketamine has anti-inflammatory effects, decreasing levels of inflammatory markers CRP, TNF-alpha, and Il-6.Given that ketamine has been widely used as an anesthetic for surgical procedures, its safety in children has already been demonstrated. Ketamine did not appear to cause behavioral sensitization (that is, increased effect upon repetition) in a report by Cho et al. in 2005 that included 295 patients.

As noted previously, Papolos et al. reported in a 2012 article in the Journal of Affective Disorders that intranasal ketamine at doses of 50 to 120 mg was well-tolerated and had positive clinical effects in 6- to 19-year-olds with the fear of harm subtype of bipolar disorder that had been highly resistant to treatment with more conventional drugs.

Gabbay reluctantly endorsed further cautious controlled trials in children and adolescents, in light of ketamine’s suggested efficacy and good safety profile, which stands in contrast to its popular reputation as a party drug or “Special K.”

Editor’s Note: The discussant of the symposium, Neal Ryan of Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, added an exquisitely brief discussion suggesting that ketamine should ultimately be studied in combination with behavioral and psychotherapeutic procedures to see if its therapeutic effects could be enhanced. He made this suggestion based on the data that ketamine has important synaptic effects, increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is important for healthy cells and long-term memory, and reverting thin dendritic spines caused by stress back to their normal mushroom shape. This editor (Robert Post) could not be more in agreement.

IV Ketamine Superior to IV Midazolam in Adults with PTSD

In a recent study, ketamine performed better than an active comparator on several measures in adults with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Since ketamine has noticeable dissociative effects, researchers have looked for another drug with mind-altering effects that would be a more appropriate comparator than placebo.

At the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Adriana Feder of Mount Sinai Hospital reported on the randomized study in those with PTSD, in which intravenous ketamine was compared to intravenous midazolam, a potent benzodiazepine that produces anti-anxiety and sedating effects. Murrough et al. previously showed that intravenous ketamine was superior to midazolam in treatment-resistant depression.

In the randomized study Feder described, the participants had suffered PTSD from a physical or sexual assault and had been ill for 12 to 14 years. Those who received ketamine improved more, in some instances for as long as two weeks (ketamine’s blood levels disappear after a few hours, and its clinical antidepressant effects usually last only a few days). Reports of side effects included three patients with blood pressure increases requiring treatment with propranolol, and four patients who each had a transient episode of vomiting.

These controlled data parallel previous open observations. When ketamine was used as a surgical anesthetic during operations on burn patients, only 26.9% subsequently reported PTSD compared to 46.4% who developed PTSD when an alternative to ketamine was used as the anesthetic.

Intranasal Ketamine May Be an Alternative to IV in Refractory Depression

At the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kyle Lapidus of Mount Sinai Hospital reviewed the literature from controlled studies on the efficacy of intravenous (IV) ketamine at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg over a 40-minute infusion for adults with treatment-resistant depression (with consistent response rates of 50% or more), and suggested that intranasal ketamine may also be effective.

Ketamine is a strong blocker of the glutamate NMDA receptor. At high doses (6 to 12 mg/kg) it is an anesthetic, at slightly lower doses (3 to 4 mg/kg) it is psychotomimetic (causing psychotic symptoms) and is sometimes used as a drug of abuse, and at very low doses it is a rapidly acting antidepressant, often bringing about results within 2 hours. Antidepressant effects typically last 3 to 5 days, so the question of how to sustain these effects is a major one for the field.

Murrough et al. reported in Biological Psychiatry in 2012 that five subsequent infusions of ketamine sustained the initial antidepressant response and appeared to be well tolerated by the patients. Another NMDA antagonist, riluzole (used for the treatment of ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease), did not sustain the acute effects of ketamine, and now lithium is being studied as a possible strategy for doing so.

The bioavailability of ketamine in the body depends on the way it is administered. Compared to IV administration, intramuscular (IM) administration is painful but results in 93% of the bioavailability of IV ketamine. Intranasal (IN) administration results in 25-50% of the bioavailability of IV administration, while oral administration results in only 16-20% of the bioavailability of IV administration, so Lapidus chose to study the IN route. He compared intranasal ketamine at doses of 50mg (administered in a mist ) to 0.5 ml of intranasal saline. Both were given in two infusions seven days apart. Lapidus observed good antidepressant effects and good tolerability. Papolos et al. had reported earlier that intranasal ketamine had good effects in a small open trial in treatment-resistant childhood onset bipolar disorder.

Editor’s Note: Further studies of the efficacy and tolerability of intranasal ketamine are eagerly awaited.

New Research on Ketamine

The drug ketamine can produce antidepressant effects within hours when administered intravenously.

The drug ketamine can produce antidepressant effects within hours when administered intravenously.

Finding an Appropriate Control

Comparing ketamine to placebo has challenges because ketamine produces mild dissociative effects (such as a feeling of distance from reality) that are noticeable to patients. At the 2013 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, James W. Murrough and collaborators at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine reported their findings from the first controlled trial of intravenous ketamine in depression that uses an active control, the short-acting benzodiazepine midazolam, which has sedative effects and decreases anxiety, but is not known as an antidepressant. On virtually all measures intravenous ketamine was a more effective antidepressant following 2 infusions per week.

These data help dispel one of the criticisms of intravenous ketamine, that studies of the drug have not been sufficiently blinded (when patients and medical staff are kept from knowing which patients receive an active treatment and which are in the placebo control group) and that the lack of an appropriate active placebo contributed to the dramatic findings about ketamine’s antidepressant effects. It now appears that these criticisms have been appropriately answered and that intravenous ketamine is highly effective not only in comparison to placebo but also to an active comparator.

This research was presented as a poster at the meeting and published as abstract #442 in the meeting supplement to the journal Biological Psychiatry, Volume 73, Number 9S, and was also published in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 2013.

Slowing Down Ketamine Infusions to Reduce Side Effects

Ketamine is commonly given in 40-minute intravenous infusions. Timothy Lineberry from the Mayo Clinic reported in Abstract #313 from the meeting that slower infusions of ketamine over 100 minutes were also effective in producing antidepressant effects in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Lineberry’s research group used the slower infusion in order to increase safety and decrease side effects, such as the dissociative effects discussed above. In the 10 patients the group studied, they observed a response rate of 80% and a remission rate of 50% (similar to ketamine’s effects with 40-minute infusions).

Family or Personal History of Alcohol Dependence Predicts Positive Response to Ketamine in Depression

Mark J. Niciu and collaborators at the NIMH reported in Abstract #326 that a personal or family history of alcohol dependence predicted a positive response to IV ketamine in patients with unipolar depression.

Ketamine Acts on Monoamines in Addition to Glutamate

Ketamine’s primary action in the nervous system is to block glutamate NMDA receptors in the brain. In addition to its effects on glutamate, it may also affect the monoamines norepinephrine and dopamine. Kareem S. El Iskandarani et al. reported in Abstract #333 that in a study of rats, ketamine increased the firing rate of norepinephrine neurons in a part of the brain called the locus coeruleus and also increased the number of spontaneous firing dopamine cells in the ventral tegmental area of the brain.

Editor’s Note: These data showing that ketamine increased the activity of two monoamines could help explain ketamine’s ability to induce rapid onset of antidepressant effects, in addition to its ability to immediately increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, important for long-term memory and the creation of new synapses) and to restore healthy mushroom-shaped spines on the dendrites of neurons in the prefrontal cortex.

Family History Of Alcoholism Predicts Positive Response To Ketamine

The drug ketamine can bring about antidepressant effects rapidly when given intravenously, but these effects last only a few days. In a recent study, bipolar depressed patients with alcoholism or a family history of alcoholism in first-degree relatives had a more extended positive antidepressant response to IV ketamine than those without this history, and fewer adverse effects from the treatment. The study, published by David Luckenbaugh et al. from the National Institute of Mental Health in the journal Bipolar Disorders in December 2012, replicates similar findings in patients with unipolar depression, where positive family history of alcoholism also predicted better response and fewer adverse effects from IV ketamine.

The drug ketamine can bring about antidepressant effects rapidly when given intravenously, but these effects last only a few days. In a recent study, bipolar depressed patients with alcoholism or a family history of alcoholism in first-degree relatives had a more extended positive antidepressant response to IV ketamine than those without this history, and fewer adverse effects from the treatment. The study, published by David Luckenbaugh et al. from the National Institute of Mental Health in the journal Bipolar Disorders in December 2012, replicates similar findings in patients with unipolar depression, where positive family history of alcoholism also predicted better response and fewer adverse effects from IV ketamine.

Alcohol and ketamine have a common mechanism of action. They are both antagonists of the glutamate NMDA receptor, meaning they limit the effects of glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. This suggests a theoretical explanation for why a history of alcoholism might relate to ketamine response.

Editor’s Note: Family history appears to be linked to how patients respond to different mood stabilizers. Lithium works best in those patients with a positive family history of mood disorders (especially bipolar disorder). Carbamazepine works best in those without a family history of bipolar disorder among first-degree relatives. Lamotrigine works best in those with a positive family history of anxiety disorders or alcoholism.

Drugs that are effective in patients with a family history of alcoholism all target glutamate in the brain. Lamotrigine decreases glutamate release, while ketamine reduces glutamate’s effects at the receptor. Both decrease glutamate function or activity. Like lamotrigine, carbamazepine also decreases glutamate release and has good effects in those with a history of alcoholism.

Memantine is another mood-stabilizing drug that is an antagonist of the NMDA receptor, like ketamine and alcohol. It will be interesting to see whether memantine will also be successful in those with a personal or family history of alcoholism.