Treating Substance Abuse: A Step Forward

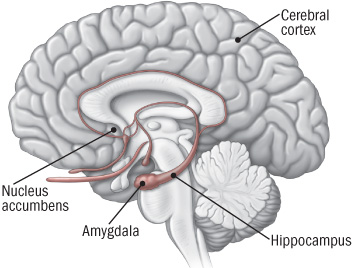

New discoveries in neuroanatomy are helping clarify what addiction looks like in the brain. Peter Kalivas of the Medical University of South Carolina reported at the 2013 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry that most drugs of abuse alter glutamate levels and the plasticity of synapses in the nucleus accumbens, the reward area of the brain. Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, and compulsive habits may be associated with increased release of glutamate in this brain area.

New discoveries in neuroanatomy are helping clarify what addiction looks like in the brain. Peter Kalivas of the Medical University of South Carolina reported at the 2013 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry that most drugs of abuse alter glutamate levels and the plasticity of synapses in the nucleus accumbens, the reward area of the brain. Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, and compulsive habits may be associated with increased release of glutamate in this brain area.

During chronic cocaine administration, for example, the neurons in the nucleus accumbens lose their adaptive flexibility and their ability to respond to signals from the prefrontal cortex. Normally, low levels of stimulation would induce long-term depression (LTD) while high levels of stimulation would induce long-term potentiation (LTP). These are long-term changes in the strength of a synapse, which allow the brain to change with learning and memory. When long-term potentiation and long-term depression are no longer possible, memory and new learning in response to messages from the prefrontal cortex are diminished.

Given this absence of flexible responding, animals extinguished from cocaine self-administration (when a lever they had pressed to receive cocaine ceases to provide cocaine) are highly susceptible to cocaine reinstatement if a stressor is presented or if a signal appears that suggests the availability of cocaine. This cocaine reinstatement is associated with high levels of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens, so Kalivas reasoned accurately that lowering these levels would be associated with a lesser likelihood of cocaine reinstatement.

The drug N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which is available from health food stores, decreases the amount of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens by inducing a glutamate transporter in glial cells that helps clear excess synaptic glutamate. In Kalivas’ research, NAC prevented cocaine reinstatement, cocaine-induced anatomical changes in spine shape (bigger, stubby spines), and the loss of long-term potentiation and long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens.

The findings on NAC in animal studies led to a series of important small placebo-controlled clinical trials in people with a variety of addictions, and positive results have been found using NAC in people addicted to opiates, cocaine, alcohol, marijuana, and gambling. It also decreases hair-pulling in trichotillomania and reduces stereotypy and irritability in children with autism.

NAC also appears to be effective in the treatment of unipolar and bipolar depressed patients in placebo-controlled trials by Australian researcher Michael Berk. Thus, NAC could be useful for patients with affective disorders who are also having difficulties with comorbid substance use.

Some antibiotics (that are not commonly available) also induce the glutamate transporter and glial cells of the nucleus accumbens, offering a potential new approach to treating some addictions.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Tailored For Children and Adolescents

At a symposium on early-onset depression at the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Betsy Kennard described a course of cognitive behavioral therapy tailored to eliminating residual symptoms in children with unipolar depression who had no family history of a parent with bipolar disorder. In the same study Graham Emslie discussed, the investigators considered cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of childhood- and adolescent-onset depression.

The therapy was aimed at achieving health and wellbeing and focusing on positive attributes and strengths in the child, and it was designed to be a shorter than usual course (i.e. four weekly sessions, then four every other week, and one at three months). This regimen typically also included three to five family sessions. Other key components of the therapy included anticipating and dealing with stressors, setting goals, and practicing all the skills learned.

On a visual timeline, children identified and wrote down past stressors, how they felt when depressed, their automatic cognitions, ways they would know when they were feeling down again (i.e. feeling isolated, angry at parents, etc.), their strengths and skills, what obstacles to feeling better existed and how to circumvent them, and their long-term goals.

The therapy was based on the research of Martin Seligman and Giovanni A. Fava, plus Rye’s Six S’s (soothing, self-healing, social, success, spiritual, and self-acceptance). The children participated in practice and skill-building in each domain. Sleep hygiene and exercise were emphasized. The idea of “making it stick” was made concrete with phrases on sticky notes taken home and put up on a mirror. Postcards were even sent between sessions as reminders and for encouragement.

Editor’s Note: Most depressed kids don’t get completely well (only about 20% after an acute course of medication). Something must be added. This kind of specialized cognitive behavior therapy works and keeps patients from relapsing. This study included only those children with unipolar depression whose parents did not have bipolar disorder. However, Emslie noted that depressed children of a bipolar parent also had an exceedingly low rate of switching into mania (2 to 4%) in his experience, so fluoxetine followed by cognitive behavioral therapy might be considered for treating unipolar depressed children of a bipolar parent.

Once children have developed bipolar disorder, evidenced by hypomania or mania followed by depression, antidepressants are to be avoided in favor of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics, since there is a higher switch rate in these youth when they are prescribed antidepressant monotherapy.

Since children with bipolar disorder are at such high risk for continued symptoms and relapses, the strategy of adding cognitive behavioral therapy to their successful drug treatment would appear appropriate for them as well as those with unipolar depression, especially since there is a large positive literature on the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy, psychoeducation, and Family Focused Therapy (FFT) in children and adults with bipolar depression. As noted previously, FFT is very effective for children at high risk because of a parent with bipolar disorder and who are already symptomatic with anxiety, depression or BP-NOS.

Moral of the story: getting kids with unipolar or bipolar depression well and keeping them well is a difficult endeavor that requires specialized, combined medication and therapy approaches and follow-up education and therapy. This is for sure. The hope would also be that good early and long-term intervention would yield a more benign course of recurrent unipolar or bipolar disorder than would treatment as usual (which all too often consists of medication only).

Continuation Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Prevents Relapse in Kids

At a symposium on early-onset depression at the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Graham Emslie of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center discussed the role of cognitive behavioral therapy in the long-term treatment of child-and adolescent-onset unipolar depression.

In Emslie’s research, the combination of the antidepressant fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy reduced depressive relapses in children. Using the two treatments together did not speed onset of antidepressant response compared to fluoxetine alone, but once children responded to the medication, the addition of cognitive behavioral therapy reduced relapses over the next year compared to fluoxetine alone (even though the cognitive behavioral therapy ended after the first six months).

Emslie likened the use of cognitive behavioral therapy to the course of rehabilitation that often follows a major surgery and is meant to sustain or enhance the good effects of surgery. Getting patients to full remission (well and with no residual symptoms) was the key to staying well.

IV Ketamine Superior to IV Midazolam in Adults with PTSD

In a recent study, ketamine performed better than an active comparator on several measures in adults with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Since ketamine has noticeable dissociative effects, researchers have looked for another drug with mind-altering effects that would be a more appropriate comparator than placebo.

At the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Adriana Feder of Mount Sinai Hospital reported on the randomized study in those with PTSD, in which intravenous ketamine was compared to intravenous midazolam, a potent benzodiazepine that produces anti-anxiety and sedating effects. Murrough et al. previously showed that intravenous ketamine was superior to midazolam in treatment-resistant depression.

In the randomized study Feder described, the participants had suffered PTSD from a physical or sexual assault and had been ill for 12 to 14 years. Those who received ketamine improved more, in some instances for as long as two weeks (ketamine’s blood levels disappear after a few hours, and its clinical antidepressant effects usually last only a few days). Reports of side effects included three patients with blood pressure increases requiring treatment with propranolol, and four patients who each had a transient episode of vomiting.

These controlled data parallel previous open observations. When ketamine was used as a surgical anesthetic during operations on burn patients, only 26.9% subsequently reported PTSD compared to 46.4% who developed PTSD when an alternative to ketamine was used as the anesthetic.

Intranasal Ketamine May Be an Alternative to IV in Refractory Depression

At the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kyle Lapidus of Mount Sinai Hospital reviewed the literature from controlled studies on the efficacy of intravenous (IV) ketamine at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg over a 40-minute infusion for adults with treatment-resistant depression (with consistent response rates of 50% or more), and suggested that intranasal ketamine may also be effective.

Ketamine is a strong blocker of the glutamate NMDA receptor. At high doses (6 to 12 mg/kg) it is an anesthetic, at slightly lower doses (3 to 4 mg/kg) it is psychotomimetic (causing psychotic symptoms) and is sometimes used as a drug of abuse, and at very low doses it is a rapidly acting antidepressant, often bringing about results within 2 hours. Antidepressant effects typically last 3 to 5 days, so the question of how to sustain these effects is a major one for the field.

Murrough et al. reported in Biological Psychiatry in 2012 that five subsequent infusions of ketamine sustained the initial antidepressant response and appeared to be well tolerated by the patients. Another NMDA antagonist, riluzole (used for the treatment of ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease), did not sustain the acute effects of ketamine, and now lithium is being studied as a possible strategy for doing so.

The bioavailability of ketamine in the body depends on the way it is administered. Compared to IV administration, intramuscular (IM) administration is painful but results in 93% of the bioavailability of IV ketamine. Intranasal (IN) administration results in 25-50% of the bioavailability of IV administration, while oral administration results in only 16-20% of the bioavailability of IV administration, so Lapidus chose to study the IN route. He compared intranasal ketamine at doses of 50mg (administered in a mist ) to 0.5 ml of intranasal saline. Both were given in two infusions seven days apart. Lapidus observed good antidepressant effects and good tolerability. Papolos et al. had reported earlier that intranasal ketamine had good effects in a small open trial in treatment-resistant childhood onset bipolar disorder.

Editor’s Note: Further studies of the efficacy and tolerability of intranasal ketamine are eagerly awaited.

Depression in Youth Is Tough to Treat and Requires Persistence and Creativity

At a symposium on ketamine for the treatment of depression in children at the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, David Brent, a professor at the University of Pittsburg, gave the opening talk on the fact that as many as 20% of adolescents who are depressed fail to improve, develop chronic illness, and are thus in need of alternatives to traditional treatment. Predictors of non-improvement include substance use, low-level manic symptoms, poor adherence to a medication regimen, low blood levels of antidepressants, family conflict, high levels of inflammation in the body, and importantly, maternal depression. In adolescents insomnia was associated with poor response, but in younger children insomnia was associated with a better response.

At a symposium on ketamine for the treatment of depression in children at the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, David Brent, a professor at the University of Pittsburg, gave the opening talk on the fact that as many as 20% of adolescents who are depressed fail to improve, develop chronic illness, and are thus in need of alternatives to traditional treatment. Predictors of non-improvement include substance use, low-level manic symptoms, poor adherence to a medication regimen, low blood levels of antidepressants, family conflict, high levels of inflammation in the body, and importantly, maternal depression. In adolescents insomnia was associated with poor response, but in younger children insomnia was associated with a better response.

Brent suggested using melatonin and sleep-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in youth, but not using trazodone (which is commonly prescribed). Trazodone is converted to a compound called Meta-chlorophenylpiperazine or MCPP, which induces anxiety and dysphoria. MCPP is metabolized by hepatic enzymes 2D6, and fluoxetine and paroxetine inhibit 2D6, so if trazodone is combined with these antidepressants, the patient may get too much MCPP.

Surprisingly and contrary to some data in adults about the positive effects of therapy in those with abuse histories, in the study TORDIA (Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents), if youth with depression had experienced abuse in childhood, they did less well on the combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared to SSRIs alone.

Extra Folate in Those Taking L-Methylfolate Could Be Counterproductive

While the nutritional supplement folate (also known as folic acid or vitamin B9) can be useful for depression, there appears to be one instance when augmentation with regular folate could be counterproductive. In those with a transport defect associated with a MTHR (methyl tetrahydrofolate reductase) deficiency, folate can compete with l-methylfolate for uptake into the brain. Folate would thus limit the beneficial effects of l-methylfolate supplementation, which is required for this 15% of the population.

Investigating Relapse after ECT

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective treatment for patients with treatment-resistant depression, but still many patients relapse after the treatment. Medications can prolong the period of remission, but even so, relapse rates have increased in recent decades (probably at least partly because ECT was once a standard initial treatment but is now only used with those patients with the most difficult-to-treat illnesses.) A 2013 meta-analysis by Jelovac et al. in Neuropsychopharmacology reviewed existing research on relapse and which medications might be able to best prolong remission after ECT.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective treatment for patients with treatment-resistant depression, but still many patients relapse after the treatment. Medications can prolong the period of remission, but even so, relapse rates have increased in recent decades (probably at least partly because ECT was once a standard initial treatment but is now only used with those patients with the most difficult-to-treat illnesses.) A 2013 meta-analysis by Jelovac et al. in Neuropsychopharmacology reviewed existing research on relapse and which medications might be able to best prolong remission after ECT.

The researchers analyzed 32 studies that each included at least 2 years of followup. In studies from the recent era in which patients received continuation treatment with medication following ECT, 51.1% of patients relapsed within a year, and the majority of those (37.7%) relapsed within the first 6 months after ECT. Among patients treated with continuation ECT, a similar proportion (37.2%) also relapsed within 6 months of the initial ECT treatment. In randomized controlled trials, treatment with antidepressants with or without lithium following ECT halved the rate of relapse within 6 months compared to placebo.

Even with continuing intermittent ECT treatment, risk of relapse remains high, especially within the first 6 months. The authors concluded that maintenance of wellbeing following ECT must be improved.

Editor’s Note: One possibility for prolonging remission is the more intensive continuation regimen using right unilateral ultrabrief pulse ECT suggested by Nordenskjöld et al. in the Journal of ECT in 2013. Continuation treatment with a combination of ECT and medication resulted in 6-month relapse rates of 29% (compared to 54% with medication alone) and one-year relapse rates of 32% (compared to 61%).

New Research on Ketamine

The drug ketamine can produce antidepressant effects within hours when administered intravenously.

The drug ketamine can produce antidepressant effects within hours when administered intravenously.

Finding an Appropriate Control

Comparing ketamine to placebo has challenges because ketamine produces mild dissociative effects (such as a feeling of distance from reality) that are noticeable to patients. At the 2013 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, James W. Murrough and collaborators at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine reported their findings from the first controlled trial of intravenous ketamine in depression that uses an active control, the short-acting benzodiazepine midazolam, which has sedative effects and decreases anxiety, but is not known as an antidepressant. On virtually all measures intravenous ketamine was a more effective antidepressant following 2 infusions per week.

These data help dispel one of the criticisms of intravenous ketamine, that studies of the drug have not been sufficiently blinded (when patients and medical staff are kept from knowing which patients receive an active treatment and which are in the placebo control group) and that the lack of an appropriate active placebo contributed to the dramatic findings about ketamine’s antidepressant effects. It now appears that these criticisms have been appropriately answered and that intravenous ketamine is highly effective not only in comparison to placebo but also to an active comparator.

This research was presented as a poster at the meeting and published as abstract #442 in the meeting supplement to the journal Biological Psychiatry, Volume 73, Number 9S, and was also published in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 2013.

Slowing Down Ketamine Infusions to Reduce Side Effects

Ketamine is commonly given in 40-minute intravenous infusions. Timothy Lineberry from the Mayo Clinic reported in Abstract #313 from the meeting that slower infusions of ketamine over 100 minutes were also effective in producing antidepressant effects in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Lineberry’s research group used the slower infusion in order to increase safety and decrease side effects, such as the dissociative effects discussed above. In the 10 patients the group studied, they observed a response rate of 80% and a remission rate of 50% (similar to ketamine’s effects with 40-minute infusions).

Family or Personal History of Alcohol Dependence Predicts Positive Response to Ketamine in Depression

Mark J. Niciu and collaborators at the NIMH reported in Abstract #326 that a personal or family history of alcohol dependence predicted a positive response to IV ketamine in patients with unipolar depression.

Ketamine Acts on Monoamines in Addition to Glutamate

Ketamine’s primary action in the nervous system is to block glutamate NMDA receptors in the brain. In addition to its effects on glutamate, it may also affect the monoamines norepinephrine and dopamine. Kareem S. El Iskandarani et al. reported in Abstract #333 that in a study of rats, ketamine increased the firing rate of norepinephrine neurons in a part of the brain called the locus coeruleus and also increased the number of spontaneous firing dopamine cells in the ventral tegmental area of the brain.

Editor’s Note: These data showing that ketamine increased the activity of two monoamines could help explain ketamine’s ability to induce rapid onset of antidepressant effects, in addition to its ability to immediately increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, important for long-term memory and the creation of new synapses) and to restore healthy mushroom-shaped spines on the dendrites of neurons in the prefrontal cortex.

Jules Angst on the Long-Term Progressive Course of Mood Disorders

At a symposium celebrating the retirement of Willem Nolen, a researcher who spent 40 years studying unipolar and bipolar disorder, from his position at Groningen Hospital in the Netherlands, his colleague Jules Angst discussed some recent findings. Angst is perhaps the world’s leading authority on the long-term course of unipolar and bipolar disorders based on his multiple prospective follow-up studies, some lasting 20-30 years.

The Sensitization-Kindling Model

Angst described evidence that supports the sensitization-kindling model of recurrent mood disorders, which this editor (Robert Post) described in 1992. Episodes tend to recur faster over time, i.e. the well interval between episodes becomes progressively shorter. While stressors often precipitate initial episodes, after multiple occurrences, episodes also begin to occur spontaneously (in the absence of apparent stressors).

This type of progressive increase in response to repetition of the same stimulus was most clearly seen in animal studies, where repeated daily electrical stimulation of the amygdala eventually produced major motor seizures (i.e. amygdala kindling). Daily electrical stimulation of rodents’ amygdala for one second initially produced no behavioral change, but eventually, minor and then full-blown seizures emerged. Once enough of the stimulated full-blown amygdala-kindled seizures had occurred, seizures began to occur spontaneously (i.e. in the absence of the triggering stimulation).

The analogy to human mood disorders is indirect, but kindling provides a model not only for how repeated triggers eventually result in full-blown depressive episodes, but also for how these triggered depressive episodes may eventually occur spontaneously as well.

Long-Term Treatment of Mood Disorders

Angst also discussed long-term treatment of mood disorders. He has found that long-term lithium treatment not only reduces suicides in patients with bipolar disorder, but also reduces the medical mortality that accompanies bipolar disorder.

Angst noted his previous surprising observations that in unipolar disorder, long-term maintenance treatment, even with low doses of tricyclic antidepressants, prevents suicide. Previously, researchers Ellen Frank and David Kupfer of Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center had found that when patients with recurrent unipolar depression who had been stable for 5 years on the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline were blindly switched to half their original dose, about 90% rapidly relapsed into a new episode of depression. Their data helped establish the prevailing view that maintenance treatment with the full-dose regimen required to achieve a good initial acute response is also the optimal approach to long-term continuation and prophylactic treatment.

Angst found good results even at low doses, but his data may not be in conflict with Frank and Kupfer’s, as a person who responds well acutely to low doses may also be able to maintain good enough response to them to prevent recurrences in the long term.

Incidence of Bipolar Disorder in Adolescents Similar to Incidence in Adults

Angst also presented data from the Adolescent Supplement to the National Comorbidity Study (NCS-A), which analyzed interviews with approximately 10,000 adolescents (aged 13-17) in the US. He found a 7.6% incidence of major depression, a 2.5% incidence of bipolar I or II disorder, and a 1.7% incidence of mania. There was an even higher incidence of sub-threshold bipolar disorder, when there are not enough symptoms or a long enough duration of symptomatology to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar I or II disorder. These data published by Merikangas et al. in 2009 provide clear epidemiological data that there is a substantial incidence of bipolar disorder in adolescents in the US, roughly similar to that seen in adults.