Reduced Cognitive Function and Other Abnormalities in Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

At the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Ben Goldstein described a study of cognitive dysfunction in pediatric bipolar disorder. Children with bipolar disorder were three years behind in executive functioning (which covers abilities such as planning and problem-solving) and verbal memory.

At the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Ben Goldstein described a study of cognitive dysfunction in pediatric bipolar disorder. Children with bipolar disorder were three years behind in executive functioning (which covers abilities such as planning and problem-solving) and verbal memory.

There were other abnormalities. Youth with bipolar disorder had smaller amygdalas, and those with larger amygdalas recovered better. Perception of facial emotion was another area of weakness for children (and adults) with bipolar disorder. Studies show increased activity of the amygdala during facial emotion recognition tasks.

Goldstein reported that nine studies show that youth with bipolar disorder have reduced white matter integrity. This has also been observed in their relatives without bipolar disorder, suggesting that it is a sign of vulnerability to bipolar illness. This could identify children who could benefit from preemptive treatment because they are at high risk for developing bipolar disorder due to a family history of the illness.

There are some indications of increased inflammation in pediatric bipolar disorder. CRP, a protein that is a marker of inflammation, is elevated to a level equivalent to those in kids with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis before treatment (about 3 mg/L). CRP levels may be able to predict onset of depression or mania in those with minor symptoms, and is also associated with depression duration and severity. Goldstein reported that TNF-alpha, another inflammatory marker, may be elevated in children with psychosis.

Goldstein noted a study by Ghanshyam Pandey that showed that improvement in pediatric bipolar disorder was related to increases in BDNF, a protein that protects neurons. Cognitive flexibility interacted with CRP and BDNF—those with low BDNF had more cognitive impairment as their CRP increased than did those with high BDNF.

Offspring of Parents with Psychiatric Disorders At Increased Risk for Disorders of Their Own

At a symposium at the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorder, researcher Rudolph Uher discussed FORBOW, his study of families at high risk for mood disorders. Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and severe depression are at higher risk for a variety of illnesses than offspring of healthy parents.

Uher’s data came from a 2014 meta-analysis by Daniel Rasic and colleagues (including Uher) that was published in the journal Schizophrenia Bulletin. The article described the risks of developing mental illnesses for 3,863 offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression compared to offspring of parents without such disorders.

Previous literature had indicated that offspring of parents with severe mental illness had a 1-in-10 likelihood of developing a severe mental illness of their own by adulthood. Rasic and colleagues suggested that the risk may actually be higher—1-in-3 for the risk of developing a psychotic or major mood disorder, and 1-in-2 for the risk of developing any mental disorder. An adult child may end up being diagnosed with a different illness than his or her parents.

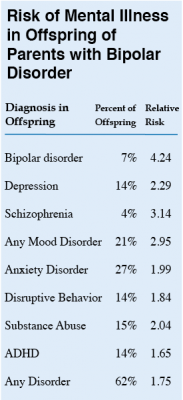

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

At the symposium, Uher focused on families in which a parent had bipolar disorder. These families made up 1,492 of the offspring in the Rasic study. The table at right shows the risk of an illness among the offspring of bipolar parents compared to that risk among offspring of healthy parents, otherwise known as relative risk. (For example, offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are 4.24 times more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder themselves than are offspring of non-bipolar parents.) The table also shows the percentage of offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who have each type of disorder.

Editor’s Note: These data emphasize the importance of vigilance for problems in children who are at increased risk for mental disorders because they have a family history of mental disorders. One way for parents to better track mood and behavioral symptoms is to join our Child Network.

Treating Bipolar Disorder in Children and Adolescents

Bipolar disorder in childhood or adolescence can destroy academic, family, and peer relationships and increase vulnerability to drug use, unsafe sexual encounters, disability, and suicide. Treatment is critical to avoid cognitive decline. Given the potential tragic outcomes of undertreating bipolar illness, it is concerning that 40–60% of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder are not in treatment.

In a talk at the 2015 meeting of the International Society for Bipolar Disorder, researcher Cristian Zeni reviewed the existing research on the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. A 2012 study by Geller reported response rates of 68% for the atypical antipsychotic risperidone, 35% for lithium and 24% for valproate. Risperidone was linked to weight gain and increases in prolactin, a protein secreted by the pituitary gland, while lithium was linked to more discontinuations and valproate to sedation.

For children or adolescents with aggression, researcher Robert Kowatch recommends quetiapine, aripiprazole, and risperidone. For those with a family history of bipolar disorder, he recommends lithium or alternatively, valproate plus an atypical antipsychotic.

Reseacher Robert Findling has found that lamotrigine has positive effects in childhood mania, and Duffy et al. found in a study of 21 children with mania that 13 remained stable on monotherapy with quetiapine for 40 weeks without relapse, while 5 others required combination treatment with more than one drug. In studies by Karen Wagner, oxcarbazepine was significantly better than placebo at reducing mania in younger children (ages 7–12), but not older children (13–18).

Studies by Duffy and colleagues in 2007 and 2009 recommend lithium for those with a family history of bipolar disorder, atypical antipsychotics for children with no family history of bipolar disorder, and lamotrigine for those with a family history of anxiety disorders.

In children with bipolar disorder and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, there is universal agreement that mood should be stabilized first, and then small amounts of stimulants may be added for residual ADHD symptoms. Too often, the opposite occurs, with stimulants given prior to mood stabilization with lithium, anticonvulsants (valproate, lamotrigine, carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine) and/or an atypical antipsychotic. Read more

Several Types of Psychotherapy Effective in Childhood Bipolar Disorder

Childhood onset bipolar disorder can be highly impairing. Treatment usually includes medication, but several types of psychotherapy have also been found to be superior to treatment as usual. These include family focused therapy, dialectical behavior therapy and multifamily psychoeducation groups, including Rainbow therapy.

Family focused therapy, developed by David Miklowitz, consists of psychoeducation about bipolar disorder and the importance of maintaining a stable medication routine. Families are taught to recognize early symptoms of manic and depressive episodes, and how to cope with them. Families also learn communication and problem solving skills that can prevent stressful interactions.

Dialectical behavior therapy was developed by Marsha Linehan, initially for the treatment of borderline personality disorder. It can be useful in bipolar disorder because participants learn how to manage stressors that might otherwise trigger depression or mania. DBT teaches five skills: mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and self management.

Multifamily psychoeducation was developed by Mary Fristad. In groups, children and parents learn about mood disorders, including how to manage symptoms, and also work on communication, problem solving, emotion regulation, and decreasing family tension.

Rainbow therapy is a type of multifamily approach also known as child and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (CFF CBT). It integrates individual cognitive-behavioral therapy with family psychoeducation and mindfulness skills training. In a recent article in the journal Evidence Based Mental Health, Miklowitz reviewed the current research on Rainbow therapy. While the research to date has many limitations, he highlighted some benefits of Rainbow therapy: its flexibility, and its focus on treating parents’ symptoms along with children’s illness.

Lithium Safely Reduces Mania in Kids 7–17

The first large, randomized, double-blind study of lithium in children and teens has shown that as in adults, the drug can reduce mania with minimal side effects. The study by researcher Robert Findling was published in the journal Pediatrics in October. Lithium is the best available treatment for adults, but until now little research had been done on treatments for children and teens with bipolar disorder.

In the study, 81 participants between the ages of 7 and 17 with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and manic or mixed episodes were randomized to receive either lithium or placebo for a period of eight weeks. By the end of the study, those patients taking lithium showed greater reductions in manic symptoms than those taking placebo. Among those taking lithium, 47% scored “much improved” or “very much improved” on a scale of symptom severity, compared to 21% of those taking placebo.

Dosing began at 900mg/day for most participants. (Those weighing less than 65 lbs. were started at 600mg/day.) Dosing could be gradually increased. The mean dose for patients aged 7–11 was 1292mg/day, and for patients aged 12–17 it was 1716mg/day.

Side effects were minimal. There were no significant differences in weight gain between the two groups. Those taking lithium had significantly higher levels of thyrotropin, a peptide that regulates thyroid hormones, than those taking placebo. If thyroid function is affected in people taking lithium, the lithium dosage may be decreased, or patients may be prescribed thyroid hormone.

Saphris Reformulated for Kids with Bipolar I

The atypical antipsychotic asenapine has been reformulated for bipolar I disorder in children aged 10–17. The drug (trade name Saphris) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009 for adults with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It is sometimes used as a treatment for mixed episodes (depression with some symptoms of mania).

The new formulation consists of 2.5mg tablets that are taken sublingually (under the tongue), and are available in a black cherry flavor. These can be prescribed as monotherapy for the acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes in children and teens.

Primates Shed Light on the Neurobiology of Anxiety Disorders in Children

Studies of primates suggest that the amygdala plays an important role in the development of anxiety disorders. Researcher Ned Kalin suggested at the 2015 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry that the pathology of anxiety begins early in life. When a child with anxiety faces uncertainty, the brain increases activity in the amygdala, the insula, and the prefrontal cortex. Children with an anxious temperament, who are sensitive to new social experiences, are at almost sevenfold risk of developing a social anxiety disorder, and later experiencing depression or substance abuse.

A study by Patrick H. Roseboom and colleagues presented at the meeting was based on the finding that corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) plays a role in stress and is found in the central nucleus of the amygdala (as well as in the hypothalamus). The researchers used viral vectors to increase CRH in the central nucleus of the amygdala in young rhesus monkeys, hoping to determine what impact increased CRH has on a young brain. Rhesus monkeys and humans share similar genetic and neural structures that allow for complex social and emotional functioning.

Roseboom and colleagues compared the temperaments of five monkeys who received injections increasing the CRH in their amygdala region to five monkeys who received control injections. As expected, the monkeys with increased CRH showed increases in anxious temperament. Brain scans also revealed increases in metabolism not only in the central nucleus of the amygdala, but also in other parts of the brain that have been linked to anxiety, including the orbitofrontal cortex, the hippocampus, and the brainstem, in the affected monkeys. The degree of increase in amygdala metabolism was directly proportional to the increase in anxious temperament in the monkeys, further linking CRH’s effects in the amygdala to anxiety.

Studies of Medications and RTMS in Children Lacking

At the 2015 meeting of the Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Society in May, researcher Stephanie Ameis discussed the dearth of medication studies in children, particularly for depression but also for schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders, which share the symptom of impaired executive functioning, which can include skills such as planning and problem solving.

Ameis noted that in a literature review, there were a total of 1046 controlled pharmacological treatment studies in adults compared to only 106 in children, which reflects a relative absence of treatment knowledge, especially for depression (where there were 303 studies in adults versus only 17 in children) and bipolar disorder (where there were 174 studies of adults and 24 of children).

Ameis then reviewed the few studies of rTMS for depression in young people. She identified several series with only a total of 33 children and adolescents who had been treated with rTMS. She is beginning to study rTMS in patients with high-functioning autism (40 patients aged 16 to 25 have been randomized in her study). Ameis also described a 2013 study of rTMS in which patients with schizophrenia showed improved performance on a test of working memory published by Mera S. Barr and colleagues in the journal Biological Psychiatry. Ameis cited this as a rationale for studying rTMS’s effect on cognitive performance in people with autism.

RTMS Study Identifies Glutamate as a Biomarker for Depression Treatment

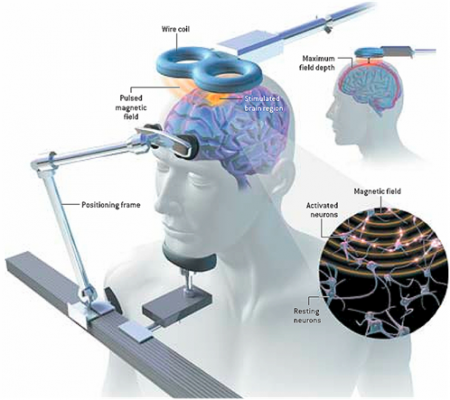

At the 3rd Annual Meeting of the Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Society, Canadian researcher Frank MacMaster discussed his study of repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in 50 children with depression. RTMS is a non-invasive procedure in which an electromagnetic coil is placed against the side of the forehead and magnetic pulses that can penetrate the scalp are converted into small electrical currents that stimulate neurons in the brain. The study was designed to identify biomarkers, or characteristics that might indicate which patients were likely to respond to the treatment. All of the patients received rTMS at a frequency of 10 Hz. Using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) technology, MacMaster found that children who responded well to rTMS treatment had low levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate at the beginning of the study, but their glutamate levels increased as their depression improved. Children who didn’t improve had higher glutamate levels at the beginning of the study, and these fell during the rTMS treatment.

At the 3rd Annual Meeting of the Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Society, Canadian researcher Frank MacMaster discussed his study of repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in 50 children with depression. RTMS is a non-invasive procedure in which an electromagnetic coil is placed against the side of the forehead and magnetic pulses that can penetrate the scalp are converted into small electrical currents that stimulate neurons in the brain. The study was designed to identify biomarkers, or characteristics that might indicate which patients were likely to respond to the treatment. All of the patients received rTMS at a frequency of 10 Hz. Using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) technology, MacMaster found that children who responded well to rTMS treatment had low levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate at the beginning of the study, but their glutamate levels increased as their depression improved. Children who didn’t improve had higher glutamate levels at the beginning of the study, and these fell during the rTMS treatment.

MacMaster hopes that glutamate levels and other biological indicators such as inflammation will eventually pinpoint which treatments are likely to work best for children with depression. At the meeting, MacMaster said that in Canada, only a quarter of the 1,200,000 children with depression receive appropriate treatment for it. Very little funding is devoted to research on children’s mental health, a serious deficit when one considers that most depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, oppositional behavior, conduct disorder, and substance abuse begins in childhood and adolescence, and early onset of these illnesses has been repeatedly linked to poorer outcomes.

Editor’s Note: The strategy of identifying biomarkers is an important one. MacMaster noted that this type of research is possible due to the phenomenal improvements in brain imaging techniques that have occurred over the past several decades. These techniques include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to a resolution of 1 mm; functional MRI; diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which can depict the connectivity of white matter tracts; and spectroscopy, which can be used to identify chemical markers of neuronal health and inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters, and analyze membrane integrity and metabolic changes. These methods provide exquisite views of the living brain, the most complicated structure in the universe. The biomarkers these techniques may identify will allow clinicians to predict how a patient will respond to a given treatment, to choose treatments more rapidly, and to treat patients more effectively.

Surprisingly, Adult ADHD Is Distinct From Childhood ADHD

In a longitudinal study of 1,037 people born in Dunedin, New Zealand in 1972 and 1973, most participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adulthood did not have the disorder as children. The study by Terrie E. Moffitt and colleagues in the American Journal of Psychiatry is the first prospective longitudinal study to describe the childhood of adults with ADHD.

When the study participants were children, about 6% were diagnosed with ADHD (mostly males). These children also had comorbid disorders, neurocognitive deficits, multiple genes associated with risk for ADHD, and some life impairment when they reached adulthood.

In adulthood, about 3% of the participants had ADHD (roughly equal between men and women), and 90% of these participants had no history of ADHD in childhood. The participants with ADHD in adulthood also had substance dependence and life impairment, and had sought treatment for the disorder. The researchers were surprised to find that these participants with adult ADHD did not show neuropsychological deficits in childhood, nor did they have the genetic risk factors associated with childhood ADHD.

If the findings of this study are replicated, researchers will have to rethink the current classification of ADHD as a neurodevelopment disorder that begins in childhood, and begin to determine how adult ADHD develops.

Editor’s Note: Before the publication of this article, most investigators (including this editor Robert M. Post) thought that virtually all ADHD in adulthood evolved from the childhood disorder, and if it did not begin in childhood, the diagnosis was suspect. I still believe the ADHD that appears in adulthood in patients with bipolar disorder is likely attributable to residual depression and anxiety or hypomania and that more concerted treatment of the patient to full remission will often result in much better attention, concentration, and ability to follow through and stay on task.