Connections Between Stress and Substance Use May Be Mediated By Corticotropin-Releasing Factor

Researchers hope to map out the neurocircuitry by which stress leads to compulsive drug taking. A recent study by Klaus Miczek and colleagues examined different rodents’ responses to the stress of being repeatedly placed in the cage of a larger, more aggressive rodent, developing what is known as defeat stress, a set of behaviors that mimic human depression. Mice and rats showed increases in the stress hormone corticosterone that did not diminish over repeated run-ins with a larger animal. Rodents who were exposed to this stress became sensitized to cocaine or amphetamine, showing hyperactivity that increased each time they accessed the drug (the opposite of a tolerance response). Some also “binged” on cocaine, which they were able to self-administrate by pushing a lever to receive infusions. The mice and rats that went through the social defeat showed elevated levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, the brain’s reward center. Levels were related to the severity of their stressful experience.

Researchers hope to map out the neurocircuitry by which stress leads to compulsive drug taking. A recent study by Klaus Miczek and colleagues examined different rodents’ responses to the stress of being repeatedly placed in the cage of a larger, more aggressive rodent, developing what is known as defeat stress, a set of behaviors that mimic human depression. Mice and rats showed increases in the stress hormone corticosterone that did not diminish over repeated run-ins with a larger animal. Rodents who were exposed to this stress became sensitized to cocaine or amphetamine, showing hyperactivity that increased each time they accessed the drug (the opposite of a tolerance response). Some also “binged” on cocaine, which they were able to self-administrate by pushing a lever to receive infusions. The mice and rats that went through the social defeat showed elevated levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, the brain’s reward center. Levels were related to the severity of their stressful experience.

Later the rodents had a choice between water and a 20% alcohol solution. The researchers determined what type of stress led the rodents to consume the alcohol solution instead of the water. The maximal effect was seen in two types of mice that suffered an attack of less than five minutes that resulted in a moderate number of attack bites (30); this resulted in the mice consuming large amounts (15–30 g/kg/day) of the alcohol solution. Earlier sensitization to cocaine or amphetamine did not predict later alcohol or cocaine self-administration.

When the researchers injected the rodents with antagonists of the receptors for corticotropin-releasing factor, a hormone and neurotransmitter important in stress response, prior to each episode of social defeat, the rodents did not escalate their cocaine or alcohol self-administration, indicating that CRF plays an essential role in the process by which stress makes animals prone to using substances.

In related research by Camilla Karlsson and colleagues, IL-1R1 and TNF-1R, the receptors for two inflammatory cytokines, mediated the effects of social stress on escalated alcohol use in mice.

Oxytocin Can Block Stress-Induced Relapse of Cocaine Seeking in Animals

Stress can trigger former drug users to begin taking drugs again. In clinical trials, the bonding hormone oxytocin has been found to reduce stress-induced cravings for certain drugs, including alcohol and marijuana. A new study in animals suggests that oxytocin may be able to reduce stress-induced cocaine cravings as well.

Brandon Bentzley and colleagues combined an unpredictable shock to the foot with an alkaloid called yohimbe that comes from a particular tree bark to apply stress to animals who had previously developed a cocaine self-administration habit that had since been extinguished. The combination of the foot shocks and yohimbe brought back robust reinstatement of the animals’ cocaine seeking behaviors, but pretreatment with oxytocin (at doses of 1 mg/kg) prevented this reinstatement.

This research suggests that oxytocin has potential to prevent stress-induced cocaine cravings in people.

Learning to Change Brain Activity to Decrease Cocaine Craving

Colleen Hanlon, a researcher at the Medical University of South Carolina, has found that biofeedback can be used to decrease cocaine craving in people with substance abuse problems. In her research, patients were given real time feedback from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and learned to decrease the activation of a part of the brain called the anterior cingulate when exposed to cocaine cues (reminders of their desire for cocaine). They were able to decrease drug craving as well as heart rate and skin conduction, which often accompany it.

Fear Memories Can Be Erased or Provoked in Animals

Researchers have identified neurons responsible for remembering conditioned fear in the amygdala of rodents, and can turn them on and off. At the 2013 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, Sheena A. Josselyn gave a breath-taking presentation on this process.

When animals hear a tone they have learned to associate with the imminent delivery of a shock in a given environment, they learn to avoid that environment, and they reveal their learning of the tone-shock association by freezing in place. Josselyn was able to observe that 20% of the neurons in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala were involved in this memory trace. They were revealed by their ability to increase the transcription factor CREB, which is a marker of cell activation. Using cutting-edge molecular genetic techniques, the researchers could selectively eliminate only these CREB-expressing neurons (using a new technology in which a diphtheria toxin is attached to designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs, or DREADDs) and consequently erase the fear memory.

The researchers could also temporarily inhibit the memory, by de-activating the memory trace cells, or induce the memory, so that the animal would freeze in a new context. Josselyn and colleagues were able to identify the memory trace for two different tones in two different populations of amygdala neurons.

The same molecular tricks with memory also worked with cocaine cues, using what is known as a conditioned place preference test. A rodent will show a preference for an environment where it received cocaine. Knocking out the selected neurons would remove the memory of the cocaine experience, erasing the place preference.

The memory for cocaine involved a subset of amygdala neurons that were also involved in the conditioned fear memory trace. Incidentally, Josselyn and her group were eventually able to show that amygdala neurons were in competition with each other as to whether they would be involved in the memory trace for conditioned fear or for the conditioned cocaine place preference.

Treating Substance Abuse: A Step Forward

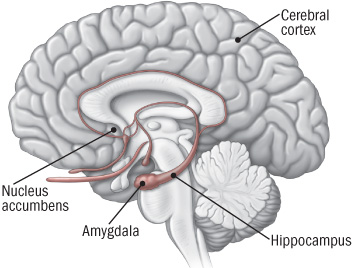

New discoveries in neuroanatomy are helping clarify what addiction looks like in the brain. Peter Kalivas of the Medical University of South Carolina reported at the 2013 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry that most drugs of abuse alter glutamate levels and the plasticity of synapses in the nucleus accumbens, the reward area of the brain. Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, and compulsive habits may be associated with increased release of glutamate in this brain area.

New discoveries in neuroanatomy are helping clarify what addiction looks like in the brain. Peter Kalivas of the Medical University of South Carolina reported at the 2013 meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry that most drugs of abuse alter glutamate levels and the plasticity of synapses in the nucleus accumbens, the reward area of the brain. Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, and compulsive habits may be associated with increased release of glutamate in this brain area.

During chronic cocaine administration, for example, the neurons in the nucleus accumbens lose their adaptive flexibility and their ability to respond to signals from the prefrontal cortex. Normally, low levels of stimulation would induce long-term depression (LTD) while high levels of stimulation would induce long-term potentiation (LTP). These are long-term changes in the strength of a synapse, which allow the brain to change with learning and memory. When long-term potentiation and long-term depression are no longer possible, memory and new learning in response to messages from the prefrontal cortex are diminished.

Given this absence of flexible responding, animals extinguished from cocaine self-administration (when a lever they had pressed to receive cocaine ceases to provide cocaine) are highly susceptible to cocaine reinstatement if a stressor is presented or if a signal appears that suggests the availability of cocaine. This cocaine reinstatement is associated with high levels of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens, so Kalivas reasoned accurately that lowering these levels would be associated with a lesser likelihood of cocaine reinstatement.

The drug N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which is available from health food stores, decreases the amount of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens by inducing a glutamate transporter in glial cells that helps clear excess synaptic glutamate. In Kalivas’ research, NAC prevented cocaine reinstatement, cocaine-induced anatomical changes in spine shape (bigger, stubby spines), and the loss of long-term potentiation and long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens.

The findings on NAC in animal studies led to a series of important small placebo-controlled clinical trials in people with a variety of addictions, and positive results have been found using NAC in people addicted to opiates, cocaine, alcohol, marijuana, and gambling. It also decreases hair-pulling in trichotillomania and reduces stereotypy and irritability in children with autism.

NAC also appears to be effective in the treatment of unipolar and bipolar depressed patients in placebo-controlled trials by Australian researcher Michael Berk. Thus, NAC could be useful for patients with affective disorders who are also having difficulties with comorbid substance use.

Some antibiotics (that are not commonly available) also induce the glutamate transporter and glial cells of the nucleus accumbens, offering a potential new approach to treating some addictions.

Selective Erasure Of Cocaine Memories In A Subset Of Amygdala Neurons

We have written before about the link between memory and both fear and addiction. At a recent scientific meeting, researchers discussed attempts to erase cocaine-cue memories in mice.

In articles published in Science in 2007 and 2009, Han et al. showed that about 20% of neurons in the lateral amygdala of mice were involved in the formation of a fear memory, and that selective deletion of these neurons could erase the fear memory. Using the same methodology, Josh Sullivan et al. identified neurons that were active in the mouse brain during cocaine conditioning. Amygdala activity showed that the mice preferred an environment where they received cocaine to an environment where they didn’t. The researchers noticed increased cyclic AMP, a messenger that led to increased production of calcium responsive element binding protein (CREB). When the researchers targeted the neurons in the lateral amygdala that were overexpressing CREB, they found that selective destruction of the overexpressing neurons disrupted the cocaine-induced place preference.

The research team further documented this effect by temporarily, rather than permanently, knocking out neuronal function. They could reversibly turn off neurons with an inert compound that promotes neuronal inhibition. Silencing the neurons that were overexpressing CREB before the conditioned place preference testing also limited cocaine-induced place preference memory.

Editor’s Note: While this type of intervention is not feasible in humans with cocaine addiction, these data do shed more light on the mechanisms behind cocaine conditioning.

We have written before that if extinction training to break a cocaine habit or neutralize a learned fear is performed within the brain’s memory reconsolidation window (five minutes to one hour after memory recall), it can induce long-lasting alterations in cocaine craving or conditioned fear.

It is possible that properly timed extinction of cocaine- or fear-conditioned memories might work similarly to the selective silencing of neurons that was carried out in the mice using a drug that inhibited CREB-activated neurons. Determining the commonalities between these ways of eliminating conditioned memories could lead to a whole new set of psychotherapeutic approaches to anxiety disorder, addictions, and other pathological habits.

The Amygdala Plays a Role in Habitual Cocaine Seeking

At a recent scientific meeting, Jennifer E. Murray et al. presented findings about the amygdala’s role in habitual cocaine seeking. The amygdala is the part of the brain that makes associations between a stimulus and a response. When a person begins using cocaine, a signal between the amygdala and the ventral striatum (also known as the nucleus accumbens), the brain’s reward center, creates a pleasurable feeling for the person. The researchers found that in mice who have learned to self-administer cocaine, as an animal progresses from intermittent use to habitual use, the amygdala connections shift away from the ventral striatum toward the dorsal striatum, a site for motor and habit memory. If amygdala connections to the dorsal striatum are severed, the pattern of compulsive cocaine abuse does not develop.

At a recent scientific meeting, Jennifer E. Murray et al. presented findings about the amygdala’s role in habitual cocaine seeking. The amygdala is the part of the brain that makes associations between a stimulus and a response. When a person begins using cocaine, a signal between the amygdala and the ventral striatum (also known as the nucleus accumbens), the brain’s reward center, creates a pleasurable feeling for the person. The researchers found that in mice who have learned to self-administer cocaine, as an animal progresses from intermittent use to habitual use, the amygdala connections shift away from the ventral striatum toward the dorsal striatum, a site for motor and habit memory. If amygdala connections to the dorsal striatum are severed, the pattern of compulsive cocaine abuse does not develop.

Editor’s Note: These data indicate that the amygdala is involved in cocaine-related habit memory, and that the path of activity shifts from the ventral to the dorsal striatum as the cocaine use becomes more habit-based—automatic, compulsive, and outside of the user’s awareness.

As we’ve reviewed before, the amygdala also plays a role in context-dependent fear memories, such as those that occur in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The process of retraining a person with PTSD to view a stimulus without experiencing fear is called extinction training. A study by Agren et al. published in Science in 2012 demonstrated that when extinction training of a learned fear took place within the brain’s memory reconsolidation window (five minutes to one hour after active memory recall), the training was sufficient to not only “erase the conditioned fear memory trace in the amygdala, but also decrease autonomic evidence of fear as revealed in skin conductance changes in volunteers.”

The preclinical data presented by Murray and colleagues suggest the possibility that amygdala-based habit memory traces could also be revealed via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in subjects with cocaine addiction. Attempts at extinction of cocaine craving, if administered within the memory reconsolidation window, might likewise be able to erase the cocaine addiction/craving memory trace, as Xue et al. reported in Science in 2012.

Clarifying the Mechanism of Action of N-Acetylcysteine (NAC)

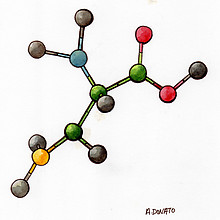

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a drug available over-the-counter in health food stores that seems to be effective for a variety of disorders, including depression and many different habits and addictions. Preventing relapse of cocaine abuse is one of its uses. Researcher Kathryn Reissner at the Medical University of South Carolina found that NAC increases the expression of a glial glutamate transporter (GLT-1) that helps clear excessive glutamate in the nucleus accumbens, and that this mechanism is critical to preventing the reinstatement of cocaine self-administration in rodents.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a drug available over-the-counter in health food stores that seems to be effective for a variety of disorders, including depression and many different habits and addictions. Preventing relapse of cocaine abuse is one of its uses. Researcher Kathryn Reissner at the Medical University of South Carolina found that NAC increases the expression of a glial glutamate transporter (GLT-1) that helps clear excessive glutamate in the nucleus accumbens, and that this mechanism is critical to preventing the reinstatement of cocaine self-administration in rodents.

As we have previously described in the BNN, NAC also decreases cued release of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens by potentiating the cystine-glutamate exchanger. This initially increases extrasynaptic glutamate, but subsequently downregulates glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens through actions at an inhibitory presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptor.

However, the new data indicate that this action at the cystine-glutamate exchanger is not required for NAC’s effects on cocaine reinstatement, but the induction of GLT-1 is. Furthermore, another compound, propentofylline, which increases glutamate GLT-1, is also effective in suppressing cocaine reinstatement. Cocaine decreases a marker of glial activity, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), in the nucleus accumbens, suggesting that deficient glial functioning and uptake of glutamate could be another target of therapeutics in cocaine addiction.

Editor’s Note: There are also glial deficits in depressed patients, so it is conceivable that NAC’s effect on GLT-1 glutamate clearance is also involved in the antidepressant effects of NAC.

NAC Normalizes Glutamate Levels in Cocaine-Dependent People

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, while GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter. Too much or too little of one or the other can lead to an imbalance in neuronal communication. In a 2012 study by Schmaal et al. published in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, cocaine-dependent patients were found to have high levels of glutamate in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. A single administration of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) at a dose of 2400mg lowered these levels.

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, while GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter. Too much or too little of one or the other can lead to an imbalance in neuronal communication. In a 2012 study by Schmaal et al. published in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, cocaine-dependent patients were found to have high levels of glutamate in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. A single administration of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) at a dose of 2400mg lowered these levels.

Healthy (non-addicted) participants who received the same administration of NAC did not show the same drop in glutamate levels.

The study also observed levels of impulsivity in the patients. Higher baseline levels of glutamate were associated with greater impulsivity, and both higher baseline level of glutamate and greater impulsivity were predictive of a larger drop in glutamate levels following NAC administration.

The researchers suggest that these findings may eventually be used in the treatment of cocaine-addicted people, since abnormal glutamate levels are related to risk of relapse. In drug-dependent rodents, NAC was found to normalize hyper-responsive glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens (the brain’s reward center) and prevent cocaine-reinstatement or relapse.

Editor’s Note: When these data from the lab of Peter Kalivas at the Medical University of South Carolina were initially collected, it was thought that NAC’s effect on a cystine-glutamate exchanger in the nucleus accumbens explained its treatment success, but new data suggest that NAC may actually facilitate glutamate clearance by increasing the number of glutamate transporters in glial cells.

Psychiatric Revolution: Changes in Behavior Are Associated with Dendritic Spine Shape and Number

New research shows that cocaine, defeat stress, the rapid-acting antidepressant ketamine, and learning and memory can change the size, shape, or number of spines on the dendrites of neurons. Dendrites conduct electrical impulses into the cell body from neighboring neurons.

Cocaine

Several researchers, including Peter Kalivas at the Medical University of South Carolina, have reported that cocaine increases the size of the spines on the dendrites of a certain kind of neurons (GABAergic medium spiny neurons) in the nucleus accumbens (the reward center in the brain). This occurs through a dopamine D1 selective mechanism. N-acetylcysteine, a drug that can be found in health food stores, decreases cocaine intake in animals and humans, and also normalizes the size of dendritic spines.

Depression

Depression in animals and humans is associated with decreases in Rac1, a protein in the dendritic spines on GABA neurons in the nucleus accumbens. Rac1 regulates actin and other molecules that alter the shape of the spines.

In an animal model of depression called defeat stress, rodents are stressed by repeatedly being placed in a larger animal’s territory. Their subsequent behavior mimics clinical depression. This kind of social defeat stress decreases Rac1 and causes spines to become thin and lose some function. Replacing Rac1 returns the spines to a more mature mushroom shape and reverses the depressive behavior of these socially defeated animals. Researcher Scott Russo has also found Rac1 deficits in the nucleus accumbens of depressed patients who committed suicide. Russo suggests that decreases in Rac1 are responsible for the manifestation of social avoidance and other depressive behaviors in the defeat stress animal model, and that finding ways to increase Rac1 in humans would be an important new target for antidepressant drug development.

Another animal model of depression called chronic intermittent stress (in which the animals are exposed to a series of unexpected stressors like sounds or mild shocks) also induces depression-like behavior and makes the dendritic spines thin and stubby. The drug ketamine, which can bring about antidepressant effects in humans in as short a time as 2 hours, rapidly reverses the depressive behavior in animals and converts the spines back to the larger, more mature mushroom-shape they typically have.

Learning and Extinction of Fear

Researcher Wenbiao Gan has reported that fear conditioning can change the number of dendritic spines. When animals hear a tone paired with an electrical shock, they begin to exhibit a fear response to the tone. In layer 5 of the prefrontal cortex, spines are eliminated when conditioned fear develops, and are reformed (near where the eliminated spines were) during extinction training, when animals hear the tones without receiving the shock and learn not to fear the tone. However, in the primary auditory cortex the changes are opposite: new spines are formed with learning, and spines are eliminated with extinction.

Editor’s Note: It appears that we have arrived at a new milestone in psychiatry. In the field of neurology, changes seen in the brains of patients with strokes or Alzheimer’s dementia have been considered “real” because cells were obviously lost or dead. Psychiatry, in comparison, has been considered a soft science because neuronal changes have been more difficult to see and illnesses were and still are called “mental.” Now that new technologies have made a deeper level of precision, observation, and analysis possible, we know that the brain’s 12 billion neurons and 4 times as many glial cells are exquisitely plastic–capable of biochemical and structural changes that can be reversed using appropriate therapeutic maneuvers.

The changes associated with abnormal behaviors, addictions, and even normal processes of learning and memory now have clearly been shown to correspond with the size, shape, and biochemistry of dendritic spines. These subtle, reproducible changes in the brain and body are amenable to therapeutic intervention, and are now even more demanding of sophisticated medical attention.